The Fallen Dove of Peace

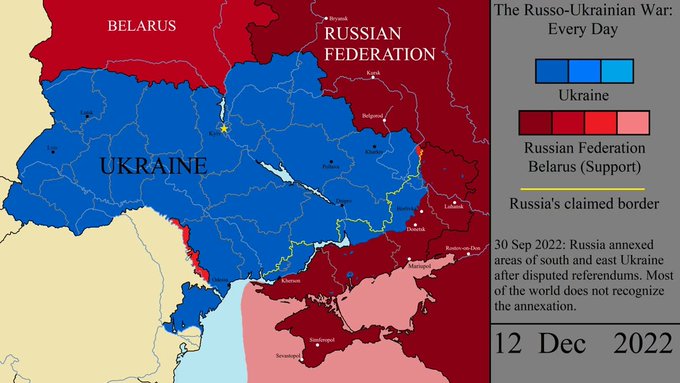

On December 12, 2022, a group of Azerbaijani protesters blocked the Lachin corridor cutting off 120.000 ethnic Armenians of Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh) from the outside world. The road is under the control of the Russian Peacekeeping forces and is only used for passage of people and goods intended for the civilian population of Artsakh. When a group of Azerbaijanis in civilian clothes, posing as alleged environmental activists blocked the road, it resulted in a complete blockade that stopped the movement of people as well as import of food, medical supplies, and other basic necessities.

In a video that went viral in social media, one of the ‘eco-activists’ wearing a fur coat is holding a breathless dove in her hand while chanting peace in the planned campaign to release 44 doves (the number of days that the 2020 war launched by Azerbaijan lasted) as a symbol of peace. As she released the dove, it fell dead under the feet of the protestors becoming an unfortunate symbol of the prospects of peace in the context of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. While after the 2020 war the Armenian government started to promote the peace agenda, and even ran a winning electoral campaign on it, the Armenian public never saw it as a feasible option with the growing anxiety over security of not only Karabakh-Armenians but also Armenia’s sovereign territory. These fears have been growing daily with Azerbaijan’s aggressive policies towards Armenians and with the September 2022 military aggression, where it occupied territories from Armenia proper. The blockade of the Lachin corridor became the last drop proving the impossibility of enduring peace in the region in the coming future.

The humanitarian situation

“There is no food, there is no cash, there are long lines in front of the banks, there are long lines at stores, hoping they can get whatever’s available, there are medical patients in severe condition, there are separated families, there is no infant food, and many more such problems.” – says a young resident of Artsakh.

Image: Empty shelves of the grocery stores in Artsakh (Source: Anush Sharhamanyan’s FB page)

Recent reports from various international organizations such as UNICEF and Human Rights Watch, as well as the Human Rights Defender of Armenia highlight that there is urgent action needed, since the risk of a famine in Artsakh is getting higher daily. Below are the latest figures:

- 120.000 people under complete blockade including 30.000 children.

- 1100 locked out of Artsakh.

- Several villages in Shushi region completely cut both from Armenia and from Artsakh.

- Severe shortage of food, medical and energy supplies (previously around 400 tons of essential goods, including grain, flour, vegetables, fruits, economic goods, etc., were imported to Artsakh from Armenia daily). Only once on December 25, 2022, 10 tons of humanitarian aid was transferred to Artsakh through ICRC.

- 350 patients that need medical treatment or are in critical condition cannot transfer to medical centers in Armenia. There have been only 2 cases when with the support of the ICRC patients were transferred to Armenia including a 4year-old in a critical condition.

As an addition, Azerbaijan occasionally cuts gas and electricity supplies under the guise of repair works – a practice it adopted since the 2020 war. “For the past two years, we’ve had constant problems with electricity, water and gas. When we have water, there is no gas, something is always missing. But it is secondary to the difficulties we have now with shortages of food and medicine.” Marut Vanyan, a journalist, tells the BBC.

