Northern Ireland: A Precarious Peace?

On 21st September 2024, first and second-year Skytte students Institute were invited to Northern Ireland by Queen’s University Belfast to attend a week-long programme on The Troubles, an ethno-nationalist conflict between the predominantly Catholic nationalist community and the predominantly Protestant unionist community. This was in fulfilment of our ‘Practical Field Research in Conflict Areas’ programme and which provided us all with a unique perspective on the conflict. In total, twelve students and two faculty members, Dr Eiki Berg and Dr Stefano Braghiroli took part in the trip.

Before arriving in Belfast, we spent several in-class sessions going through the background of the conflict. This gave us a foundational level of knowledge that we could then later build upon during our trip. For many in the class this was likely the first time they had studied the conflict in any meaningful depth. Yet it was, at its height, the most serious internal security crisis a Western European state faced since the Second World War. Between 1968 and 1998 the conflict claimed the lives of close to 4,000 people and injured almost 50,000 others.

Landing in the Republic of Ireland, we hopped onto a coach and drove up into Northern Ireland. Admiring the beauty of the Northern Irish landscape, we caught glimpses of the political divide that we would soon familiarise ourselves with. Along the route were Irish flags and British flags. Though in a few places there were other flags which had British symbols but were not quite the same as the standard Union or Ulster flag. They were, as we later found out, flags of paramilitaries.

A troubled history

What is now known as the Troubles was a continuation of nine centuries of conflict between the islands of Ireland and Britain. From the 12th century Anglo-Norman invasions of Ireland, the 16th-17th century colonisation efforts by Scottish and English Protestants in the north and the subsequent repression of the indigenous Irish Catholics, to the Catholic civil rights movement of the mid-20th century, these all helped shape the sectarian divide of modern Northern Irish society.

Image: Murals from the Belfast’s Protestant neighbourhood – Sandy Row (Source: Eiki Berg)

Following centuries of unsuccessful rebellions against British rule Ireland won its independence in 1921, though it did so on the condition of partition. The predominantly Protestant six counties of the northern Ulster province remained part of United Kingdom whilst the remaining twenty-six counties formed what is now the Republic of Ireland. The Catholics in the north soon found themselves as a minority and were subjected to religious discrimination. Catholic opposition to the mistreatment culminated in the creation of various civil rights organisations, and by the late 1960s it was a major political movement. The movement’s civil disobedience was, however, quickly met with heavy-handed police actions.

In response, the nationalist Irish Republican Army (IRA) which had never accepted the partition of Ireland restarted their armed campaign against the Northern Irish authorities. Feeling under threat, Protestant communities formed their own paramilitaries. Violence between the two communities escalated, and by 1969 the British Army had been deployed. What first began as a fight for Catholic civil rights quickly spiralled into an ethno-nationalist conflict in which the predominantly Catholic nationalists sought a unified Ireland and the predominantly Protestant unionists fought to remain part of the United Kingdom.

By the 1990s there was a growing acceptance that political violence was ineffective, and both republican and loyalist paramilitaries began exploring a peaceful resolution to the conflict. In 1998, the British & Irish governments with republican & loyalist paramilitary groups, under the mediation of the United States and the European Union, signed a peace agreement now known as the Good Friday Agreement. Despite being one of history’s most celebrated peace agreements which, among other things, enshrined state power-sharing for unionists and nationalists, ‘peace’ in Northern Ireland has often been precarious. Neither side has ever conceded defeat, Brexit has opened old wounds vis-à-vis British and Irish identity, and dissident paramilitary groups who reject the peace process continue to be pervasive in certain areas.

Streetwalking in divided Belfast

Dr Dominic Bryan, an anthropologist at Queen’s took us to two contrasting areas: the Falls Road and Shankill Road. Dominic’s tour highlighted the contemporary segregated nature of Northern Irish society; over a busy bridge in the centre of Belfast we were shown where Protestant neighbourhoods ended, and Catholic neighbourhoods began. As we walked further, we came across the Cupar “peace line”, a literal wall that separates the two communities. It was shocking to discover that almost 25 years after the Good Friday Agreement, many people from these communities maintained their self-imposed segregation. Our presence in these areas was noticed; drivers honked their car horns at us and people walking by gave curious glances. No offence was meant by it, though as Dominic spoke to us a small group of teenagers attempted to pelt us with bottles.

