- Home

- Study book

- Week 1: Introduction to multilingualism and plurilingualism

- Week 2: Understanding bilingualism

- Week 3: Multilingualism in state and society, and the role of communities

- Week 4: Early Childhood Multilingualism

- Week 5: Multilingual school

- Week 6: Multilingual higher education

- Week 7: Interculturalism and intercultural communication

- Course team

MOOC: Multilingual Education

Week 3 Pool of ideas for seminars, multilingualism and society

The readings, videos and activities below are designed to provide opportunities for deepening your knowledge about the topics covered in Week 3 of the MOOC (e-Course) on the topic of “Multilingualism and Society”. It is aimed to be used in academic seminars, providing extra materials, some suggestions for activities etc.

In order to become familiar with the basics of the topic, it is recommended that you go through the self-study e-Course as follows:

- To get generally acquainted with the topic and terms of multilingualism in state and society, study the MOOC materials of Week 3 part 1 here: https://sisu.ut.ee/multilingual/book/1-language-policies-and-multilingualism-terms-population-0

- Week 3 part 2 here: https://sisu.ut.ee/multilingual/book/2-languages-within-society

- Week 3 part 3 here: https://sisu.ut.ee/multilingual/book/3-language-planning

- Complete the Week 1 quiz here: https://sisu.ut.ee/multilingual/multilingual-quiz-3

Extra materials for academic seminars or for individual learners to deepen their understanding of the topic:

3.1 Language environment and linguistic landscape

Sociolinguistic context includes linguistic landscapes – known as LL – that is any display or exposure of language(s) in public spaces for various functional and symbolic purposes. LL may include audial and graphic signs, both material and virtual elements.

- further deeper familiarisation with the issue.

Read Cenoz, J. & Gorter. D. 2008. Linguistic landscape and minority languages. International Journal of Multilingualism. 3 (1). https://doi.org/10.1080/14790710608668386

This paper focuses on the linguistic landscape of two streets in two multilingual cities in Friesland (Netherlands) and the Basque Country (Spain) where a minority language is spoken, Basque or Frisian. The paper analyses the use of the minority language (Basque or Frisian), the state language (Spanish or Dutch) and English as an international language on language signs. It compares the use of these languages as related to the differences in language policy regarding the minority language in these two settings and to the spread of English in Europe. The data include over 975 pictures of language signs that were analysed so as to determine the number of languages used, the languages on the signs and the characteristics of bilingual and multilingual signs. The findings indicate that the linguistic landscape is related to the official language policy regarding minority languages and that there are important differences between the two settings.

- Ben-Rafael, E.; Shohamy, E; Amara, M.H; Trumper-Hecht, N. 2006. Linguistic Lanscape as Symbolic Construction of the Public Space: The Case of Israel. International Journal of Multilingualism. 3 (1). https://doi.org/10.1080/14790710608668383

Linguistic landscape (LL) refers to linguistic objects that mark the public space. This paper compares patterns of LL in a variety of homogeneous and mixed Israeli cities, and in East Jerusalem. The groups studied were Israeli Jews, Palestinian Israelis and non-Israeli Palestinians from East Jerusalem, of whom most are not Israeli citizens. The study focused on the degree of visibility on private and public signs of the three major languages of Israel-Hebrew, Arabic and English. This study reveals essentially different LL patterns in Israel’s various communities: Hebrew–English signs prevail in Jewish communities; Arabic Hebrew in Israeli–Palestinian communities; Arabic–English in East Jerusalem. Further analyses also evince significant – and different – discrepancies between public and private signs in the localities investigated. All in all, LL items are not faithfully representative of the linguistic repertoire typical of Israel’s ethnolinguistic diversity, but rather of those linguistic resources that individuals and institutions make use of in the public sphere. It is in this perspective that we speak of LL in terms of symbolic construction of the public space which we explain by context-dependent differential impacts of three different factors – rational considerations focusing on the signs’ expected attractiveness to the public and clients; aspirations of actors to give expression to their identity through their choice of patterns that, in one way or another, represent their presentation of self to the public; and power relations that eventually exist behind choices of patterns where sociopolitical forces share relevant incompatible interests.

- application of the knowledge using the local or familiar context or in-class discussion.