Azerbaijan’s window of opportunity

The declared reason of the Azerbaijani eco-activists for blocking the road and setting up tents has been the demand to access mining sites inside Karabakh and that the Azerbaijani government be allowed to inspect those. It did not take long for investigative journalists to fact check and reveal that the self-proclaimed eco-activists that have blocked the Lachin corridor are in fact representatives of different organizations funded by the Azerbaijani government that have nothing to do with environmental activism. As an addition, Azerbaijan, known for its quick reaction in suppressing any grassroot demonstrations and even daily activities of civil society, is quite enthusiastically supporting the demonstrators, and airing the protests live on TV channels.

Image: Azerbaijani protestors and Russian Peacekeepers (Source: MENAFN.COM)

What is then the reason to block the corridor? First, in its attempts to ‘solve the Karabakh problem’ Azerbaijan is trying to penetrate and ensure presence inside of Artsakh and establish total control over it. The presence of this mining inspection body would open room for demanding other types of control and oversight, slowly gaining full control over the territories. The second reason, that explains Baku’s motivation, is Azerbaijan’s discontent with the presence of Russian peacekeepers in the region. The state-controlled media have been promoting the narrative that the peacekeepers are failing to prevent illegal mining and the entrance of military equipment into Karabakh. As the power balance is quickly altering because of Russia’s war in Ukraine, Azerbaijan is trying to take advantage of weakened Russia and use all chances to remove the peacekeepers from the region. This also explains Western tacit approval or at least lack of action against Azerbaijan’s blockade of Karabakh. What’s even more, even the blockade is framed by Ilham Aliyev state propagandists as if the protestors have not blocked the road, but it is the Russian peacekeepers who are not allowing free movement. Finally, the blockade is a leverage to be used while negotiating with Armenia. Experts consider that the blockade could also be a response to Armenia’s resistance to provide an extraterritorial corridor (which would cut Armenia in half and from the border with Iran, which – along with Georgia – is the only open borders for Armenia) to connect Azerbaijan with its exclave Nakhijevan and Turkey. However, the 2020 November 9 trilateral ceasefire agreement has no mention of an extraterritorial corridor, but simply mentions the unblocking of regional communication, which Armenia has on multiple occasions expressed willingness to conduct.

Russia’s weakening influence in the South Caucasus

Russia is trying to actively create an impression that the situation is under control. While some experts consider that Russia does not have enough leverage to enforce opening of the road, others claim that Russia is in fact cautiously interested in pressuring Armenia into opening the road connecting Azerbaijan with Nakhijevan. Russia aims to have its FSB forces overseeing the security of the road (as signed by the leaders of the state according to the trilateral ceasefire announcement) and give it more leverage over the sides. On the one hand, Russia’s response has been quite limited even in situations where its position in the region was openly challenged. For instance, Russia’s representative told at the UN Security Council Session that the traffic in the Lachin Corridor has been partially restored, while Azerbaijanis did not even allow the peacekeepers to pass through the corridor on December 21, 2022. Russia is quite cautious in its actions in Artsakh, since it understands that the presence of peacekeepers is not welcomed by Azerbaijan and in case of any acts of violence against the protestors, Azerbaijan will even further try to challenge Russia’s role in the region.

On the other hand, sanctioned by the West and dealing with economic and strategic hardships, Moscow is more closely allying with Turkey and Azerbaijan as alternative routes to international markets. Turkey has become a key ally in trade and sanction evasion especially for the export of Russian oil and gas and import of technologies. At the same time, it has increased its economic ties with Azerbaijan exporting gas there, which in turn sells it to Europe. Moreover, 5 days into the blockade of the Lachin corridor, the leaders of Azerbaijan, Georgia, Romania and Hungary signed an agreement in Bucharest to bring Azeri energy to Europe. Von der Leyen even mentioned that the EU’s strategy to decrease the use of Russian fossil fuels and turn towards ‘reliable energy partners’ was working. This has caused outrage among Armenians who find it unacceptable that the EU is ready to ‘swap one dictator for another for economic interest’ while choosing to not show the same level of moral integrity in responding to Azerbaijan’s invasion of Armenia, like it does in case of Russian invasion of Ukraine.

