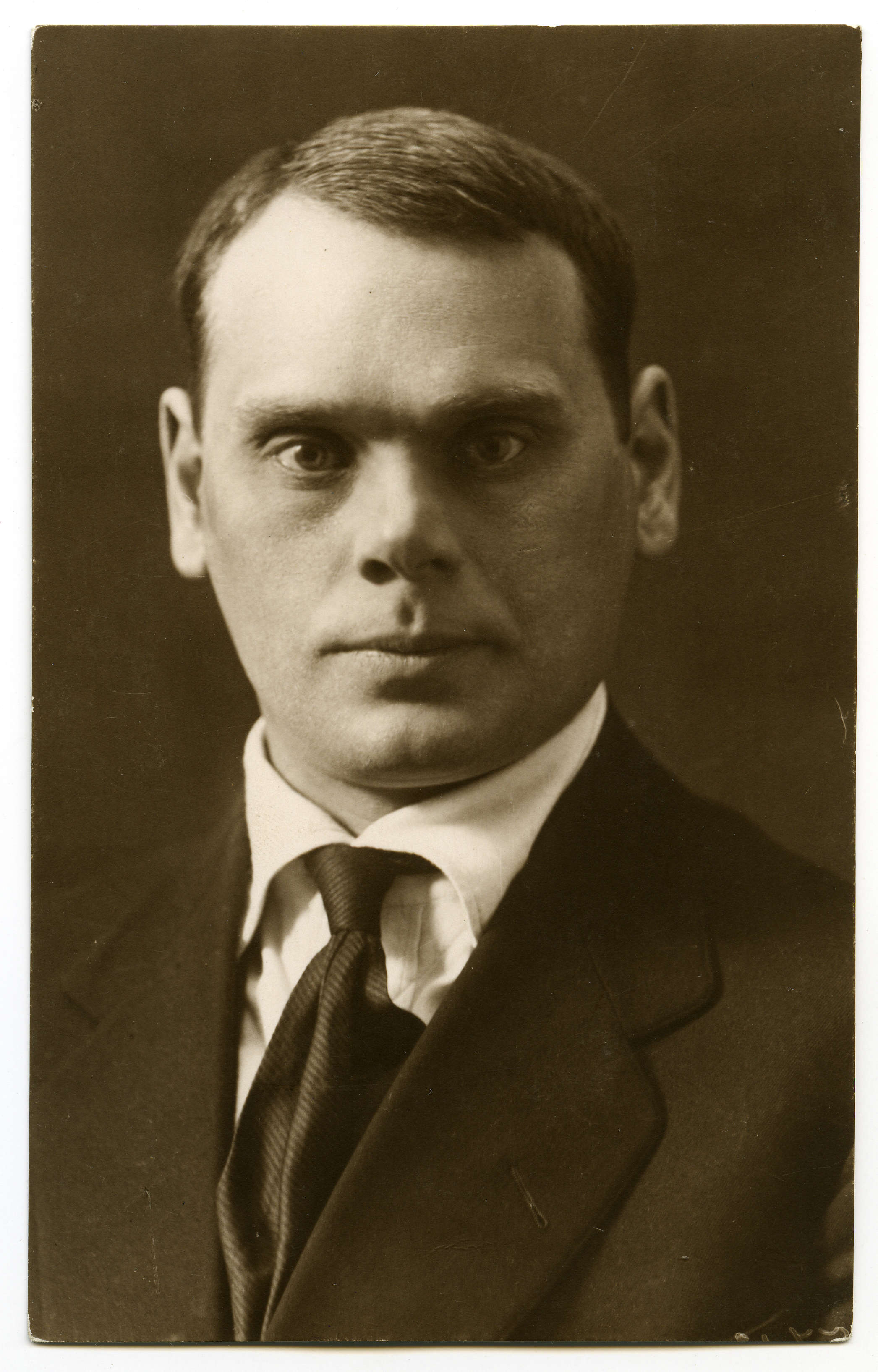

Aleksander Tassa

Aleksander Tassa (7. VII / 25. VI 1882 – 23. III 1955) was a prose writer, playwright, artist and art historian; as a writer, he was mostly known for his neo-romantic, fantastic short prose written in the 1920s.

He was born a son to a school clerk in Tartu. He studied at Tartu county school but did not graduate and at the same time, took drawing courses at the German Artisan Society with the Baltic German artist R. J. von zur Mühlen. From 1900-1903, he worked as an office clerk in Tartu. In 1904, he began attending the Baron Alexander von Stieglitz’s School of Technical Drawing but was expelled the next year due to revolutionary actions. In 1905, he began his studies at the Ants Laikmaa art studio in Tallinn but left in 1906 and briefly studied at J. Goldblatt studio in St Petersburg. From 1906-1913, he travelled Europe, getting acquainted with art and culture and producing visual art himself, mostly while in Paris, but also when staying in the Åland Islands, Helsinki, Norway, Denmark, Germany, Switzerland and Sweden. His travel and creative companions were Konrad Mägi, Jaan Koort, Nikolai Triik, Anton Starkopf and others, who he already knew from his studies in Tartu and Petersburg and who later became renowned innovators of Estonian art. His art studies in Paris were impeded by lack of economic means, which contributed to his focusing on literature. In Paris, Tassa also communicated with Friedebert Tuglas. He was active in the group Young Estonia, illustrated its publications and used it to publish his art criticism and fiction. He was also close with the Siuru group and a member of the Tarapita group.

