Research Data Management and Publishing

Documentation of Data and Metadata

Documentation

Working with data should be documented at every stage starting from its collection up to the depositing of data for long-time storage. First, you need to decide, what will be documented in which format and who will be responsible for the process.

As the DMP is an official document, it is not necessary to repeat in detail the issues that will in any case be described in the DMP.

Documentation is important when new researchers and doctoral students join the group. Precise documentation of the data helps to prevent its incorrect use and misunderstanding in the future, which is one of the researchers’ greatest fear.

For example, metadata are added to your data in the course of work, but which standard to use and which fields on the standard to fill in has to be decided earlier and then followed throughout the course of the work. Similarly, the repository where to store the data after the end of the project should also be chosen at the start of the work, because not all repositories support all metadata standards. Subject repositories are able to support rarer subject-related standards.

Documentation and adding of metadata is a process continuing all through the data cycle.

Metadata

Metadata are the data about data. Metadata set research data into context and enable to identify its origin.

The aim of metadata is to make the data searchable, understandable and usable also in the future without requiring additional explanations about the dataset. Metadata describe the research data and enable making searches. You need to determine how to get the metadata (create it yourself, have it created automatically), where to store it and how to link it with your data.

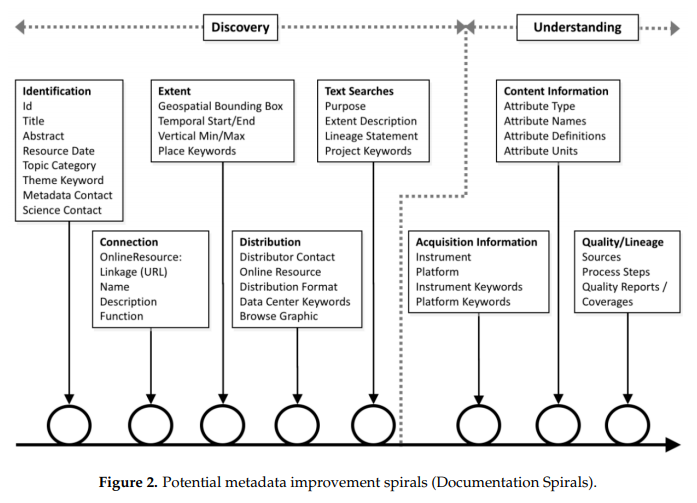

The life cycle of metadata is part of the research data life cycle; it is not sufficient to create it once during the cycle, but it has to be done continuously, by systematically returning to the previous stages.

This process is characterised by the metadata spiral, which also differentiates between the metadata necessary for searching and finding data, and that necessary for understanding and reusing data.

Habermann, T. (2018). Metadata Life Cycles, Use Cases and Hierarchies. Geosciences, 8(5), 179. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences8050179

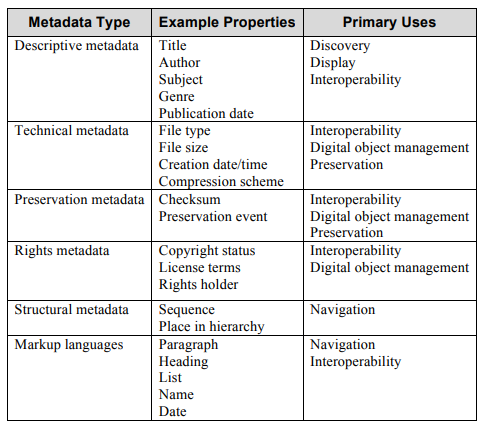

There are three different types of metadata:

- Administrative metadata (about the project and responsibilities, management of access rights, licences, periods of embargo), with the objective of ensuring accessibility of the data.

- Technical and structural metadata (about hard- and software, authentication, encryption, data about the digitisation of its sources, structure of digital objects and the data set, codes, variables, etc.), with the objective of ensuring the interoperability of systems and reuse of the data.

- Descriptive metadata, with the objective of ensuring the findability and understandability of the data (DOI, bibliographic metadata).

The above chart illustrates the importance of the metadata of a data set with respect to the FAIR data. The task of the creator of a data set is to provide it with the metadata which would describe it and specify the related rights. Repositories have to ensure the interoperability of the data, deposited for a long-time storage, with other information systems.

There are numerous more general and also more subject-specific standards and frameworks of metadata, which prescribe the structure and data elements of metadata, taking into account the characteristics of the data collected on some specific subject.

Metadata frameworks and standards use verified ontologies and taxonomies. This means that it is not possible to enter whatever you want on many of the metadata fields which describe data elements, but you have to select the values among the predefined options in a verified ontology. Thus you can ensure the data exchange and interoperability.

In Estonia, The Estonian Subject Thesaurus as a universal controlled vocabulary for indexing and searching is considered as a standard.

Another good example coud be ELSST – European Language Social Science Thesaurus.

Internet search can give you lists of subject-based standards.

DataCite

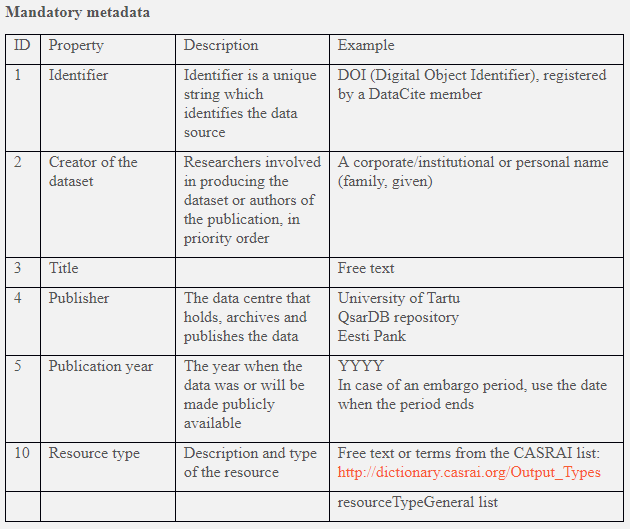

Let us have a closer look at one certain metadata framework.

University of Tartu has joined the non-profit organisation DataCite and the UT Library offers services and allocation, being one of the founding members of the consortium DataCite Estonia. DataCite assigns the persistent identifier DOI to data sets and registers metadata. The UT Tartu data repository DataDOI is recognised by DataCite; all data sets uploaded to this repository are assigned DOIs and they are findable with DataCite search just due to the metadata.

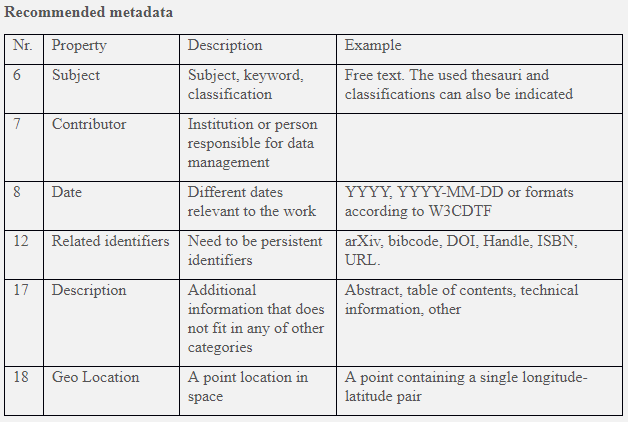

The DataCite metadata framework divides metadata into three groups: obligatory, recommended and optional metadata.

Description of obligatory and recommended metadata:

Metadata are open for public even if the data set itself is, for some reason, not accessible for all. Metadata are persistent and their life cycle is longer than that of the data, which are described by this metadata.

The larger the amount of metadata, the easier it is to find and interpret a dataset!