While in this conjuncture everything seems to work economically, Russia has been more disinclined in imposing its position on Azerbaijan and applying pressure against the Azerbaijani-Turkish alliance. In fact, being able to pressure Armenia into providing a corridor would be beneficial for Russia since it hopes for controlling the corridor and decreasing its economic costs of ground trade and transportation with Turkey bypassing Georgia.

Karabakh Armenians demanding security

On December 25, 2022, around 70.000 Armenians of Artsakh (over half of the population) gathered in Stepanakert to express their demand for ending the blockade. This was the biggest protest even compared to the one that took place on October 31, 2022. There were, however, some notable differences. This time there were no Russian flags or other symbols present at the protest, which is a serious sign that there are significant changes of sentiments towards Russia not only among the public but also among the ruling elite of Artsakh. If before the elites were hoping to gain security dividends by maintaining positive relations with Russia, they are now more hesitant and skeptical despite the reassurance of the newly appointed State Minister Ruben Vardanyan that peacekeepers are doing what they can. Moreover, he said that criticizing the peacekeepers is essentially the same as helping Azerbaijan, because now they are the only guarantee of safety of Artsakh Armenians. The official Azerbaijan, in its turn has been constantly demanding that the Russian-Armenian businessman, who just recently gave up his Russian citizenship moving to Artsakh should be removed from his spot, raising the issue even in Moscow.

Image: December 25, 2022, protest in Stepanakert, capital of Artsakh (Source: IG page @dinjkac)

With Russia’s inability or unwillingness to end the blockade and ensure the security of Artsakh Armenians, the public is increasingly critical of not only Moscow’s policies but also leaders of the local peacekeeping units. Although clear that the rallies would not end the blockade, this was an important step for Artsakh Armenians in showing their position (that being – Artsakh Armenians cannot live safely under Azerbaijani control). The safety concerns of Armenians have been dismissed by Azerbaijan, which claims that Armenians will have all the rights that Azerbaijanis have, meaning there will be neither security guarantees nor any special status. Having seen how all territories that appear under Azerbaijani control are systematically ethnically cleansed, accepting the sovereignty of Azerbaijan over Artsakh is not even a matter of consideration for Artsakh Armenians. They are sure that the blockade is also a way to put psychological pressure, showing them the perils of remaining in Artsakh and eventually squeezing them out. These pressures become evident while the ‘eco-activists’ often play the Azerbaijan anthem, use gray wolves symbols (which is a Turkish nationalistic organization considered a terrorist organization in the EU) and employ other nationalistic symbols that cause immense distress for the Armenians blocked in Karabakh.

Nevertheless, understanding the crucial situation with a humanitarian catastrophe at the door Artsakh authorities have been trying to advance two alternatives:

- While rejecting the demands of a solely Azerbaijani state inspection, Karabakh’s leadership suspended the production operations at the copper and molybdenum mine, expressing willingness to welcome an international ecological examination. Baku has not responded to this. In short, Karabakh is doing everything to prevent Baku from entering Karabakh.

- Trying to use all its diplomatic resources along with Armenia to achieve a so-called air bridge for delivering essential food and medicine to the civilian population. This as well, has been ignored by Baku, which has long threatened to shoot down anything that flies to or from Stepanakert.

