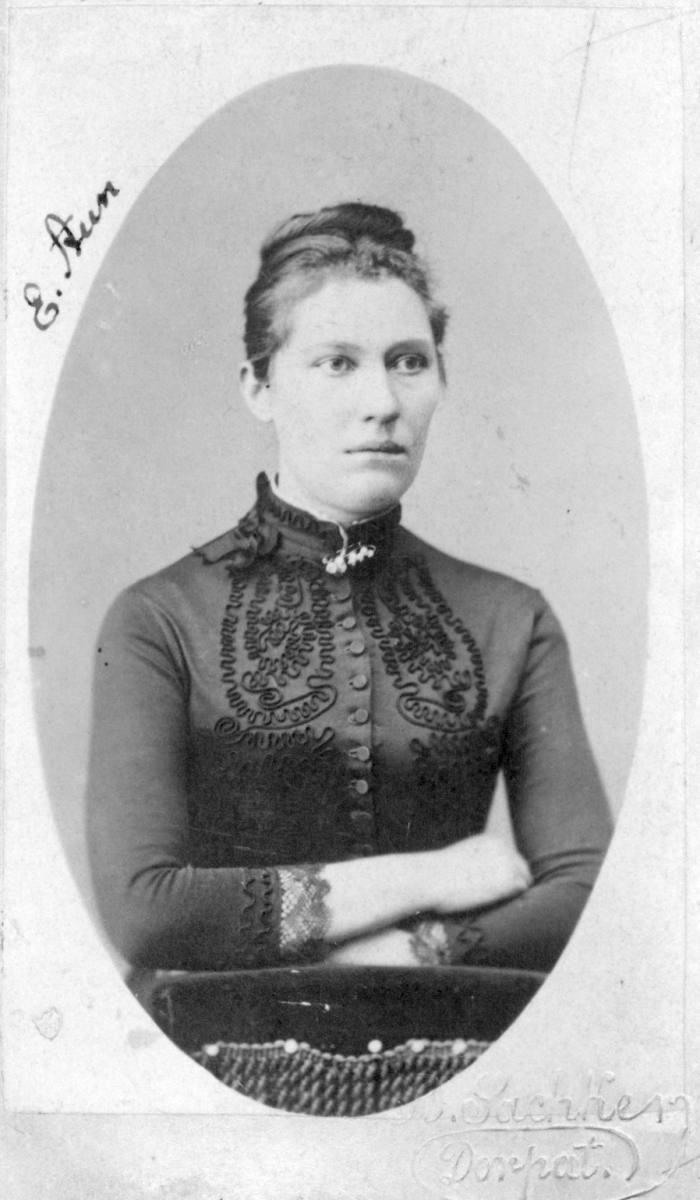

Elise Aun

Elise Aun (15. VI 1863 – 2. VI 1932) was a poet, one of the most eminent women writers of the end of the 19th century, whose works represent Estonian post-Romantic poetry. She also wrote prose.

Elise Rosalie Aun was born in Valgjärve parish in Võru County. She spent her childhood on the small manor of Ulitina rented by her parents in Setomaa (the culturally distinct region south-west of Lake Peipus which is shared by Estonia and Russia and inhabited by the Seto people who speak a variety of South Estonian). Given the lack of schools in the area, she initially received somewhat erratic private tuition; later, in 1882, she graduated from Räpina Parish Girls’ School in Lokuta village near Võõpsu. Unable to find steady work, she took on odd jobs in a number of places during the 1890s, living for a while at her brother’s home in Võtikvere village, then in Riga, Kronstadt, Valga and Pärnu. She also worked in the editorial office of the magazine Linda in Viljandi. In 1902 she became an outlet manager for the Christian Popular Literature Agency in Tallinn and got married in 1903. She lived with her family in Simbirsk (Russia) and Valga, where her husband was employed. In 1911 she moved back to Tallinn where she died in 1932.

Aun’s first poems appeared in the press in 1885, under the pseudonym “an Estonian girl from Seto land”. From 1880s–1890s some 200 of her poems were published in those newspapers and magazines that regularly published poetry at the time. Her first collection Kibuvitsa õied (‘Rosehip Blossoms’) came out in 1888, shortly followed by Laane linnuke (‘Forest Bird’) and Metsalilled ‘Forest Flowers’ (1890) and after a slightly longer break Kibuvitsa õied II (‘Rosehip Blossoms II’, 1895) and Kibuvitsa õied III (‘Rosehip Blossoms III’, 1901). The first three books were particularly well received and by 1890 Aun was widely known as a poet. Musical scores were written to several of her poems. After getting married, she practically stopped writing poetry.

The subject matter of Aun’s poetry remains within the characteristic boundaries of Estonian post-Romanticism, comprising nature, the home(land), love and other personal sentiments, all kinds of thoughts on and scenes from life, as well as religious themes and anniversaries. Consequently, there is an element of repetition in her poetry as well as features in common with her contemporaries, and yet she develops some essentially typical themes in an original and fresh manner. The poems about home, homesickness and homelessness stand out. It is evident that living in Setomaa the poet felt the benightedness of the region and wanted to escape to Estonia, the home of her people. Later, while living in different places, she missed the closeness to nature and the warm-heartedness of her Setomaa childhood home. Gradually she came to understand that she might be destined for enduring homelessness, a life on the road or abroad. The folkloric Koduta (‘Homeless’: “Nagu pääsu, päevalindu, / olen kulla koduta” // “Like the swallow, bird of the day / I have no sweet home”) is one of the Aun’s best known poems. A wistful sense of inevitability dominates in many of her poems, giving some idea of the struggles of a young woman aspiring to independence and at odds with her circumstances and surrounding prejudices. In general she captures mood with precise imagery, in a simple and measured, rather than ornate way that stands out from the typical post-Romantic manner of depiction. Her traditional verse form is elaborate and relatively diverse.

Aun has published a small collection Tosin jutukest (‘A Dozen Tales’, 1898) of sentimentally tinged fairy tales. Particularly noteworthy are two essayistic pieces on Setomaa, published in an 1888 issue of Postimees. Aun takes a stand against the derogatory attitude towards Setos, speaking warmly of their generous nature, cleanliness, handicraft, and singing tradition, but lamenting their illiteracy and almost non-existent formal education. Seto folklore collected by Aun is stored in the Estonian Folklore Archives. She has also translated a number of works of both prose and poetry.

E. S. (Translated by M. M.-K.)

Books in Estonian

Poems

Kibuwitsa õied. Tartu: H. Laakmann, 1888, 72 lk.

Laane linnuke. Tartu: K. A. Hermann, 1889, 82 lk.

Metsa-lilled. Oma sõpradele kimbuks köitnud Elise Aun. Tallinn: K. Busch, 1890, 91 lk.

Kibuwitsa õied. 2. jagu. Jurjev: K. A. Hermann, 1895, 64 lk.

Kibuwitsa õied. 3. jagu. Tallinn: J. Ploompuu, 1901, 88 lk.

Short stories

Tosin jutukesi. Jurjev: K. Sööt, 1898, 107 lk.