Unit 2: Open Innovation as a response to cultural heritage crises and the role of academia-society cooperation

Having explored what open innovation really entails and its value to academia-society cooperation, this unit sheds light on the role of open innovation in contexts of crisis during which cultural heritage is threatened by natural or human-driven activities. To be more precise, this unit turns its focus on cultural and natural heritage preservation efforts by international organisations and bodies, such as Blue Shield International and the Conflict and Environment Observatory. Additionally, it brings insights from cultural heritage preservation initiatives in Palmyra, Syria, that highlight the critical role of citizen engagement in situations of crisis.

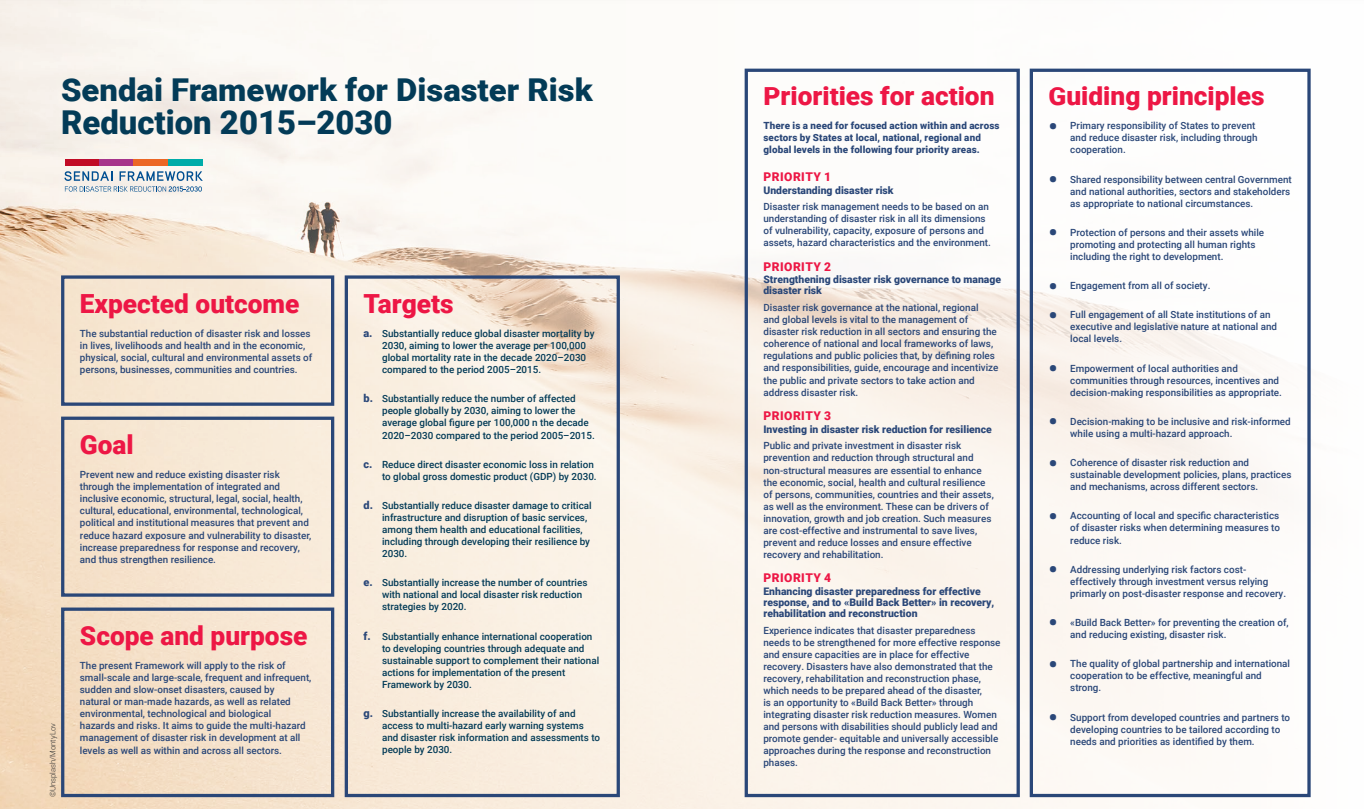

Unit 2 also looks at major international structures and frameworks that aim to monitor and minimise the loss in cultural heritage worldwide, such as the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) and the Sendai framework. Nevertheless, to generate longstanding resilient responses to crises, experts stress the need for bottom-up and participatory actions in cultural heritage preservation (see section 2.2). Eventually, the unit provides concrete examples of cultural heritage crisis response through open innovation, while it points to the need to build resilience in the cultural heritage field by adopting bottom-up and participatory open innovation practices.

