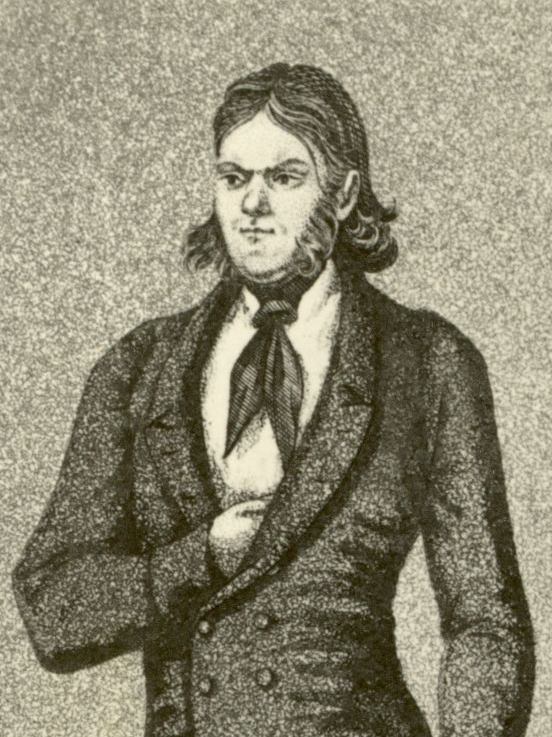

Kristian Jaak Peterson

Poems

Non-fiction

About Kristian Jaak Peterson

Kristian Jaak Peterson (Christian Jacob Petersohn, 14./2. III 1801 – 4. VIII / 23. VII 1822) was a poet and literary figure, one of the icons of Estonian culture.

He was born in Riga. His father, Jaak Peterson, was from Karula parish near Viljandi. His mother was Anna Elisabet (nee Mihhailovna). K. J. Peterson attended county school number 2 in Riga and from 1815 to 1818 the governorate gymnasium, and afterwards, from 1819 to 1820, Tartu University, initially in the faculty of theology, later in philosophy. He intended to continue his studies at the University of Leipzig. He died young of a lung disease (tuberculosis). The superintendent-general of Livonia, Karl Gottlob Sonntag, an influential figure in the church and education, wrote an obituary of his protégé.

The style of Peterson’s score or so of poems in Estonian is powerful and very rich in images. The frequent use of gerunds increases the elation of abstract concepts and the dynamism of the verb. His free and blank verse is fluent and original – with Peterson, real Estonian poetry and verbal art were born.

As a philologist he was very gifted, a polyglot, whose dream was to be a Christian missionary in America, Africa or Asia among indigenous people. In the spirit of Herder he was interested in both classical culture and the whole world’s vernacular languages, especially his own, Estonian. Even in secondary school he started writing poems and a diary of a philosophical and philological bent. In the Estophile Johann Heinrich Rosenplänter’s journal Beiträge zur genauern Kenntniss der ehstnischen Sprache he published articles on Estonian syntax, on the morphology of noun declensions and verb conjugations, phonetics and other issues. On leaving the university, Peterson gave language lessons in Riga and indulged in philology. He translated Christian Ganander’s Mythologia Fennica from Swedish into German, re-edited its contents and injected it with his own views on ancient Estonian beliefs, also mentioning Vanemuine and Kalevipoeg. Finnische Mythologie appeared as volume XIV of the Beiträge (1821/1822). His legacy in manuscript passed by way of Rosenplänter into the hands of the Estonian Learned Society; a century later it was made public and evaluated on the initiative of Gustav Suits of the Young Estonia movement.

