In the Midst of Conflict: Reassessing the Future of the Gaza Strip

The ongoing war in Israel and the Gaza Strip is threatening the fragile stability of the entire region. The potential involvement of Hezbollah and Lebanon, rockets being fired into the south of Israel from the Yemen, and the blatant involvement of Iran in fermenting, and backing, the violence and terror taking place, does not bode well for the immediate future. At the same time, the relative silence of the other major players in the Middle East – Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States – along with the fact that they have not broken their formal relationships with Israel, is a clear indication of the way in which regional geopolitics has undergone significant change over the past few years.

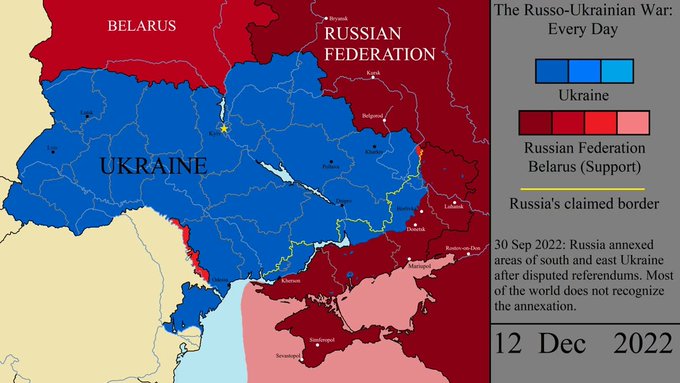

Gaza is but a snippet of territory. No larger than 365 sq. kms, with a rapidly growing population of approximately two million residents, makes it one of the most densely crowded micro territorial units on the world’s surface. It’s formation over time, the influx of refugees, especially in 1948 and again in 1967, and it’s almost total territorial enclosure by Israel (to the east and north), by Egypt (to the south along what is known as the Philadelphi Line) and, again, by Israel in its maritime waters, has resulted in major obstacles to any normal type of development – even if there was a normal system of civil and democratic government, which there is not.

Image: The Borders of the Gaza Strip

When Israel withdrew from the Gaza Strip in 2005, and dismantled the Jewish settlement network, handing over much of the existing infrastructure to the Palestinian Authority, there was a significant public opinion majority inside Israel for this move. It was believed, at the time, that the development of the Gaza Strip under Palestinian rule, as a form of microstate in all but name, would serve as an indication to what may potentially be the next stage of withdrawal in parts of the West Bank. But the democratic election of a Hamas-based government, along with increased radicalization and the transformation of the territory into a base for missile attacks into Israel, resulting in a sequence of mini wars and retaliations, proved to be contrary to all expectations, culminating in the current war which began with the Hamas attacks and incursions into Israel on October 7th 2023.

This also resulted in a significant change in Israeli public opinion concerning the possibility of further withdrawals and an eventual Two State solution to the ongoing Israel – Palestine conflict, with the left moving into the centre, the centre to the right, and the moderate right to the extreme right, resulting in the election of the most extreme right-wing government in Israel’s history, totally opposed to territorial withdrawals or Palestinian statehood, in the elections of 2022.

Questioning Israeli security and defence doctrines

The events of 7th October have raised many questions about some long held Israeli security and defence doctrines. In the first place, there was a clear failure of the Israeli intelligence services, normally considered to be amongst the best in the world, in their lack of knowledge about the Hamas attack along the entire border and with the infiltration of approximately 3000 terrorists through the border which was considered to be highly fortified and virtually impenetrable.

Secondly, the underlying assumption that because of the highly fortified border, there could not be any significant movement from the Gaza Strip into Israel, other than through the approved crossing points, resulted in the transfer of most land forces away from the region, many of them into the West Bank to provide additional security for the Israeli settlement network in this region. Thus, following the incursion into the Israeli settlements on the Israeli side of the border, it took almost ten hours for the troops to be redeployed, during which time most of killings and destruction of the communities took place.