2.1 Preserving cultural heritage in times of crisis

In today’s world a crisis, be it climate change, an armed conflict or any other kind of human harmful intervention may quickly become the reality for any nation. Such crises can be a threat to the existence of cultural (tangible or intangible) or/and natural heritage in the place they occur. In order to minimise this threat the international community has established special organisations and crisis response mechanisms. Let us now look at some of them to better understand how they operate and what actions they undertake to protect cultural heritage in times of crisis.

The first example is Blue Shield International which is among the most prominent international organisations.

Founded by the International Council on Archives (ICA), the International Council of Museums (ICOM), the International Federation of Library and Information Associations and Institutions (IFLA) and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), the NGO adopts the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property and implements it to cultural sites which need to be protected, so that they can be recognised by people who are responsible for their protection. Blue Shield acts as an advisory body to UNESCO in areas such as protecting cultural heritage, guaranteeing the implementation of the 1954 Hague Convention and spreading awareness, and cooperating in the field of cultural heritage protection and preservation (Blue Shield International Factsheet, November 2020).

The Stone of the Sun in the National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City https://unsplash.com/photos/-ztIx3CXXAA

Nevertheless, it is important to understand that cultural heritage is not the only heritage that needs protection and preservation. Natural heritage is also in need as it deserves to be safeguarded from any source of destruction. In fact, since 1972, UNESCO has adopted the Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (UNESCO, 1972) that enshrines the value of both cultural and natural heritages for humanity.

Environmental degradation can already be observed as a consequence of climate change, and further deterioration of natural heritage caused by armed conflicts has brought to the fore the value of biodiversity and the need for collective action to preserve it. One of the organisations whose aim is to collect and monitor data on the influence of armed conflict and its consequence on the environment is the Conflict and Environment Observatory, founded in 2018.

We have already established that natural heritage is also hit by war and conflicts, so it is not surprising that there is an urgent need to develop innovative solutions and tools that will assist scientific communities, preservation NGOs and citizens in assessing the impact of conflicts on their environment and taking action against it. Driven by this premise, the Conflict and Environmental Observatory points to the effects of war on the biodiversity of conflict-affected areas; an issue often neglected by the international community. It clearly stated in a recent article on the Conflict and Environmental Observatory website:

“Conservation in conflict settings means working in areas where national governments may have little de facto control, and where political dynamics can shift over very short time periods. However, current best practice norms largely assume that it is possible to identify who is able to give permission to NGOs to access and work in particular areas. This may not be the case in an area affected by active conflict. This then puts conservation organisations in a difficult position, for instance when collaborating with de facto power brokers to carry out their activities could lead to accusations of partisanship. If multilateral agreements addressed and clarified the role of conservation organisations during wars, this could also make it easier for conservation organisations to engage in these settings”. (Schulte to Bühne Henrike, 2022)

The Conflict and Environmental Observatory has also based its research on civilian science and citizens’ engagement in monitoring and diffusing data and useful information about the condition of natural heritage in times of crisis. Through encouraging public deliberation on the impact of conflicts on the environment, the Observatory places at the centre of its activities the generation of open and innovative solutions, tools and policy recommendations that, without the active involvement of citizens, may not monetise into concrete action.

Let us now look closer at initiatives carried out to help preserve cultural heritage in Arab countries as they may serve as another tangible example of how cultural heritage experts and ordinary citizens can work together to preserve cultural heritage sites that have been affected to various degrees by armed conflict. We will focus on the war in Syria and the illicit trade that has developed around Syrian cultural heritage assets by ISIS and other criminal networks. It has been evident to many cultural heritage experts and authorities that there is a pressing need to document, monitor and act against those involved.