Exercise: map the linguistic landscape (LL). In this exercise students will be assigned with the task to map the linguistic landscape of a specific environment – their school, neighborhood, community etc. The tasks includes mapping in various domains:

- Audial landscape: which languages are heard? Which ones are meaningful for the student (the ones he/she understands) and which ones are “noise” (do not understand) and do not therefore classify as audial signs.

- Graphic landscape: which ones are he/she student to read and understand and which ones not (if they appear in the observed environment)?

- The landscapes should be further categorized as material or virtual.

Discuss in the class the student reports on language environment mapping: which landscapes were appearing in a specific environment? What are the drivers – personal and social – for such landscapes?

Exercise: design language study using the environment. Students design the study process for learning the languages through the use of the existing language environment based on the mapped language landscape. The aim of this seminar activity is to acknowledge, how every educator could take advantage of the surroundings for better and more meaningful language acquisition. For example, taking the learners outside to town could be turned into a useful language learning experience by preparing certain tasks for it, e.g. a booklet with a variety of tasks, questions, which would draw learners’ attention to the languages that are present in different domains in the given environment (street names, information boards and street signs, advertisement, car stickers, T-shirts etc.).

3.2 Language status

- further deeper familiarisation with the issue.

Ethnologue web portal provides a summarized information regarding different levels of language status using EGID scale. Students should read the text, paying special attention to the tables where language status grades are defined. Further the scale of levels from 1 (strong) to 10 (weak) is explained. There is further the categorization of official recognition of language status (Table 3). Read the first page of the referred web source.

- application of the knowledge using the local or familiar context or in-class discussion.

Exercise: Using information provided in Ethnologue, students are be asked to analyse a language or languages in specific context (international, national, regional, local, community) based on the scale and based on the official recognition categories. For example, in case of South Tyrol (Italy) scale the languages used in the region based on EGID scale. Then, analyse the categories of official recognition given the each of the languages in South Tyrol.

- Discuss in the class the criteria which is used for scaling and categorization.

- Discuss the contextual and historic factors impacting the scaling and the categorisation.

3.3 Language conflict and planning

In this section teachers can focus on language conflict, language policy, language shift or language planning or equally on all those.

Language conflict and policy

- further deeper familiarisation with the issue.

Read Spolsky, B. 2007. Towards a Theory of Language Policy. Working Papers on Educational Linguistics 22/1. https://wpel.gse.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/archives/v22/v22n1_Spolsky.pdf

This paper, developed as a result of that given at the 2006 Nessa Wolfson Memorial colloquium, presents the beginning of a theory of language policy and management. Essential features are the division into domains (standing for the speech communities to which the policy is relevant); recognition of language policy as involving practices, beliefs and management; and a consideration of internal and external influence on policy in the domain. The paper looks briefly at some domains and concludes with an analysis of school and the complexity of understanding language education policy

- application of the knowledge using the local or familiar context or in-class discussion.

Exercise: based on the reading, ask students to prepare an essay on the language conflict/security in their own country /region. In class discussion: What are the vices and virtues of an efficient/non-efficient language policy?

- How would you describe your own country in the framework of territorial / social / virtual language security?

- Which groups are antagonised?

- Are there any tensions or language conflicts?

- Are there any differing values, competing for the same resources, pushing towards alternative goals?

Language planning

- further deeper familiarisation with the issue.

Read Ruiz, R. 1984. Orientations in Language Planning. NABE Journal 8 (2). https://doi.org/10.1080/08855072.1984.10668464

Basic orientations toward language and its role in society influence the nature of language planning efforts in any particular context. Three such orientations are proposed in this paper language-as-problem, language-as-right, and language-as-resource. The first two currently compete for predominance in the international literature. While problem-solving has been the main activity of language planners from early on (language planning being an early and important aspect of social planning in ‘development’ contexts), rights-affirmation has gained in importance with the renewed emphasis on the protection of minority groups. The third orientation has received much less attention; it is proposed as vital to the interest of language planning in the United States.

Bilingual education is considered in the framework of these orientations. Many of the problems of bilingual education programs in the United States arise because of the hostility and divisiveness inherent in the problem- and rights-orientations which generally underlie them. The development and elaboration of a language-resource orientation is seen as important for the integration of bilingual education into a responsible language policy for the United States.

