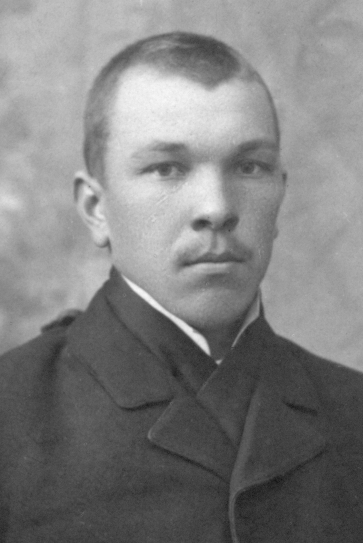

Jaan Oks

Jaan Oks (1884-1918) was an Estonian prose writer, poet and critic, whose sombre-toned works, with their spontaneous and sensitive imagery, are among the most original in Estonian literature. His texts, which mostly appeared posthumously, depict the inner life of a man against a depressing background, and his anxious attitude to his circumstances.

Jaan Oks was born in the village of Ratla in Pärsamaa parish on Saaremaa island, the son of a schoolteacher. From 1898 to 1902 he attended Kaarma teachers’ seminary, and after graduating from there, worked in Pühalepa village school on Hiiumaa. Having attended pedagogical courses in Haapsalu, he gained a qualification as a teacher in 1905, and worked as a teacher at Massu village school in Läänemaa county. Oks earned recognition for his liberal pedagogical activity, but his anti-Tsarist and anti-clerical stance and his opposition to manorial authority led to conflicts. In 1908 he moved to Samara governorate in Russia to work as a sacrist-schoolteacher for the Estonian community. In 1911 Oks was dismissed from his post, among other reasons because his intensive creative work was taking time away from his schoolteaching obligations. Work as a travelling salesman did not earn him enough income, and he became homeless, which led in turn to physical and mental exhaustion. In 1912 Oks was transported back to Saaremaa as a prisoner, and he lived there for a few years with relatives. When the war broke out, Oks was mobilized, but because of his poor health he was sent to the Tallinn district for fortification work. From 1917 Oks spent time in treatment in Tallinn hospitals. The diagnosis of bone tuberculosis came too late for treatment to help him, and Oks died at the age of 33.

Jaan Oks’ most intensive literary activity, the writing of short stories, poems, criticism and public commentaries, coincided with his time working at the Massu and Samara schools, from 1906 to 1909. It is not known how much Oks wrote, because despite his prolific creative output, very little of his work appeared in journals (including the Young Estonia albums) in his lifetime, and the majority of his manuscripts have disappeared. Some of his writings remained at the editing stage, and what was published appeared in heavily redacted form, since Oks’ style of writing was relatively strange for his time: his comments and criticisms were considered too harsh; his fiction was alienating in its unfamiliar style and subject matter. So Oks’ first book of prose, Tume inimeselaps (‘A Dark Child of Man’) only appeared after his death in 1918. In the course of time new manuscripts by Oks have come out, and so far the most complete collection of his works is Otsija metsas (‘The Seeker in the Forest’, 2003), containing 30 – 40 poems and about as many prose pieces. The collection Orjapojad (‘Sons of Slaves’, 2004) containing letters, articles and reviews of literature, presents Oks as a critic with powerful views and a broad knowledge of Estonian and foreign literature.

Oks’ earlier works – such as the stories Kolmekesi (‘The Three’), Isad ja pojad (‘Fathers and Sons’), Rõhutud ringides (‘Among the Oppressed’), were written in the typical “village realist” style of the time, at the centre of which is an unflinching confrontation with people’s miserable numbing everyday toil, mental poverty, narrow-mindedness and other depressing conditions. In the course of time the texts move further from realism; in his criticism, too, Oks expresses objections to the so-called “old” literature. Although in his more “modernist” texts there is still a sense of a context of miserable everyday life, what is more deserving of attention in them is the protagonists’ inner world, feelings, longings, physical sensations. Some of them take the form of a philosophical or associative train of thought, to which the author himself gives names, sometimes musical ones (such as ‘Passage’ or ‘Intermezzo’). Toward the end of his career Oks created more extreme works, such as Nimetu elajas (‘Nameless Beast’), Ihu (‘Flesh’) and Emased (‘Females’), of which the last two contain erotic imagery in a misogynistic tone. The long poem, or to give it the author’s name, the oratorio Kannatamine (‘Suffering’) mixes childhood memories with Biblical motifs. Oks’ vocabulary and syntax, with their Expressionist spirit, are unusual, spontaneous and vivid; at the same time some of his texts convey a pithful Symbolist system of imagery, such as the short story Tume inimeselaps (‘A Dark Child of Man’). Oks’ works are shot through with the idea of the inevitability of suffering; with his suggestive and sensitive imagery, it can be appreciated as a rebellion against this prospect.

I. S. (Translated by C. M.)

Books in Estonian

Short Stories

Tume inimeselaps: novellid. Tallinnas: Siuru, 1918. 77 lk.

Neljapäew: nowellid ja miniatüürid. Tallinnas: Auringo, 1920, 87 lk.

Hingemägede ääres. Tallinn: Eesti Raamat, 1989, 190 lk.

Emased. Meeleolu. Tallinn: Penikoorem, 1995, 61,[2] lk.

Ihu. Tallinn: Penikoorem, 1995, 22,[1] lk.

Poems

Kannatamine. Oratoorium. Tallinnas: Auringo. 1920, 60 lk.

Non-Fiction

Kriitilised tundmused. Esseed. Tallinnas: Siuru, 1918, 95 lk.

Selected and collected works

Kogutud teosed. Stockholm: Vaba Eesti, 1957, 313 lk. [Jutud, proosakatked, luuletused, kriitika, artiklid, kirjad.]

Teosed. Stockholm: Vaba Eesti, 1957, 231 lk. [Jutud, proosakatked, luuletused, kriitika.]

Vaevademaa. Tallinn: Perioodika, 1967, 196 lk. [Novellid, jutustused, esseed.]

Otsija metsas. Tartu: Ilmamaa, 2003, 438 lk. [Luuletused ja novellid.]

Orjapojad. Tartu: Ilmamaa, 2004, 420 lk. [Artiklid, esseed, kirjad.]