In the “Culture in Crisis: Understanding the Illicit Trade under ISIS in Syria” webinar (available here), Dr Isber Sabrine, co-Founder and President of the Heritage for Peace NGO, explains how communities and civil society can be empowered through digital tools (see here an example of digital tools made for cultural heritage preservation) to fight illicit trade in countries affected by war. In this context, Dr Sabrine highlights the need to raise awareness among local communities of the value of cultural heritage protection, as well as promote a clearer and more effective legal framework on illegal excavations and illicit trade both at local and international levels. Summing up, the key takeaway of Dr Sabrine’s remarks on Heritage for Peace NGO is his conclusion on citizen engagement and its importance for cultural heritage preservation in times of crisis:

“we need to work with locals…to empower locals in documenting and tackling illicit cultural heritage trade” (Dr Sabrine Isber, 2022, June, webinar)

Ancient site of Palmyra damaged by ISIS, 2020 https://unsplash.com/photos/vi1fIqmbHP0

As the Syrian War brought international attention to the threats that Syrian cultural heritage may face, the case of the Palmyra archaeological site and the destruction of an important part of it by the Islamic State in 2015, stressed the need for a joint initiative to help protect and preserve those sites in direct collaboration with local communities. In a recent webinar under the title “Saving Palmyra” (June 23th, 2022, available here), Dr Isber Sabrine was invited to speak of the initiatives and efforts carried out so far by experts and citizens to help preserve the Palmyra site.

In his speech, Dr Sabrine outlined several projects and initiatives undertaken by NGOs, like the Palmyrene Voices initiative that has been set up by the Heritage for Peace (H4P) organisation and aims to provide a platform of communication and coordination for Palmyrene people in Syria and abroad as well as to make them co-participants in the reconstruction of Palmyra. To better understand the current context regarding the needs of the Palmyra cultural site, research was carried out on the status of the archaeological site and its management before and during the conflict, as is often the case in cultural heritage preservation efforts in conflict zones.

As the MENA region’s (Middle East and North Africa) rich cultural heritage has been severely hit by conflicts and illicit trade networks, the Arab Network of Civil Society Organizations to Safeguard Cultural Heritage (ANSCH) was launched on March 2020 (Blue Shield International, 2020) as a joint initiative of the Heritage for Peace NGO in cooperation with Arab civil society organisations. Among the key objectives of this Arab Network are the identification of cultural sites in need of protection in Arab countries as well as the empowerment of local communities towards active participation in the management of cultural heritage. This way, citizens become part of the solutions outlined by cultural heritage experts, while cultural heritage protection and preservation become a matter of collective consideration and community engagement, thus creating a more sustainable and long-lasting impact on the cultural heritage sector of the affected territory.

You can find more information about the ANSCH initiative here.

Reflection questions:

-

Consider the example of The Conflict and Environmental Observatory and Heritage for Peace NGO, and explain why it is so important to engage citizens in heritage (cultural and natural) preservation actions. Would you like to participate in such an action?

-

Once you have watched the webinar by Dr Sabrine, explain how communities and civil society can be empowered through digital tools to fight illicit trade in countries affected by war. What are those tools?

Note down your answers in the reflective diary.

2.2 Cultural heritage under threat and open innovation: policies and methods

As we have already discussed, cultural heritage is being affected by the adverse factors of anthropogenic threats with climate change and natural disasters becoming ever more commonplace. According to the Global Assessment Report (GAR) on Disaster Risk Reduction, loss in cultural heritage assets is mainly associated with “intangible” losses (i.e., artistic and historical value) and often indirect losses (UNDRR 2019). The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) has reported over 7,000 major disaster events between 2000-2019 which resulted in the loss of over 1 million lives, about 60 thousand every year, affecting 4.2 billion people. Only in 2019, the recorded disasters brought over 100 billion in economic loss (UNDRR 2019). While the statistics are sobering, they cannot fully convey the severe negative impacts on humans, nature and the planet. Cultural heritage, both in its tangible and intangible forms, is increasingly being affected by encroachment and environmental degradation among other issues, caused by human impact, including military operations. In addition, many painful and destructive episodes related to the internment of a political, civil and warlike nature have resulted in sites of shame and cruelty, connected to what is known as difficult or “dark” heritage (Thomas et al. 2019), such as the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp and heritage memorial sites, such as the Hiroshima Peace Memorial.