- application of the knowledge using the local or familiar context or in-class discussion.

Exercise: based on the reading, analyse the language planning in education in your country considering the following questions:

- What is the approach to language planning in education in your country: language-as-problem, language-as-right or language-as-resource? Provide evidence for your argument.

Teachers can develop normative debate in the class: which of the language planning orientations is more beneficial for multilingual societies? Pro and contra arguments. The option is also to divide students randomly in “pro” and “contra” groups for the discussion “Language-as-right planning approach in education benefits all”.

Exercise: Assign students with the task to develop a research project analyzing language planning activities in his/her country. Find out basic facts about language planning activities, map and analyse in the project. Present them in the seminar.

-

Status planning: How is language choice and use regulated? What are the main legal acts dealing with language planning? Which main international human rights instruments providing linguistic rights has your country adhered to (ratified / signed)?

Do some other (minority) languages enjoy language rights and recognition? - Corpus planning: How is your national language standard fixed, what institution is in charge of it? What organisation elaborates terminology? How are personal, geographical and business names fixed and regulated?

-

Language education planning: How are languages arranged in your national curriculum?

What are the outcome levels? In what languages do the general public schools / private schools operate? - Language technology: How is the HLT development regulated and supported in your country (national programmes, tenders, etc.?

Language shift

-

- further deeper familiarisation with the issue.

Language shift has occurred in some instances and it is not a universal phenomena. In this section of the class, students can familiarize themselves with various case studies and in-class discussion can be conducted based on the knowledge acquired from the reading.

Read Kandler, A.; Unger, R.; Steele, J. 2010. Language shift, bilingualism and the future of Britain’s Celtic languages. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0051

‘Language shift’ is the process whereby members of a community in which more than one language is spoken abandon their original vernacular language in favour of another. The historical shifts to English by Celtic language speakers of Britain and Ireland are particularly well-studied examples for which good census data exist for the most recent 100–120 years in many areas where Celtic languages were once the prevailing vernaculars. We model the dynamics of language shift as a competition process in which the numbers of speakers of each language (both monolingual and bilingual) vary as a function both of internal recruitment (as the net outcome of birth, death, immigration and emigration rates of native speakers), and of gains and losses owing to language shift. We examine two models: a basic model in which bilingualism is simply the transitional state for households moving between alternative monolingual states, and a diglossia model in which there is an additional demand for the endangered language as the preferred medium of communication in some restricted sociolinguistic domain, superimposed on the basic shift dynamics. Fitting our models to census data, we successfully reproduce the demographic trajectories of both languages over the past century. We estimate the rates of recruitment of new Scottish Gaelic speakers that would be required each year (for instance, through school education) to counteract the ‘natural wastage’ as households with one or more Gaelic speakers fail to transmit the language to the next generation informally, for different rates of loss during informal intergenerational transmission.

-

- application of the knowledge using the local or familiar context or in-class discussion.

Exercise: Suggestions for the discussion in contact seminars:

- What does ‘language shift’ mean? How does it affect Celtic languages?

- What do the demographic trajectories of the studied languages show?

- Are there any other situations that you are aware of in which the languages in the community are shifting?

- Is it more like a inevitable process or something that people can have a say in it? What could/should be done about it?

Language diversity and language status seminar

The seminar will help you to understand what language status means, and how it may change.

Reading materials:

EN Language Status. Ethnologue- Languages of the World at https://www.ethnologue.com/about/language-status

Linguistic diversity: the heart of Europe’s DNA, https://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-14-492_en.htm

Vices and virtues of an efficient or non-efficient language policy

Suggested to be used for the dicsussion:

Brainstorming: What might be vices and virtues of an efficient or vice versa, non-efficient language policy?

- How would you describe your own country / neighbouring countries in the framework of territorial / social / virtual security?

- Which groups are antagonised?

- Are there any tensions or conflicts?

- Are there any differing values, competing for the same resources, pushing towards alternative goals?

Reading – Spolsky, Bernard “Towards a Theory of Language Policy” https://wpel.gse.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/archives/v22/v22n1_Spolsky.pdf

Is our society monoglossic or heteroglossic?

https://heteroglossia.net/Home.2.0.html

This webpage proposes a variety of reading materials on research, projects and information on multilingualism in English (EN) or German (DE).