When World War I broke, Tassa was mobilized and sent to serve in Petersburg and on the Turkish front in Erzurum. At the end of the war, he returned to Tartu where he helped found the art society Pallas and was its first director from 1918-1922. In 1919, he was also part of founding the art school Pallas and later worked there as a lecturer and teacher. From 1922-1923, he worked on founding the art department of the Estonian National Museum. From 1923-1924, he was a dramaturge at Vanemuine theater. From 1931-1940, he was director of the art and cultural history department of the Estonian National Museum. From 1928-1931 and 1940-1943, he worked at the Art Museum of Estonia in Tallinn. He died in Tallinn and is buried at Rahumäe cemetery in Tallinn.

Tassa was most active as an artist in the beginning of the 20th century until First World War, then fiction writing dominated his works in the second decade of the century. His first stories were published in Noor-Eesti magazine in 1911. After this, he published prose in journals. His only fiction books that were published in his lifetime are Nõiasõrmus. Fantastilised novellid (‘The Witch’s Ring. Fantastic Short Stories’, 1919) and Hõbelinik. Legendid (‘The Silver Doily. Legends’, 1921). After this, Tassa mostly focused on writing plays, the most famous of which is Kadaara sead (‘Gadarene Swine’, 1923). His last play Seitse magajat (‘Seven Sleepers’) was published in 1927, his next to last story Sügiskõnelused (‘Fall Conversations’) in the same year, and his last story Paabeli torni ehitamisel (‘Upon Building the Tower of Babel’) was published in 1944. A great deal of Tassa’s works remain as manuscripts. Sketches and fragments make up most of his manuscript legacy but there is also an unfinished novel, film scripts, numerous dream transcripts, etc.

Tassa’s stories and plays are dream-like as well with little dynamics and action – the main emphasis is on detail-rich descriptions of fantastic environments. Biblical and mythological motifs, that Tassa revises and shapes freely, have an important role in his literary works. The criticism of his two prose novels highlighted how different they were from the rest of Estonia’s literary scene. One of his most enthusiastic and approving critics was Friedebert Tuglas whose short stories somewhat resemble Tassa’s prose. The so-called true-to-life style of Estonian literature that became dominant in the late 1920s did not favor Tassa’s odd and extravagant fantasy. His prose has later been published in the books Saalomoni sõrmus (‘The Ring of Solomon’, Loomingu Raamatukogu, 1970) and Igaviku lõpul (‘In the End of Eternity’, 1989). The latter collection also contains thorough commentary on Tassa’s literary and art creations and the memoirs of his contemporaries.

S. V. (Translated by A. S.)

Books in Estonian

Stories

Nõiasõrmus. Fantastilised novellid. Kaas ja frontispiss: Ado Vabbe. Tartu: Odamees, 1919, 160 lk. [Sisu: ‘Merisõitjad’, ‘Enese ülistus’, ‘Saalomoni sõrmus’, ‘Laulvad kellad’, ‘Jalutussõit’, ‘Ilutulestus’, ‘Sügispäev’, ‘Põrgu aed’, ‘Surnu pärandus’, ‘Varemed’, ‘Suvitus mägedes’, ‘Lahkumine’, ‘Uneraamat’.]

Hõbelinik. Legendid. Kaas: Aleksander Grinev. Tallinn: Varrak, 1921, 105 lk. [Sisu: ‘Aheldud jumal’, ‘Tundmata jumal’, ‘Jutt nahaparkijast Athanaasiusest ja lõuendi värvijast Tiimonist’, ‘Jutt mungast, Maarja maalijast’, ‘Vaga Jaan’, ‘Kannatuse tee’, ‘Kolgata’, ‘Püütud kurat’, ‘Maria Magdaleena’, ‘Hää karjane’, ‘Äikse ilm’, ‘Igaviku lõpul’.]

Saalomoni sõrmus. Eessõna: Nigol Andresen. Tallinn: Perioodika, 1970, 166 lk.

Igaviku lõpul. Koostanud Mari Kõiv; eessõna: M. Kõiv ja E. Pihlak. Tallinn: Kunst, 1989, 174 lk. [Sisu: jutustus, novellid, reproduktsioonid kunstiteostest.]

Non-fiction

Puulõikekunstist. Materjale ja allikaid Eesti puulõikest XIX sajandil. Tallinn: Ilukirjandus ja Kunst, 1948, 88 lk.

Kivitrükikunstist. Materjale ja allikaid Eesti kivitrükist XIX sajandil. Tallinn: 1951, 297 lk.

About Aleksander Tassa

Igaviku lõpul. Koostanud Mari Kõiv; eessõna: M. Kõiv ja E. Pihlak. Tallinn: Kunst, 1989, 174 lk. [Sisu: jutustus, novellid, reproduktsioonid kunstiteostest.]