Peterson, who called himself ‘the bard of the land folk’ (maarahva laulik, that is, the Estonian poet) valued both classical greatness and vernacular originality in literature, as was the fashion in Europe then. He knew well Pindar’s odes, Theocritus’ bucolics and idylls, Virgil’s pastorals, Horace’s lyrics and the Bacchants’ Anacreon. He received strong influences from the pre-Romantic poetry of F.G. Klopstock, J.W. Goethe and F.M. Franzén; he read folk poetry through Herder, and heard it from the mouth of his father Kikka Jaak. In philosophy, Peterson’ s model was Diogenes’ stoicism and cynicism, and the dualistic deism of Christian Wolff, a proponent of Leibniz’ system. The rationalism of Wolff was followed by Peterson’s favourite professor in Tartu, the theologian and Orientalist Friedrich Hezel, who was also an expert on Pindar. The Supreme God is the beginning and end of all existence. This being arranges matter (in Peterson’s expression, ema-asi – ‘the mother-thing’ or ‘maternal stuff’) and emanates downward like a powerful waterfall or dew; spirit-filled people seek love in each other and strive in their turn to rise up back to God on the laulutuul ‘the wind of song’.

Corresponding to these spheres, Peterson creates odes in a high style, originating from heavenly measures and classical aesthetics, and spiritual love between friends: the hymns Jummalale (‘To God’), Päva loja-minnemine (‘The Setting of the Sun’), Süggise (‘Autumn’), Innimenne (‘Human’), Kuu (‘The Moon’), Sõbradus (‘Friendship’), Lotus (‘Hope’), Olen jälle õnnis (‘I am blessed again’), Rõmolaul (‘Song of Joy’), Laulja (‘The Singer’). His pastorals, however, exhibit a low and occasionally more comic style, concerned with earthly things and examples from folk-songs, as well as warm earthly love for girls: Karjaste-laul. Elts ja Tio, karjatsed (‘Song of the herd-girls. Elts and Tio, the shepherdesses’), Jaak, Jürri – karjapoisid (‘Jaak, Jüri – the herd-boys’), Karjaste laul. Ot ning Pedo (‘Song of the Herdsmen. Ott and Pedo’); Ma pean joma. Lauloke (‘I have to drink: a little song’), Naesed (‘Women’), Allo ning Jaak. Karjaste laul (‘Allo and Jaak. Herdsmen’s song’), En ning Ello, karjaste laul (‘Enn and Elo, a herdspeople’s song’), Minno issa ütleb et öpik laulab nenda (‘My father says the nightingale sings like this’). Some texts in a median style exist as a circular movement between the eternal heavenly one and the level of time and space, in which the sublime intertwines with the personal: Laul, kui ma Tartust läksin Ria pole, omma vannemad vaatama… (‘Song of when I went from Tartu to Riga to see my parents’), Jago-laul. Ta istub üksi mäe peäl (‘Song of Jaak. He sits alone on a hill’), Mardi Lutteruse päval (‘On Martin Luther’s Day’). In 1823 three of Peterson’s poems in German appeared posthumously (including one sonnet) in the journal Zeitung für die elegante Welt (translated into Estonian by Betti Alver in 1961).

Peterson is remembered in a memorial stone at his father Kikka’s farm in Viljandimaa county, on a memorial tablet in a high school building in Riga, and a mighty monument on Toomemäe Hill in Tartu (sculptor Jaak Soans, architect Allan Murdmaa, 1983). There is a Kristjan Jaak Peterson Secondary School in Tartu. Since 1996 the poet’s birthday, 14th March, has been celebrated in Estonia as the national Mother Tongue Day.

A. M. (Translated by C. M.)

Books in Estonian

Laulud, päevaraamat ja kirjad. Korraldanud ja redigeerinud Aino Paltser. Tartu: Eesti Kirjanduse Seltsi koolikirjanduse toimkond, 1922, 189 lk.

Laulud; Päevaraamat. Redigeerinud ja eessõna: Karl Taev. Tallinn: Eesti Raamat, 1976, 128 lk.

IAAK: Kristian Jaak Peterson 200 = IAAK: Kristian Jaak Peterson: aus Anlass seines 200. Geburtstages. Toimetanud Urmas Sutrop, Kristiina Ross, Jaan Undusk jt (Eesti Keele Instituut ning Underi ja Tuglase Kirjanduskeskus). Eessõna: Urmas Sutrop. Tallinn: Eesti Keele Sihtasutus, 2001, 425 lk. [Includes the original texts of Peterson’s two poetry collections and the diary, the glossary of those works, his all known linguistical articles in German and their Estonian translations, and overview of his life, work and reception. The book also contains German translations of 10 Peterson’s odes and three poems written in German.]