The events of 7th October have also raised serious questions concerning the effectiveness of physical borders in providing the necessary security and defence objectives. Although the increase in indiscriminate missile attacks from Gaza into the neighbouring Israeli towns and rural communities has been on the increase during the past decade, this has largely been dealt with by the iron dome anti-missile ballistic system, which has succeeded in detecting, within seconds, the firing of missiles and, where necessary (where they are deemed to be headed for towns rather than empty spaces) have brought them down in mid-air. The iron dome system has had a high success rate, while future modifications, notably the completion of a laser anti-missile system, which, according to news reports, would be operational in about two years from now, would enable an even more accurate and speedy response to numerous missiles being fired into Israel.

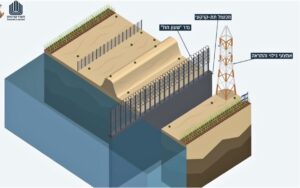

The construction of tunnels under the Israel-Gaza border, enabling terrorist groups to enter Israel and the neighbouring communities, had been brought to an end by the construction of a concrete wall almost twenty meters below ground along the entire length of the border, thus creating what was described as an iron fortress. The idea that terrorist groups would simply break through the existing fence and walls encompassing the Gaza Strip was not considered realistic and this largely explains the lack of Israeli troops at any point along the entire border and their redeployment elsewhere.

Image: The Undergound Wall Barrier between Israel and the Gaza Strip (Source: Israel Defence Ministry – Public Access)

But in recent years the multi billion dollar border fortifications have been challenged through much cheaper and simpler means. The attachment of incendiary devices to simple balloons, waiting for the wind to blow in the right direction and crossing the border and setting fire to the crops of those communities in close proximity to the border has proved to be effective, as has the use of 100 dollar drones or, as used on 7th October, hang gliders to cross the border (Figs 3a and 3b). None of this requires multi billion dollar investment and has proved to overcome even some of the most sophisticated and securitized border installations on the face of the globe. An eventual withdrawal of Israeli troops from the Gaza Strip and a return to border management and control, will have to take these factors into account if and when the Israeli troops withdraw from the Gaza Strip.

Image: Breaching the Wall – Balloons (Source: Hamodia Newspaper)

Image: Breaching the Wall – Tractors (Source: Ynet News)

Future prospects and uncertainties

It is difficult to write about the future of the Gaza Strip when the war is continuing and there is no realistic vision of this war, despite the current limited ceasefire for the purpose of limited return of kidnapped civilians and hostages (women and children in the first stages), finishing in the near future. But at one point in time, the armed conflict will cease and much thought will have to be given, yet again, to the redevelopment and reconstruction of the entire region, and the political forms of control and administration which will be acceptable to all sides.

Public opinion in Israel, excepting the far right, will not agree to any long-term military occupation or administration of the Gaza Strip and, sooner or later, the troops – having damaged or perhaps destroyed altogether, the Hamas military capabilities, will have to withdraw back into Israel. At the same time, Israel will not agree to any form of Hamas (or other similar) control regime, while the Palestinians will not agree to any form of control or administration in which Israel has a direct role. The suggestion that the more moderate (sic) Palestinian Authority which, at the time of writing, still controls the West Bank autonomy areas, would take control, seems unlikely given their internal weakness and the fact that this would appear to run contrary to the wishes of the Gaza Palestinian population.

Some form of regional or international administration would have to meet the demands of both sides and, based on past instances of such external administration – especially on the part of the United Nations – in this part of the world, could fall apart very quickly. The international peace forces in the Sinai peninsula, upholding the Israel-Egypt peace, is an American led international force, which would almost certainly be rejected by the Palestinians and their external supporters such as the new Iran – China – Russia axis, while a United nations (perhaps along with an EU) temporary administration would have to prove that it has the teeth to prevent the return of Hamas (or similar organization) from gradually returning to power – something which previous UN forces have proved to be incapable in the face of local pressures.