Image: Section of the Cupar Peace Line (Source: Lewis Barclay)

Falls Road was noteworthy not only for its murals and memorials dedicated to the republican cause, but also for the imposing Divis flats that towered over the area. Perhaps most impressive was the Garden of Remembrance – a large memorial dedicated to the Provisional IRA Belfast Brigade. Yet, what I found surprising was the support for foreign nationalist movements. In the Garden of Remembrance, a Palestinian flag flew alongside an Irish flag, and nearby we saw murals in support of Palestinian nationalism. It was fascinating to see how Irish republicans framed their armed campaign alongside other nationalist conflicts.

Image: The Garden of Remembrance (Source: Lewis Barclay)

Shankill Road on the other hand was noticeably far more unionist, which like Falls Road expressed its allegiance through flags and murals. In contrast to the tranquil Garden of Remembrance, we were confronted with the Bayardo Bar memorial. The memorial was situated on the former grounds of a bar which was subjected to a particularly brutal attack by the Provisional IRA Belfast Brigade – the same Brigade commemorated in the Garden of Remembrance – in which five people were killed and over 50 others injured. In contrast to the Garden of Remembrance, this memorial included photos of the victims as well as graphic photos of other republican paramilitary atrocities. Both memorials elucidated the competing narratives of the conflict; one side portraying their cause as a legitimate military struggle and the other viewing it as indiscriminate murder.

Image: The Bayardo Memorial (Source: Lewis Barclay)

After leaving Shankill we went to Sunflower pub, one of the coolest in Belfast. Pub culture is huge in the city, and the pubs that we frequented were often ram-packed even on weekdays. Having spent all my life in Scotland, I could gauge the cultural similarities between where I had come from and what I saw in Belfast. In a way I felt very much at home. Likewise, throughout our stay the class eagerly indulged in all what the pubs had to offer, from draught pints of Guinness to Irish cider – though I personally preferred Beamish.

Image: Sunflower pub welcoming all sort of crowd (Source: Eiki Berg)

The classroom

The classes were considerably varied and covered the many different facets of the conflict. They ranged from exploring the historical context of the conflict, the peace process, the post-conflict political framework of Northern Ireland, and Northern Ireland’s post-Brexit relationship with the EU. One phenomenon that was raised in several of the classes was the increasingly popular demographic of ‘other’ – individuals who were neither strongly unionist nor strongly nationalist – and how this was reflected in the political makeup of Northern Ireland. This included people who had immigrated from elsewhere, but also a surprisingly large number of Northern Irish people themselves. Could this be a sign of Northern Ireland embracing a post-unionist/nationalist society? It is too soon to tell.

