The Conflicts in Georgia and Ukraine in Kremlin’s Transcripts

We live at times when the amount of information useful for analysis exceeds our human capacities to analyse it directly. But our technological ingenuity helps us out. There are tools that can automatically collect texts from online sources like web pages and not only save and process them, but also analyse them in substantively meaningful ways. Analytical techniques that were once the purview of qualitative discourse analysis – analysing the chains of relationships between “chunks” of meaning like words – are now to some extent available through quantitative text analysis.

One such tool, an unsupervised machine learning model that mimics the logic of how texts are generated, is called topic modelling. It is a model, which assumes that each text is a mixture of different topics. A topic is a bundle of words that have a high probability of appearing together in the analysed texts and are distinctive for one particular topic. They represent words that have something in common through being used together in some contexts but not in others.

Of course, there are limits to how much “machines” can “learn”. Such a model of text is only able to determine what it thinks such bundles of words are. It is up to the analyst to determine what the meaning that ties them together is. Fortunately for us, these kinds of models work surprisingly well. They are able to detect topics that in most contexts are remarkably intuitive and interpretable for anyone who is familiar with the subject matter. Let’s have a look at one specific example from a set of official transcripts of the Kremlin.

The Kremlin has published a large amount of transcripts that are constantly updated and date back to the start of the Putin presidency. Speeches, statements and comments by the president are both in Russian and English. One could read and analyse them qualitatively, but this is a gargantuan task. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if “machines” could help us out? But they can. It is possible to use topic modelling on these texts in order to detect the most prominent themes that appear across the documents. And there are many. A model that was asked to discern 100 topics across the transcripts was able to detect topics form sports to religion to various topics of international affairs.

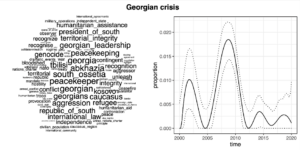

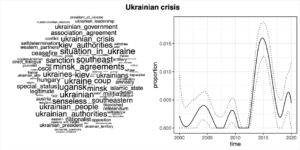

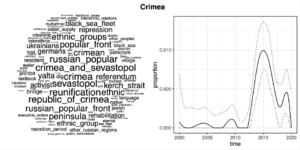

These figures below reveal the most distinctive words for each topic as well as the association with time. The association with time shows the temporal occurrence of the topic in transcripts. The dotted lines indicate the 95% confidence intervals that were estimated from the model. We see three topics – one that refers to the Georgian crisis, one to the Ukrainian crisis and one to Crimea. Let’s look at and think about them in temporal succession. The three topics that are brought out here show how some recent conflicts appeared in the discourse of the Kremlin.

The topic of the Georgian crisis peaked in 2008. The model detected faint echoes of it already before, but after about 2010, this kind of discourse was almost completely off the agenda. Among the words that define the topic, we see references to the regions involved as well as the key terms that Russia used to justify its intervention – “peacekeeping” and “humanitarian assistance” in order to prevent “genocide”. We also see a connection to “Kosovo”, which played a key part in Russia’s strategy of justification – it did in Georgia by and large what it has said that the Western countries did in Kosovo.

The next major crisis involving Russia and countries that are in limbo between the East and the West happened in 2014 with the crisis of power in Kiev, the separation of Crimea from Ukraine and its incorporation into Russia. It is noteworthy that the model detects two separate topics that are related to the 2014 Ukrainian crisis – one that addresses the events in Kiev and in Eastern Ukraine and another that is about Crimea.

The topic about the Ukrainian crisis refers directly to the events in Kiev and frames them in terms familiar from the general Russian discourse on the issue (as a “coup”). We do see some keywords in this topic that refer to international law and international order like “self-determination”, but in comparison to the topic on Georgia, which included many direct references to international order (like “international law”, “united nations charter”, “territorial integrity”), we see that the topic on the Ukrainian crisis is rather distant from this vocabulary. The crisis in Ukraine is presented much less in the framework of international norms and order.

And it is notable that Crimea is a topic that is completely separate and in a different domain. It contains no references to the crisis in Ukraine. Instead, it includes geographic and legal terms (“Republic of Crimea”), references to the local population (“ethnic group”) and processes such as “referendum” and “reunification” with Russia. What happened in Kiev (and in Eastern Ukraine) is carefully separated from the question of Crimea and the latter is from the outset portrayed as an internal Russian matter.

This is but a small piece of what this kind of an analysis can reveal. With no other substantive input than the texts to be analysed and the number of topics to extract, topic modelling is able to detect core themes from among a numerous set of texts as well as determine their association with one another and additional characteristics of the texts like the time of their production. This can serve as an analysis in its own right as well as a first step for further analyses.

Author: Martin Mölder