Gaza’s immediate neighbour to the south, Egypt, is not interested in being directly involved. From 1948-1967, Egypt administered the Gaza Strip, much the same way that Jordan administered the West Bank. But it was a harsh administration and is not remembered in a positive way by the local inhabitants. At future junctures, when Israel signed the Oslo Accords in the early 1990’s with the Palestinians, or when Israel withdrew from the Gaza Strip in 2005, Egypt made it clear that they were not interested in becoming involved, other than maintaining their tight control over the Philadelphi line border between their respective territories. This has been a closed and strongly fortified border for most of the period since 2005 (tunnels withstanding) and it took over a month of fighting in the present conflict, until Egypt eventually opened the border crossing to allow foreign nationals and injured civilians to cross from Gaza into Egypt.

Image: The Philadelphi Line between Egypt and the Gaza Strip (Source: Unknown)

Image: The Philadelphi Line Fortified Border between Egypt and the Gaza Strip (Source: Al-Monitor)

In the past there was talk about the need to enlarge the territorial base of the Gaza Strip. When the immediate post-Oslo discussions talked about the potential establishment of a Palestinian State, this included the possibility of land swaps between Israel and the Palestinian Authority in order to enable many Israeli settlements (I the West Bank) to remain in situ, with the Palestinians being compensated for land elsewhere in and around the Green Line Border, in areas of relatively sparse, or no, settlement inside Israel. This, it should be noted, was at a time when the Israeli settlement population in the West Bank numbered almost half (250,000) of what it numbers today (over half a million).

One proposal envisaged that land for a Palestinian State would be appended to the Gaza Strip, inside Israel immediately along the Israel-Egypt border and additional land inside Egypt, thus enabling the Gaza region of the Palestinian State to have sufficient land on which to expand and develop. But this idea was never taken further as the post Oslo negotiations eventually collapsed during what was meant to have been a five-year interim period in which all outstanding issues – Israeli settlements, refugees, Jerusalem, water geopolitics etc; – were to be resolved. In reality, this period, during which Israeli Prime Minister Yitzchak Rabin was assassinated by a right-wing extremist, and in which radical peace spoilers intervened, brought an end to any further negotiations and the eventual death of the Oslo Accords.

One of the outstanding territorial problems relating to any future Palestinian State concerns the link or connection between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, assuming that they remain part of a single political authority. In the post Oslo period, three safe passage routes had been envisaged, two of which operated for a period of time (the third which would have required going via Jerusalem, was rejected by Israel). There is no way that an uninterrupted territorial link between the two regions could have been created as this would have necessitated a breach in Israel’s territorial integrity and continuity.

The main issue was one of administration and control and the right of Israel to check the passage of people and goods on a daily basis. But for as long as the Oslo Accords held up, and prior to the construction of the wall and fence around the West Bank, this arrangement held up with few problems. Such a connection is necessary as it enables greater employment and educational opportunities for Palestinians of the Gaza Strip in the West Bank, and access to a seaport on the Mediterranean Sea for an otherwise landlocked West Bank. Whether such a link would be possible under a future arrangement depends greatly on the political administration and the ability of what is today a very weak Palestinian Authority to take back control of the Gaza Strip in what could potentially be a post-Hamas era.

A huge amount of investment into the reconstruction of much of the Gaza Strip (at the time of writing the almost complete destruction of the northern area of the Strip where the fighting is taking place) would also have to ensure, this time round, that international aid – be it from the UN, the EU or Qatar, would really go into the development of housing and civil institutions, and not into the strengthening of any military capabilities, or new systems of underground tunnels – an underground city below the whole of Gaza. This would require a strong international presence and, as indicated above, it is not clear where this would come from at this present time. The idea that Gaza could yet develop into the Singapore of the Middle East is a nice slogan but which unfortunately, is no more than a dream and a vision which has almost no possibility of being implemented.

The fact that the present Israeli government, formally in an ongoing state of war with Hamas, has no clear exit route from this war, would indicate that any future political territorial arrangement for the Gaza Strip, as a self-controlling entity or micro microstate, is yet to be clarified. The present situation of instability is likely to continue for some time, well into 2024 and perhaps even 2025, as the region faces a very uncertain future.

Author: David Newman