MOOC: Auditing waste management

2.2. Economics of waste management

Waste is part of the economy – it is a by-product (output) of economic activity by businesses, government and households. Waste also forms input for economic activity, whether through material or energy recovery. The management of this waste has economic implications – for productivity, government expenditure and, of course, the environment. []

Waste-related revenue and expenditure

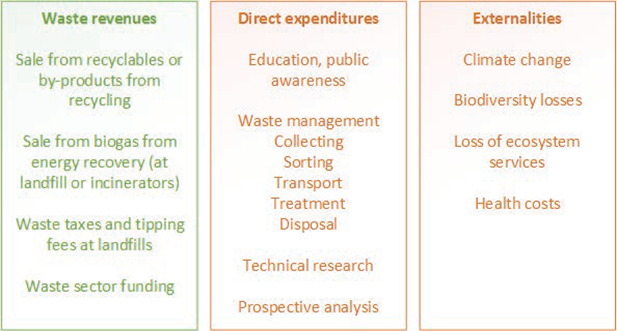

From an economic point of view, the generation of waste creates both expenditure and revenue. While generators of waste often pay for its disposal and treatment, these costs constitute revenue for actors operating within the waste sector.

Figure 12. Waste-related revenue and expenditure []

Private actors operating in the waste sector may generate revenue from the sale of recyclables, the by-products of recyclables, the sale of biogas from energy recovery or waste sector funding. High energy and raw material prices increase demand for these activities.

Costs are mainly related to the direct costs of collecting, sorting, storing, transporting and treating waste. In addition, the cost of raising public awareness on waste issues and research can be included.

Externalities are costs or benefits that are not borne by the waste generator – these are not reflected in the prices charged for the goods and services. Negative externalities occur when neither producer nor consumer covers the costs of negative impact to the society. Therefore, they are cause of market failure.

In the case of waste management, externalities tend to be mainly negative ones. For example, health and environmental impacts may be caused by improper landfilling or incineration – recall Module 1 – which are as a result born by people, businesses and governments. To address negative externalities, the internalization of costs (shifting the cost from external to internal in the budgets of projects or policies) through different pricing tools and subsidies is undertaken. For auditors, it is important to review and understand where the externalities are and if these are approached by policies and tools to get the prices ‘right’. It is also worth bearing in mind upon investigating concrete waste projects or policies that internal costs should not be reduced on the expense of increasing the external ones.

AUDIT CASE: ECONOMIC VIABILITY OF WASTE MANAGEMENT

AUDIT CASE: ECONOMIC VIABILITY OF WASTE MANAGEMENT

| Morocco – Management of the public service for the disposal of solid waste in Casablanca In 2016-2017, SAI Morocco audited the solid waste management service in Casablanca (public waste dump). One of the lines of enquiry in this audit was whether the solid waste management was economically viable. To this end, the financial balance of the delegated management contract for the Casablanca landfill was taken under review by the auditors along with its business plans and financial statements. Additionally, the auditors made a comparative analysis for benchmarking the contract with similar ones in other public landfills. SAI Morocco concluded that the delegated management contract was unbalanced and in favour of the delegate, making the solid waste management system economically unsustainable. Recommendations were made with a view to ensure that the contractual commitments related to investments were respected and that remunerations of the delegate and the household waste collection companies would be calculated on the basis of the quantities actually landfilled. |

Tip for auditors

Tip for auditors

Understanding the economics of waste in your country will help in analysing the causes of problems and in suggesting recommendations to improve the situation.

Economic obstacles to recycling

The waste hierarchy ranks the various waste management options broadly according to their environmental desirability (prevention, reuse and recycling being preferred). However, it does not include economic considerations. If the collection and processing costs of waste are lower than the value of the recycled end-product, recycling makes economic sense. For example, aluminium, steel, paper and plastics (PET and HDPE) can be collected in high volumes, processed at relatively low cost and then brought back to the market for a profit. []

However, there remain several waste streams which are not as economically viable for recycling compared to using virgin raw materials and instead dumping or incinerating them, e.g. certain plastics and mixed material products.

Without government intervention, waste treatment options with better environmental performance may be penalised relative to treatments with poorer performance due to higher costs. For example, incineration may prove economically more profitable compared to recycling and consequently decrease incentives for recycling. Governments could improve recycling infrastructure by making producers responsible for the waste generated and by making disposal less attractive. Accounting for this externality would require the costs of various treatment options and levels of the hierarchy to fully reflect the environmental externality of each option. Additionally, governments could impose regulation to level the playing field and incentivize environmentally friendly options, e.g. banning single-use plastics.

AUDIT CASE: INCLUSION OF COSTS IN PAYMENTS FOR WASTE MANAGEMENT

AUDIT CASE: INCLUSION OF COSTS IN PAYMENTS FOR WASTE MANAGEMENT

| Latvia – Inclusion of costs in payments for waste management In 2015, the State Audit Office of the Republic of Latvia carried out a performance audit on municipal waste management wherein one line of enquiry for the SAI was whether local governments had ensured that only justified expenses were included in waste management payments. Three following criteria were established: waste management enterprises include only economically and technologically reasonable expenses to payments necessary for effective provision of service; waste managers weigh waste either on-spot or the amount of waste is weighed using sound conversion methodology; disposal fees are applied only for the disposed waste excluding sorted and recycled waste. SAI Latvia analysed invoice databases and concluded that a total of 3,6 million EUR had been overpaid within 2,5 years due to incorrect weight-to-volume conversion methodology and excessive natural resource tax levied on waste not actually disposed to landfill sites.

|

Transboundary shipment of waste

Since waste is generated, treated and recycled in different locations, waste is a subject of international trade. For example, most scrap plastic is transported to and treated in Asian countries. Problems arising from waste (as described in Module 1) often do not remain within a country’s borders but are dispersed across countries. Health and environmental problems are therefore exported from one country and imported into another.

Waste crime

The economic incentives for illegal or unsound waste management are large. Illegal waste operators may be paid large sums to dispose of waste in a safe manner, but instead dump the waste. They do this because of the high costs of securing sound management. Dumping may occur at waste disposal sites, on private or public land or at sea.

The mixing of waste streams is frequently revealed by environmental authorities. By mixing hazardous and non-hazardous waste streams, waste handlers avoid sorting and treatment costs.

Large amounts of e-waste are illegally exported to Asia and Africa from other continents, often being erroneously declared as second-hand goods. Waste crime poses a great risk to the environment and to human health, as well as creating opportunities for money laundering and tax fraud. To reduce the probability of waste crime, environmental regulations, monitoring and enforcement systems must be in place.

Below is an example video on how waste-related problems in developing countries can be caused by developed countries due to insufficient controls over waste handling and waste fraud:

Below is an example video on how waste-related problems in developing countries can be caused by developed countries due to insufficient controls over waste handling and waste fraud:

Video. E-waste hell

Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=270&v=dd_ZttK3PuM

AUDIT CASE: ECONOMIC VIABILITY OF WASTE MANAGEMENT

AUDIT CASE: ECONOMIC VIABILITY OF WASTE MANAGEMENT Tip for auditors

Tip for auditors