Armenia caught between the bad and the worse

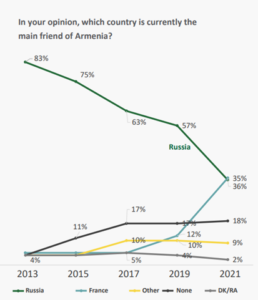

In this whole situation, what remains unclear is what are the red lines for Armenia. It has no allies (if there ever can be any in the absence of Western interests) that are practically able to provide security guarantees against aggression of the Azerbaijani-Turkish alliance, neither to Artsakh Armenians, nor to the Republic of Armenia. After the 2020 war and all escalations thereon, in an attempt to balance its position between Yerevan and Baku Moscow’s reluctance to respond to its ally’s security challenges and official requests, has affected the public opinion in Armenia, where now only 35% consider it Armenia’s ally.

Image: Caucasus Barometer Report 2021-2022, Russia’s declining reputation in Armenia (Source: Caucasus Barometer)

These sentiments started to reflect also in terms of official discourse especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Further the September invasion of Armenia by Azerbaijan and the increased Western attention – but lack of action – in the conflict seem to have changed the Pashinyan government’s relations with Russia.

So far Armenia’s response to the blockade has been the use of diplomatic measures and constant ‘unpleasant reminders’ to Russia that it has lost the influence over deterring Azerbaijan. Pashinyan says Azerbaijan is preparing a genocide in Nagorno-Karabakh and Yerevan “expects more practical steps from the international community… [and] Russia.” The US, the EU, the UN Secretary-General along with more than a dozen countries have called for Azerbaijan to unblock the Lachin road. No response from Baku, and yet no more pressuring follow-up statements or actions from international capitals. On the other hand, Moscow has expressed concerns saying that it has been ‘negotiating with the sides’. During the past weeks Armenian officials have made a few statements that experts think might have high costs for Yerevan. For instance, during the meeting of the Commonwealth of Independent States in St. Petersburg on December 26, attended both by Aliyev and Pashinyan, the latter told Putin “it turns out the Lachin corridor is not under the control of the Russian peacekeepers.” Later Pashinyan also called on Moscow to seek a UN mandate for its peacekeeping mission in Karabakh or open the door for a multinational peacekeeping contingent. Yet another discontent with Moscow was expressed by Armen Grigoryan, the Secretary of the Security Council of Armenia, who claimed during his interview on Public TV that Russia and Belarus are pressuring Armenia to join the Union State, later denied by Moscow.

With the available information it is questionable that Russia would have any benefit of making Armenia a part of the Union State. But even if so, this harsh rhetoric might end up being fatal for the future of Armenians, since, as mentioned on multiple occasions, Armenia has no capacity to secure itself and the Karabakh Armenians. Even if Russia’s presence in the region is a matter of political calculation, they still are practically the only factor that prevents the bloodshed in the region. While Armenia is counting that the West will start to pay more practical attention to the region, it might be carelessly deteriorating the only security guarantee it has and in this given conditions it is unclear what the Armenian government’s endgame is. So far, it seems extending time has been the only strategy.

Fragile negotiations

There are two drafts of a peace deal between Yerevan and Baku that have been circulating at the negotiation tables: one by Russia, one by Armenia and Azerbaijan with Western mediation. While the document proposed by Moscow postpones the status question of Karabakh, the Western-mediated one largely suggests giving up on Karabakh hoping that Azerbaijan will ensure the civil rights of Karabakh Armenians. Armenia is caught up in a situation, where it has to choose between the sovereignty of Armenia and the safety of Karabakh Armenians (with no guarantees of any), as an addition to Azerbaijan’s maximalist demands. In the given conditions negotiations are heading on to a dead end where Armenia is trying to win time and Azerbaijan is trying to take all the advantages it can from Russia’s weakened position in the region. Then if talks go nowhere, Azerbaijan will take what it can by force as ICG predicts (predicting a possible war in a yeartime), considering that Azerbaijan exceeds Armenia by military power multiple times and has already shown its willingness to solve the conflict on its own terms if no bigger power will stand in the way. It seems the dove of peace is dead with the given (im)balance of power in the region.

Author: Azniv Tadevosyan