The socioeconomic value of cultural heritage and its contribution to sustainable development and welfare has been ratified by international strategies and policies, initiated by UNESCO’s “Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage” (UNESCO 1972). The word ‘disaster’ has been defined by the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR) as “a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society at any scale due to the hazardous events interacting with conditions of exposure, vulnerability and capacity, leading to one or more of the following: human, material, economic and environmental losses and impacts” (UNISDR 2009).

Building capacity, managing and strengthening resilience against disaster risks for cultural heritage have been addressed through standard-setting publications such as the World Heritage Resource Manual Series (UNESCO, 2010-2022) by the three Advisory Bodies of the World Heritage Convention (ICCROM, ICOMOS and IUCN) and the UNESCO World Heritage Centre, providing focused guidance on the implementation of UNESCO’s World Heritage Convention. Additional key publications on disaster risk management with references to cultural heritage include the Conference proceedings of the 5th Session of the Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction (Global Platform 2017), the international conference “Cultural Heritage: Disaster Preparedness, Response and Recovery” by the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM 2016), training courses such as the annual International Training Course (ICT) on Disaster Risk Management of Cultural Heritage (UNESCO 2022), and strategies such as the Strategy for Reducing Risks from Disasters at World Heritage properties (UNESCO 2007). These work towards the harmonisation of actions and efficient timely responses on disaster risk management on a local and international level and include innovative elements.

https://www.undrr.org/publication/undrr-annual-report-2019

The prominent Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction has been adopted by the UN Member States with the aim of achieving a reduction in losses from natural and man-made hazards (UNISDR 2015). The agreement marks an important shift towards a people-centred approach, focusing on disaster risk management (previously disaster management) while acknowledging in explicit terms the value of integrating innovation as well as traditional, Indigenous and local knowledge and practices in DRR policy and strategy development. It is worth noting that World Heritage sites didn’t have an established policy plan for risk management against disasters (UNESCO 2015). The prominent Sendai Framework provides a solid foundation for Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) policies, which includes several references to culture and heritage, unlike preceding policy papers, revolving around the key pillars of a) understanding disaster risk, b) strengthening disaster risk governance, c) investing in disaster risk reduction for resilience and d) enhancing disaster preparedness for effective response through recovery, rehabilitation and reconstruction (UNISDR 2015).

In particular, the Sendai Agreement presents intangible cultural heritage as an invaluable source of knowledge, practices and experiences for effective contribution to threats and urgent situations, such as for achieving ecological and social sustainability, resilience and peacebuilding. Intangible cultural heritage in this context increases the capacity for open innovation by harnessing local community-based knowledge and shared skills, and by facilitating interdisciplinary partnerships across diverse actors that can foster entrepreneurship. Cultural heritage, cooperation and innovation are addressed throughout the Sendai Framework, which aims at “the substantial reduction of disaster risk and losses in lives, livelihoods and health and in the economic, physical, social, cultural and environmental assets of persons, businesses, communities and countries” (UNISDR 2015). Cultural resilience, cultural heritage protection and transboundary cooperation in global partnership settings are high on the agenda; the means to implement them outline open innovative approaches: “[…] to finance, environmentally sound technology, science and inclusive innovation, as well as knowledge and information-sharing through existing mechanisms, namely bilateral, regional and multilateral collaborative arrangements […]”, and “promote the use and expansion of thematic platforms of cooperation, such as global technology pools and global systems to share know-how, innovation and research and ensure access to technology and information on disaster risk reduction” (UNISDR 2015).