The reading task for the contact seminar could ask students to find enough information about monoglossia and heteroglossia to be able to identify the tendency in their own society (policy, educational practice etc.).

Discussion questions:

- Why do some societies tend to implement monoglossic ideology and why others promote heteroglossic ideology?

- What are the options a government could do about the education either directing towards monoglossia or heteroglossia? What are the reasons behind those choices?

Language shift, bilingualism and the future of Britain’s Celtic languages

Anne Kandler, Roman Unger and James Steele (2010). Language shift, bilingualism and the future of Britain’s Celtic languages. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0051

The article may have access restrictions, but should be available for academic purposes for the universities via their database access!

Suggestions for the discussion in contact seminars:

- What does ‘language shift’ mean? How does it affect Celtic languages?

- What do the the demographic trajectories of the studied languages show?

- Are there any other situations that you are aware of in which the languages in the community are shifting?

- Is it more like a inevitable process or something that people can have a say in it? What could/should be done about it?

Families as primary socialization agents- a real-life example

According to the social identity theory, language is one of the most important means by which people identify themselves and others. Language is seen as an important marker of differences or boundaries between different groups, i.e. people could be categorized as “speaker of language X”. The formation of one’s identity and the socialization as such typically takes place in the family, where the shared beliefs, values and behaviours is mediated through parents or other significant members of the family, and here language is one of the most important means of value acquisition, an integrated and inseparable part of this process (Byram, 2008).

Here is one real-life story about how one’s family may work as one most important socialization agent related to child’s attitude towards languages.

The article is located in the pages 6-9 and in three languages:

EE Keelest ja keeltest, Marina Kaljurand, Eesti vabariigi välisminister

EN About Language and Languages, Marina Kaljurand, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Estonia

RU О языке и языках, Марина Кальюранд, Министр иностранных дел Эстонской республики

Empirical research task: Language planning activities in my country

Find out basic facts about language planning activities in your country. Present them in the seminar.

-

Status planning: How is language choice and use regulated?

What are the main legal acts dealing with language planning?

Which main international human rights instruments providing linguistic rights has your country adhered to (ratified / signed)?

Do some other (minority) languages enjoy language rights and recognition? -

Corpus planning: How is your national language standard fixed, what institution is in charge of it?

What organisation elaborates terminology?

How are personal, geographical and business names fixed and regulated? -

Language education planning: How are languages arranged in your national curriculum?

What are the outcome levels?

In what languages do the general public schools / private schools operate? - Language technology: How is the HLT development regulated and supported in your country (national programmes, tenders, etc.?

Articles that encourage parents to start “investing” into their child development with just exposing their child to another language, 1 hour a day (music, cartoons etc)

http://www.multilingualliving.com/2010/09/07/bilingual-children-with-one-hour-of-language-a-day-part-one/

http://www.multilingualliving.com/2010/09/8/bilingual-children-with-one-hour-of-language-a-day-part-two/

Links between language policy and assessment in multilingual contexts

Durk Gorter & Jasone Cenoz (2017) Language education policy and multilingual assessment, Language and Education, 31:3, 231-248, DOI: 10.1080/09500782.2016.1261892 , https://www.tandfonline.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1080%2F09500782.2016.1261892

This Open Access article presents the direct links between language policy and assessment in multilingual contexts. The authros illustrate the bi-directional relationship with the examples of the USA, Canada, and the Basque Country. The changing views about the use of languages in education are shifting.

“The shift from language isolation policies in language teaching and assessment towards more holistic approaches that consider language-as-resource and promote the use of the whole linguistic repertoire. However, the implementation of programs based on holistic approaches is limited and application in language assessment modest. Traditions and monolingual ideologies do not give way easily. We show some examples of creative new ways to develop multilingual competence and cross-lingual skills. The assessment of interventions with a multilingual focus point to a potential increase in learning outcomes. Multilingualism is a point of departure because in today’s schools, students who speak different languages share the same class, while at the same time learning English (and other languages). We conclude that holistic approaches in language education policy and multilingual assessment need to substitute more traditional approaches.” (Gorter & Cenoz, 2017)

Language policy to help people acquire the language of the society

Every child and “adult should have the right to learn the official language of his/her country of residence to the level of academic fluency. Authorities should remove any major obstacles; for example, by providing free additional support.