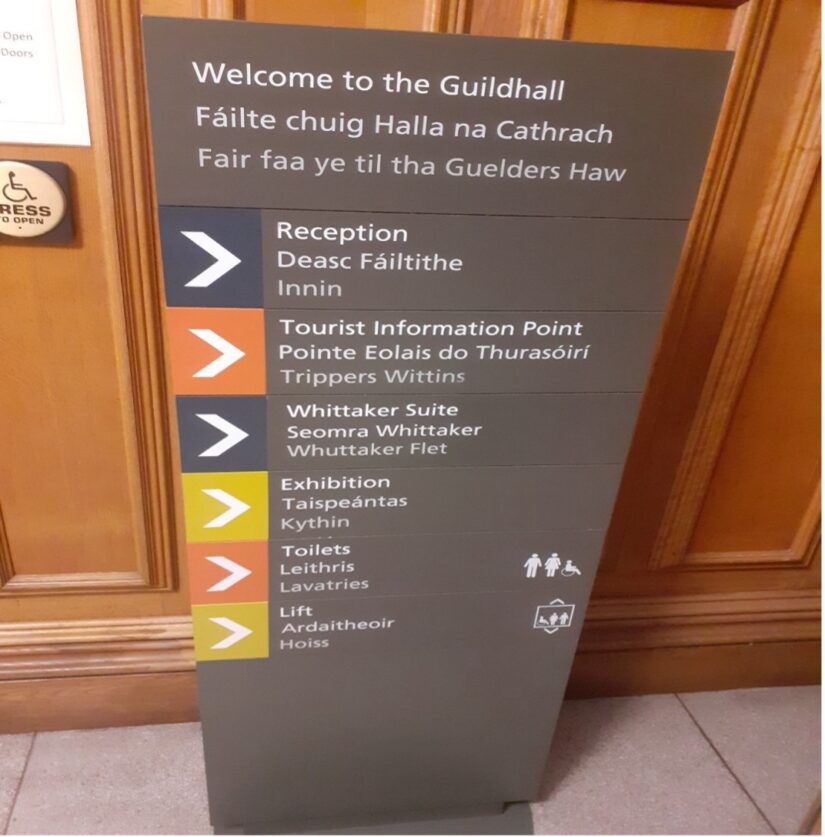

What I particularly enjoyed was the class on the Irish language. Delivered by PhD student Constantin Torve, he took us through the history of the language, its rapid decline during the colonisation period and its subsequent revival. Constantin even taught us a little Irish and introduced us to the Irish hip-hop trio Kneecap. In contrast to the Anglic languages spoken on the island (namely, English and Ulster-Scots, a dialect of the Scots language that had been brought over by Scottish settlers), Irish is the island’s indigenous Goidelic language and a close relative to Scottish Gaelic. During the Troubles the promotion of the language was widely perceived by unionist to be a nationalist ruse for unification. In recent years, however, the state – and many unionists – have championed its use, and it is now considered an official language of Northern Ireland.

Image: The languages of Northern Ireland: English, Irish and Ulster-Scots (Source: Lewis Barclay)

Derry

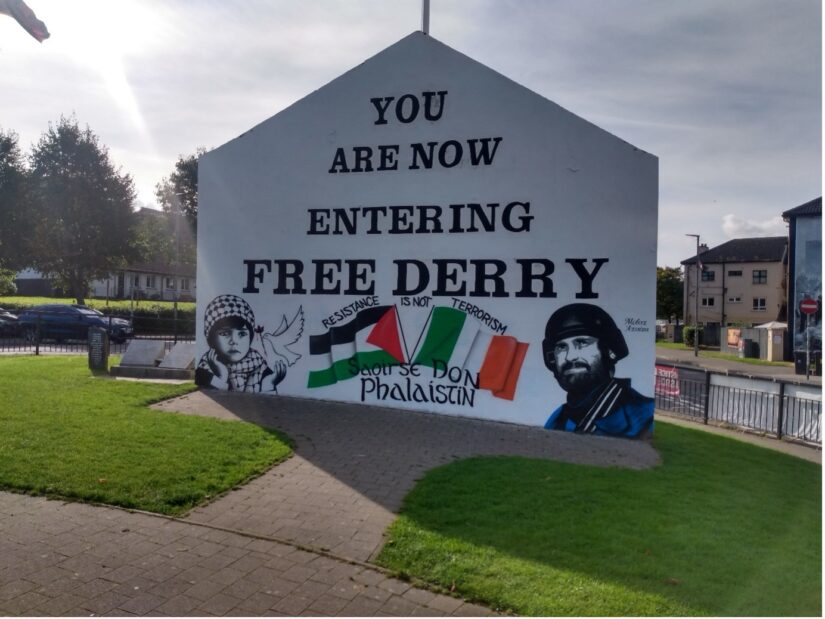

Derry was the epicentre of many watershed moments of the conflict; it is the Derry riots of 1969 between the Catholic population and the police which lead to the creation of the nationalist autonomous area ‘Free Derry’, and which ultimately resulted in the deployment of British troops. It was also the site of a notorious massacre when in 1972 fourteen unarmed civil rights campaigners were shot dead by members of the army’s elite Parachute Regiment. The polarisation of the conflict is even reflected in the dispute over the city’s name; unionists commonly call the city by its official name ‘Londonderry’ whilst nationalists refer to it by ‘Derry’. For the sake of brevity, I will call it Derry.

Image: Derry’s Bogside/Free Derry (Source: Eiki Berg)

Upon entering Derry, we went into the city’s 19th century Guildhall. Following this, we walked along the Derry city walls. These were remarkably well-preserved fortifications that protected the city during the 17th century Jacobite siege. As we approached the end of the wall a group of children from an Irish language school walked by. Many of the Estonians were fascinated as this was likely the first time they had heard the Irish language spoken.

Exploring the city further, we came across an explicitly pro-republican museum. It piqued our interest, and we decided to go inside. The museum was quite surreal. As we entered, we were met with a life-sized mannequin donning a camouflaged smock and balaclava. Surrounding the mannequin were sentimental photographs of paramilitary men, artworks, replica or deactivated firearms, Celtic and Catholic symbols, and a terrain model of a real-life republican assassination operation. After all the horrors I had learned on the trip – including from my own family that had experienced the violence – it felt somewhat disturbing, as though the museum glorified paramilitarism.