In the prominent European Expert Network for Culture (EENC) Paper (Sacco 2011), Pier Luigi Sacco introduced the concept of active cultural participation as a mainspring for open innovation and co-creation. Shifting from past frameworks of cultural production seen in Culture 1.0 and Culture 2.0, which reserved limited access to production technologies, Culture 3.0 brings a rethinking of cultural policy acting as a catalyst for sustainable development and transformation of cultural production through participation, moving away from institutional patronage towards highly coordinated communities of practice, defined as ‘massively parallel forms of collective intelligence’ (Kittur & Kraut 2008, Golub & Jackson 2010). The 8-tier approach for cultural participation by Sacco maps innovation as the first area regarding the spillover effects of culture, while other tiers include lifelong learning, new entrepreneurship models and welfare. Active cultural participation aims to achieve and strengthen the societal dimension in open innovation systems (the network of social, economic and technological actors and infrastructures) within the cultural heritage sector and beyond, where “massive bottom-up capability building” is recognised as “the most effective route to the creation of an innovation-driven economy and society” (Phelps 2013). Cultural heritage is thus recognised as a decisive part of development strategies towards open innovation in socially critical areas, fueled by the strong social incentives of participating individuals supported by active cultural participation in socio-political contexts (Sacco et al. 2018).

Reflection question: What do you remember about intangible cultural heritage and why, in your opinion, does the Sendai Agreement present it as an invaluable source of knowledge? Note down your answer in the reflective diary.

2.3 Examples of crisis response through open innovation for cultural heritage

Having covered the most important theoretical aspects of cultural heritage and the threats it is facing, let us now have a closer look at some practical examples of digitally empowered and open innovation projects developed as 1) cultural-technology solutions with the capacity to be used in hazardous situations of socio-political nature and 2) crisis response initiatives in situations where natural and cultural heritage is under threat.

In particular:

Community Networks

ICT-enabled local or community networks can be critically applied within the scope of socio-political situations and cultural-technological settings in contexts of interdisciplinary humanities. Community networks are networks that can be formed in the absence of an internet connection or outside of the web, forming transient – off the internet – community knowledge-sharing wireless networks within an area of physical proximity. Community networking initiatives, such as Piratebox and Librarybox, have been using open-source applications based on technical components that are “minimal” by eliminating functionalities to a basic level of a user-friendly, simple function yet aiming for sustainable performance, based on “minimal computing principles” (Ziku et al. 2020, Gil 2015, Sayers 2016). Community networks create pop-up local wi-fi zones independent of the internet, that enable digital interactions of communities within a low physical proximity coverage range. Their open innovation character is enhanced by the openly shared guidelines, designs, installation scripts and free/libre/open-source software (FLOSS) applications that can facilitate hybrid, virtual and physical interactions. This technology can be useful in settings that need human rights protection, achieving freedom, equal rights participation and the rights to privacy, in situations where they are increasingly threatened online. Community networks can create a shield during political crises where systems of control, such as censorship and surveillance of online citizen communications, are applied by governments in alliance with telecom providers, often operating outside the rule of law (Antoniadis 2018).

Reflection question: Think about the area where you live. Do you think that a project like the Mazi Zone could be conducted in your neighbourhood? Why / Why not? Note down your answer in the reflective diary.

2.4 Building cultural resilience through sustainable and responsible innovation

The recognition of cultural heritage as a powerful factor for strengthening social resilience and sustainable development for disaster risk management has been affirmed through several policies and agreements, including white papers, manuals, expert group reviews and more. Many of these papers, tools and practices have been developed in order to tackle disaster losses to cultural heritage and related assets, relying on local and Indigenous knowledge. In addition, the value of establishing cultural measures that are informed by local and traditional knowledge for threatening situations is becoming more widely recognised. However, there are still few options in actively engaging Indigenous people and communities of practice who are holders of traditional knowledge in disaster risk management (Dolcemascolo, 2017).

As described within the review of the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), resilience is understood as “the capacity of a system, community or society potentially exposed to hazards to adapt, by resisting or changing in order to reach and maintain an acceptable level of functioning and structure. It is determined by the degree to which the social system is capable of organising itself to increase its capacity for learning from past disasters for better future protection and to improve risk reduction measures.” (Dekens 2007). ICIMOD’s report on “Local Knowledge and Disaster Preparedness” (Dekens 2007) created a comprehensive map for a better understanding of the value of local or Indigenous knowledge and its rediscovery in disaster management and preparedness. Although any reference to innovation is missing from the review, it strives to encourage knowledge-sharing, sharing the means to production and attempting an early map of participatory and bottom-up approaches in the form of “citizen science”, “community-based and adaptive management”, among others, outlining, in essence, the building blocks for open innovation.