‘Migrant,’ ‘Immigrant,’ ‘Community’ languages should be explicitly recognised through appropriate instruments at European level. They should be eligible for more funding

support in national and European policies. The offer of languages other than the national language(s) should be adapted so that all students, regardless of their background,

have the opportunity to learn the languages of their community, from pre-primary to university education.” (Multilingualism For Stable And Prosperous Societies. Language Rich Europe Review and Recommendations)

Read more here: Multilingualism For Stable And Prosperous Societies. Language Rich Europe Review and Recommendations, https://www.britishcouncil.nl/sites/default/files/lre_review_and_recommendations.pdf

Questions for discussion:

– How is my country providing the necessary support for learning the language of my country for the people whose home language is different from that?

– What could be done better?

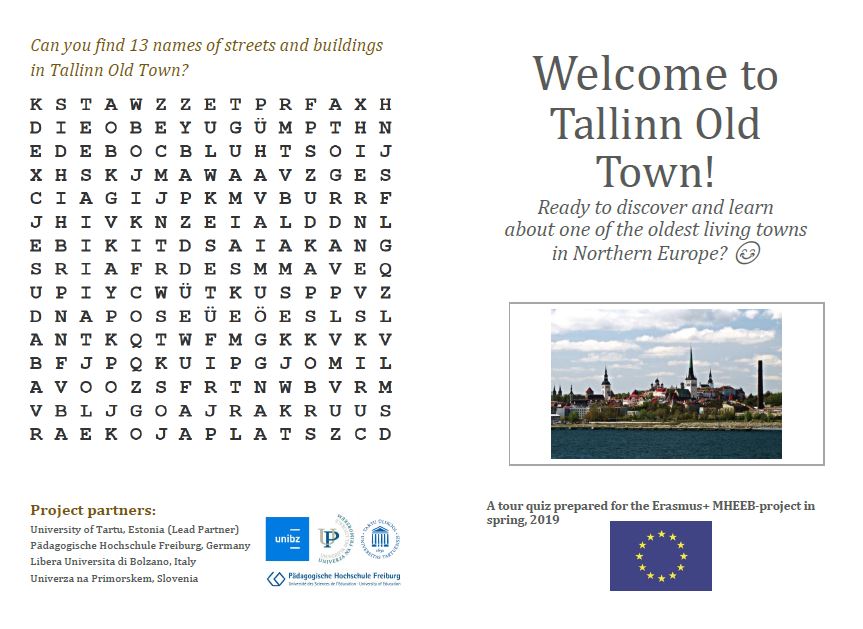

Languages around us: How to use our surroundings for more meaningful language acquisition?

The aim of this seminar activity is to acknowledge, how every educator could take advantage of the surroundings for better and more meaningful language acquisition.

For example, taking the learners ourtside to town, to class trips, museums etc. could be turned into a useful language learning experience by preparing certain tasks for it, e.g. a booklet with a variety of tasks, questions, which would draw learners’ attention to the language that appears on their way (street names, information boards etc.).

One sample booklet is added, and it could be used for discussion with learners:

- Why are there different kinds of tasks?

- Why is it in form of discovery learning (learner knows the task, but chooses when to solve which one or when this information appears)?

- What is the main aim – the accuracy of the language or widening the repertoire?

- Which modifications could be done with such task? Please, give reasons.

Immigrant students in Nordic educational policy documents

Chapter in a book: Hanna Ragnarsdóttir; Lars Anders Kulbrandstad (2019).Learning spaces for inclusion and social justice : success stories from four Nordic countries. Newcastle-upon-Tyne : Cambridge Scholars Publishing

Research in political sciences asserts that the enactment of laws and regulations is but one element in the chain of forming and implementing educational policy. Nonetheless, the study of such steering documents can shed light on what the authorities consider as central values and goals to be promoted through education, what they see as new challenges in society and how theses should be met in the educational system. The chapter offers a comparative analysis of the treatment of children and students with an immigrant background in such documents from preschool to upper secondary school in all five Nordic countries.