Nearby was another museum that primarily focussed on the 17th century siege of Derry. It praised the Protestant Williamites’ fight against the Catholic Jacobites and positively portrayed the marching bands of Protestant fraternities as an intrinsic part of Derry Protestant culture. I was surprised to see this as in the area of Glasgow where I had lived, the similar Orange Order marches were commonly associated with sectarian bigotry. Curiously, there were a few artifacts from the First World War too. Whilst on the surface it appeared odd that these were included in a museum dedicated to a siege that occurred two and a half centuries before it, it fit into the respective ‘blood sacrifice’ myths that both unionists and nationalists cultivated to legitimise their causes. For the unionists, it was the 1916 Battle of the Somme. Likewise, for the nationalists it was the 1916 Easter Rising which precipitated the war of independence.

Stormont

Our last day in Belfast was spent visiting the Parliament Buildings, Northern Ireland’s legislature. The name was a bit of a misnomer as there was only one building. According to our guide, the architect had envisioned several more administrative buildings as well as a dome that was to be placed on the main building. The British government at the time, which was funding the construction, decided one building was enough.

Originally built in 1932, the considerably large Parliament Buildings is positioned atop a hill in the centre of the lush green Stormont estate. Ascending the hill was a bit of a struggle, though the view it gave us of Belfast made the walk quite worth it. The building itself was heavily influenced by Greek architecture, and, as we were told, had perfect symmetry. For a region which at the time had less than one and a half million people, such a building seemed almost disproportionate in its grandeur. Upon passing through the reception, guests come into the Great Hall which completely consists of marble. On either side of the hall there are painted portraits of Northern Irish politicians, including that of firebrand Presbyterian minister Sir Ian Paisley who would become First Minister of Northern Ireland alongside former IRA leader Martin McGuinness who would become his Deputy and close friend.

Image: Stormont – Northern Ireland’s legislature (Source: Carlos Kleimann)

We explored the senate and the assembly chamber, the latter being where the elected representatives met. Unlike the adversarial British House of Commons where members of the government and opposition sit across from one another, separated by a table at two swords’ length, the seating layout in the Assembly resembles something of a u-shape; parties sit alongside each other which reflects the power-sharing dynamic in Northern Ireland. There was I think something very powerful and symbolic with this being the last location on our itinerary. Almost everything else we had seen pointed to the continued divisions within Northern Irish society, and yet here was the room where both unionist and nationalist politicians could sit, discuss, debate, and govern the country together. Such a thing would have been unthinkable in the not-too-distant past, but it nonetheless ended the trip on quite a hopeful note.

A farewell to Belfast

My initial image of Northern Ireland had been admittedly skewed. My mother, a schoolgirl in Derry, would sometimes speak of the normalcy of soldiers using mirrors to check underneath her school bus for bombs. My late grandfather on rare occasions would speak of seeing friends killed and who, just before passing, alluded to still having nightmares from the conflict some forty years later. I knew the violence had largely subsided, but beyond that I did not know what to expect. I instead came across a society significantly different from what my family experienced. Aside from the bottle-throwing incident, at no point during the trip did we feel unsafe or unwelcome. Likewise, whilst there were still social divisions, it became apparent that they had somewhat softened over time. This was illustrated most clearly by the faculty and student body of Queen’s who as we found out came from all walks of Northern Irish society. On the political front, the emergence and relative success of ‘other’ parties, such as the liberal Alliance Party, points to a growing trend of people rejecting a unionism or nationalism at-all-costs mindset. Whether the trend persists remains to be seen.

That being said, the conflict has left an indelible legacy on the society. As we saw first-hand, despite much progress many communities remain in the segregated neighbourhoods to which they fled during the Troubles. Some of these neighbourhoods continue to be plagued by dissident paramilitaries who engage in drug dealing and other antisocial behaviour. Brexit has exacerbated existing divisions and led to some of the worst public disorder Northern Ireland has seen in years. Whilst it is very unlikely Northern Ireland will see a return to the sectarian violence of the Troubles, a degree of uncertainty looms over the country. With a nationalist First Minister for the first time in its history, there is even uncertainty of Northern Ireland’s place in the Union.

Overall, I found the trip to be extremely informative. I was especially impressed by the impartial manner with which our lecturers portrayed a conflict which in some ways has never really ended. Furthermore, it provided us with on-the-ground experience that we otherwise would not have had. From a personal perspective, I was especially grateful that I was given the opportunity to visit the city where members of my family had once lived; it added a new dimension to the stories of the conflict they had told me and at the same time showed how far Northern Irish society has come.

I would like to thank Eiki and Stefano for organising this trip with Queen’s University and express gratitude to the faculty members who took time out of their day to come speak with us. Special thanks must be given to Timofey and Lee who were with us at almost every moment of the trip and who ensured that we were kept safe, informed and entertained.

Author: Lewis Barclay