Furthermore, gender and vulnerability aspects in disaster risk governance are key dimensions in strengthening resilience and sustainability for the protection of cultural heritage. Translating a non-binding instrument (such as the Sendai Framework) into national governance legal frameworks may be a crucial move in this direction. Disaster risk reduction requires a multi-action system, where broad participation can be supported through inclusive governance and a people-centred approach, ensuring the adaptation not only of environmental-mindful strategies but also gender-responsive ones, on international, national and local levels.

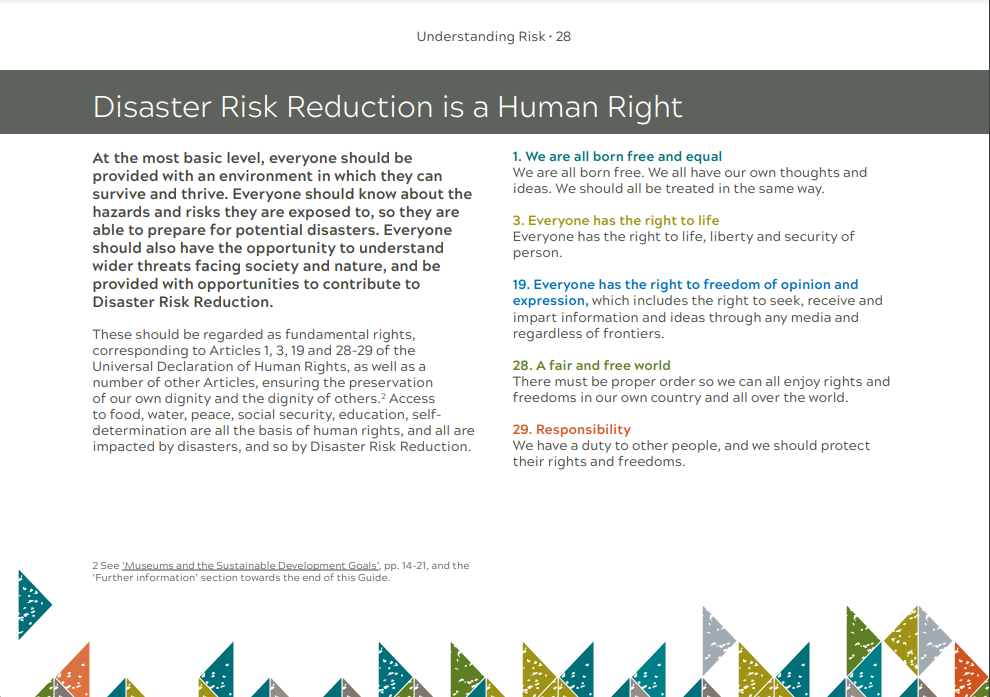

Building on the work of the Sendai Framework, Curating Tomorrow (UK) published a guide under the title “Museums and Disaster Risk Reduction” (McGhie 2020) aimed at informing people working in the cultural sector on how to integrate Disaster Risk Reduction mechanisms and strategies in their cultural institutions. What stands out in this guide is the collection of case studies that gather examples of Disaster Risk Reduction in practice throughout the world.

For the purpose of this module, it is relevant to mention the citizen science dimension which is present in one of the case studies. In particular, the guide outlines the benefits citizen science projects bring to the establishment of solid Disaster Risk Reduction mechanisms as proved by a recent study entitled “Global Mapping of Citizen Science Projects for Disaster Risk Reduction (Hicks et al. 2020). Based on this study, it has been demonstrated that citizen science projects can provide (and be):

-

Active benefits for all participants

-

Clear attempts to ensure legacy and longevity

-

Responsible engagement in both quiet times and during active hazard moments

-

Framed around DRR goals

-

Careful definition of partners (to ensure equitable outcomes)

-

Equitable and empowering.

Check more on this guide on Disaster Risk Reductionhere.

