New Caledonia on Its Way to Independence: Third Times’s the Charm?

On 12 July 1998, Christian Karembeu added a FIFA World Cup trophy to his already impressive collection of awards. He was part of France’s winning team, which included several players from the former French colonial empire, and some of them, such as Patrick Vieira and Lilian Thuram were more well-known than Karembeu. However, Karembeu was one that was criticised for not singing La Marseillaise. 67 years earlier, in 1931, several people were exhibited on the Paris Colonial Exposition as savages, ‘cannibals,’ and were later exchanged for crocodiles with the Weimar Republic – one of those people was Christian Karembeu’s great-grandfather. Karembeu, of Kanak origin, came from New Caledonia. Due to this atrocity, he refused to participate in a symbolic act that most international footballers do.

![]()

Image: Christian Karembeu, a former professional footballer who is currently the Strategic Advisor for Olympiacos (Source: Iconsport).

In the same year as the French World Cup victory, an accord was signed in the New Caledonian capital in May and was ratified through a referendum on the archipelago in November. It was the Nouméa Accord that had France, the independence-supporting Front de Libération Nationale Kanak et Socialiste (FLNKS), and anti-independence party Rassemblement Pour la Calédonie dans la République (RPCR) as signatories. The agreement was designed to decolonise the Pacific nation by proposing three referendums of independence from 2018 to 2022. There were to be only three referenda in the case if the first (or the second thereafter) would reject independence and maintain ties with metropolitan France.

The Nouméa Accord was the final treaty in a series of actions mostly from the side of the French government to increase the autonomy of New Caledonia. Some of these, such as the land distribution plan in mid-1980s, did not go down too well with the Kanak population. Although the events of 1931 remain firmly in historical memory and were not to be repeated later, violence erupted in 1980s between the Kanaks and European settlers. Today, the UN considers New Caledonia to be one of 17 extant non-self-governing territories where decolonisation has not been completed.

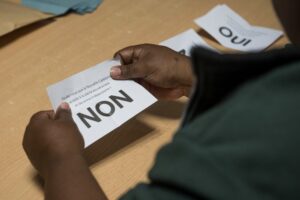

Kanaks make up around 40 percent of the around 270,000 inhabitants of the archipelago. European settlers and their descendant around one third and the rest are from Asia and other Pacific islands. As one would expect, the Kanaks are more pro-independence and Europeans more pro-France. Moreover, two of the three referendums have been conducted, including one last Sunday, 4October. The first of those was done 20 years after the Nouméa Accord in 2018. As the second one was necessary, one already knows that pro-independence side has already lost the vote. With a turnout of 81 percent, the ‘Yes’ side managed to garner a 43.3 percent of votes cast while those supporting ‘No’ captured 56.7 percent of the vote. This year’s referendum had a slightly higher turnout with 85 percent, and the difference between ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ on the issue of independence has decreased to 46.7 percent and 53.3 percent respectively. As a result, there will be another popular vote in 2022.

Image: This time, ‘No’-votes prevailed (Source: AP Photo/Mathurin Derel)

What would be the most pressing issues associated with independence? First, there are social divisions among the islanders. As stated above, the Kanaks are more pro-independence and the Europeans more pro-France. Both French president Emmanuel Macron and President of the Government of New Caledonia Thierry Santa stressed that there are divisions in the society, and these must be overcome by looking to the future. As the margin between ‘Yes’- and ‘No’-votes has decreased, there is a chance that the third referendum in two years’ time might produce an independent New Caledonia. However, the social divide will remain. Hence, this is an issue that the Pacific nation faces whatever their political status will be.

Secondly, as with most questions of independence, there is a central one about the economy. Here, we can also see two sides. First, according to the CIA World Factbook, New Caledonia has second largest reserves of nickel, 11 percent of world’s total. Nickel is New Caledonia’s main export good, shipped to China, Japan, and South Korea. Full control over these reserves would be an incentive for independence. Conversely, a sum equal to around 15 percent of the GDP is annually received from France. That would probably be lost over time and must be somehow compensated.

On the political side, the archipelago is “seen by France as a strategic political and economic asset in the region.” Indeed, it gives France a position in South Pacific and would help to counterbalance Chinese influence. In case of independence, this leverage would be if not lost then severely weakened for France. China is the main trading partner of New Caledonia and plans to invest in the French holdings in the Pacific, and hence, it could wield political influence. Similar trends can be observed in French Polynesia, another overseas territory. While not to the point of conducting referendums, the independence movement in French Polynesia is not absent either. French Polynesia is also a UN non-self-governing territory, therefore open to a decolonisation process. However, it would be in French interest to keep these collectivities linked to metropolitan France.

Overall, it remains to be seen how the results of the third New Caledonian referendum will be. Two years may bring about a necessary shift in favour of pro-independence camp. If they win, then another major issue will arise – i.e., a ‘divorce agreement.’ These questions are never easy. However, will New Caledonia become another de facto state? Most likely not.

Author: Raul Toomla