Reflection questions:

-

Define the word resilience in the context of cultural heritage in your own words. How do you understand this term?

-

How can citizen science contribute to the establishment of Disaster Risk Reduction?

Note down your answer in the reflective diary.

2.5 Critical view of innovation crisis solutions for cultural heritage

The search for the origin of crises, hazards and disasters as well as the effectiveness of their management mechanisms have been critically examined within the social sciences and humanities, to the degree that the belief in “development as progress” may be deemed unsustainable (Sachs, 2010). The concept of development as a solution to global crises has long been criticised; in this perspective, the current economic system and its market forces are held accountable for the issues which it strives to solve. In “Pluriverse: A post-development dictionary” by Kothari et al. (2019), the belief in the concept of development is critically viewed as unsustainable and the modernist ontology is challenged on the basis of alternative, more ethical and decolonial practices (Kothari et al., 2019). The catchwords of this approach are “degrowth”, “commons” and “post-development”, among others. Calling for a reassessment of the concept of development and suggesting the counter term “post-development”, the critical approach aims to set up a transdisciplinary understanding of cultural practices, in their broader socio-political, economic and ecological dimension (Demaria & Kothari, 2017).

In this perspective, innovation models that are promoted as “crisis solutions” are examined and often criticised as environmentally wasteful and foremost profit-driven. In order to achieve sustainability, it is crucial that local knowledge, indigenous and community-based cultural practices remain as open knowledge, safe in the realms of the commons. Kothari focuses on the staggering crisis manifestations, aiming to dismantle the rhetoric of unsustainable forms of governance in cultural, social and environmental settings; innovation is complemented with “social” and “civic” innovation, responsible participation and collective ethics.

Unit 2 Quiz:

The next unit of our module presents real-life examples of different initiatives undertaken by different organisations or people in the horrid time of the war. Unit 3 presents a case study of the impact the war has on Ukraine’s cultural heritage. Please remember to have your reflective diary at hand to note your thoughts and answers to reflection questions which, as you already know, are posted in different places in the unit. As previously explained, this diary will enrich your educational journey and will become an invaluable resource for the future for you to refer back to what you have learnt throughout the whole module.

Further readings:

- UNESCO (1972, November 16). Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. https://www.refworld.org/docid/4042287a4.html

- Blue Shield International, (November 19, 2020), About the Blue Shield: Factsheet, https://theblueshield.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/Blue-Shield_International-Fact-Sheet-May-2021.pdf

- Blue Shield International. (March 19, 2020), BSI attends launch of Arab CH Safeguarding Network, https://theblueshield.org/bsi-attends-launch-of-arab-ch-safeguarding-network/

- Schulte to Bühne, H. (2022), Do mention the war: Why conservation NGOs must speak out on biodiversity and conflicts, The Conflict and Environment Observatory, https://ceobs.org/do-mention-the-war-why-conservation-ngos-must-speak-out-on-biodiversity-and-conflicts/

- Abraham Path Initiative. (June 2020), Saving Palmyra, Webinar, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s8Z6BXAHK20

- Antoniadis, P. (2018). The Organic Internet: Building Communications Networks from the Grassroots. In: Giorgino, V., Walsh, Z. (eds) Co-Designing Economies in Transition. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-66592-4_13

- Council of Europe. (May 20, 2022), Recommendation CM/Rec(2022)15 of the Committee of Ministers to member States on the role of culture, cultural heritage and landscape in helping to address global challenges, https://search.coe.int/cm/Pages/result_details.aspx?ObjectId=0900001680a67952

- Ziku, M., Leventaki, E., Brailas, A., Maglavera, S. & Mavridis, J. (2020). MAZI means together: An open-source “minimal computing” local network infrastructure used for cultural event organisation, fieldwork research and community-based curation. Digital Humanities 2020 carrefours/intersections. Ottawa, Canada. http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/81p5-t144

- Thomas, S., Herva, VP., Seitsonen, O., Koskinen-Koivisto, E. (2019). Dark Heritage. In: Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51726-1_3197-1

- UNDRR (2019). Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction. Geneva, Switzerland. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. https://www.undrr.org/publication/global-assessment-report-disaster-risk-reduction-2019

- UNESCO (2007). Convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage. Christchurch, New Zealand. https://whc.unesco.org/archive/2007/whc07-31com-72e.pdf

- UNESCO (2010-2022), World Heritage Resource Manual Series. https://whc.unesco.org/en/resourcemanuals/

- UNESCO (2015). Reducing Disasters Risks at World Heritage Properties. https://whc.unesco.org/en/disaster-risk-reduction/

- UNESCO (2022). International Training Course (ICT) on Disaster Risk Management of Cultural Heritage 2022. https://rdmuch-itc.com/itc/itc-2022-call-for-applications/

- UNISDR (2009). Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction. United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction.

- UNISDR (2015). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015 – 2030. World Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction. Sendai, Japan. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/793460#

- Culture in crisis, (June 2020), Culture in Crisis: Understanding the Illicit Trade under ISIS in Syria, Webinar, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4cjvmjff7OU

- Dekens, J. (2007). Local Knowledge for Disaster Preparedness: A literature Review. International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD). Kathmandu, Nepal. https://doi.org/10.53055/ICIMOD.474

- Demaria, F. & Kothari, A. (2017). The Post-Development Dictionary agenda: paths to the pluriverse, Third World Quarterly, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1350821

- Dolcemascolo, G. (2017). Cultural Heritage and Indigenous Knowledge for Building Resilience. 2017 Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction.United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR). https://www.unisdr.org/conferences/2017/globalplatform/en/programme/working-sessions/view/597.html

- Gil, A. (2015). The User, the Learner and the Machines We Make. Minimal Computing: A Working Group of GO::DH. http://go-dh.github.io/mincomp/thoughts/2015/05/21/user-vs-learner

- Global Platform (2017). The Fifth Session of the Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction. UNDRR. http://unisdr.org/go/gp2017/proceedings

- Golub, B. & Jackson, M. O. (2010). Naïve Learning in Social Networks and the Wisdom of Crowds. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 2 (1): 112-49. https://doi.org/10.1145/1460563.1460572

- Hicks, A., Barclay, J., Chilvers, J., Armijos, M. T., Oven, K., Simmons, P. & Haklay, M. (2019). Global Mapping of Citizen Science Projects for Disaster Risk Reduction. Front. Earth Sci. 7:226. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2019.00226

- ICCROM (2016, November 3-4). Cultural Heritage: Disaster Preparedness, Response and Recovery [conference]. Lisbon, Portugal.

- Kittur, A. & Kraut, R. E. (2008). Harnessing the wisdom of crowds in wikipedia: quality through coordination. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW. 37-46. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, USA. https://doi.org/10.1145/1460563.1460572

- Kothari, A., Salleh, A., Escobar, A., Demaria, F. and Acosta Alberto (eds) (2019) Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary. Delhi, India: Authors Up Front / Tulika / Columbia University Press.

- Mazi Zone http://www.mazizone.eu

- McGhie, H.A. (2020). Museums and Disaster Risk Reduction: building resilience in museums, society and nature. Curating Tomorrow, UK.

- Phelps, E. (2013). Mass Flourishing. How Grassroots Innovation Created Jobs, Challenge, and Change; Princeton University. Press: Princeton, NJ, USA.

- Resilient Reefs https://www.barrierreef.org/what-we-do/projects/resilient-reefs

- Sacco, P., Ferilli, G., & Tavano Blessi, G. (2018). From Culture 1.0 to Culture 3.0: Three Socio-Technical Regimes of Social and Economic Value Creation through Culture, and Their Impact on European Cohesion Policies. Sustainability, 10(11), 3923. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10113923

- Sacco, P.L., (2011) Culture 3.0: A new perspective for the EU 2014 – 2020 structural funding programming, European Expert Network on Culture (EENC).

- Sachs, W. (ed.) (2010 [1992]), The Development Dictionary: A Guide to Knowledge as Power. London: Zed Books.

- Sayers, G. (2016). Minimal Definitions, Minimal Computing: A Working Group of GO::DH. https://go-dh.github.io/mincomp/thoughts/2016/10/02/minimal-definitions