Conflict and Copper: The Path to Bougainville’s Independence Referendum

On December 11, Bougainville, a semi-autonomous group of islands, voted overwhelmingly for independence from Papua New Guinea.

If you’re scratching your head wondering where Bougainville is, and why this vote has significant social, economic, and political implications, you aren’t, necessarily, alone. As a little-known region of a nation shrouded in mysticism and speculation, Bougainville—its conflict, struggle for freedom, and perhaps even existence—is often forgotten. This is, of course, a mistake. Rich in cultural (and political) history, Bougainville is an important place for both academic research and personal interest.

|

Bougainville Cheat Sheet

|

Francis Ona– Bougainville secessionist leader, de facto president, and self-anointed king of the Republic of Me’ekamui (an indigenous name for Bougainville)— stated, in the 2001 documentary about the Bougainville fight for independence The Coconut Revolution, “We are fighting for man and his culture…land and environment… independence.” Truly, Bougainville—its quest for identity and self-determination—can be understood in these terms.

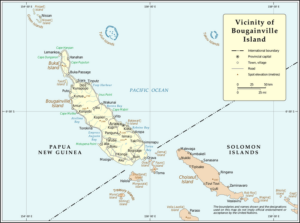

Man and His Culture: diversity, colonial borders, and a uniting cause

Bougainville’s recent history is dominated by an overwhelming colonial narrative, repeated across the globe, where colonial powers drew lines and struck divisions based on their own power struggles with little regard to the people ‘under’ their flag. Carved into German, British, Japanese, and Australian territory, Bougainville’s connection to Papua New Guinea (PNG) is a remnant of a colonial past rather than an ethnic, geographic, linguistic, or cultural connection. Bougainville is incredibly diverse; however, their closest relatives are the Solomon Islands, rather than PNG. In fact, at their closest point, Bougainville and islands within the Solomon Island nation are mere kilometers apart.

Bougainville, itself, is ethnically, linguistically, and culturally diverse. What united a sense of ‘Bougainville,’ or a collective consciousness, ultimately, was copper. Indeed, invariably flecked throughout Bougainville’s struggle for independence is copper’s metallic sheen. Discovered on the island in the 1960s, copper, the worlds’ most used metal, has (in many ways) directed Bougainville’s path to sovereignty.

Land and Environment: copper, exploitation, and ‘the world’s first eco-revolution?’

In the early 1970s, Rio Tinto, an Australian-British mining company capitalized on Bougainville’s copper (and other metal) resources and established the world’s largest open cut mine in Panguna. Rio Tinto, one of the largest mining conglomerates in the world, began pumping resources out of Bougainville in 1972.

The early 1970s were a transformative time for Bougainville. Beyond the establishment of the Panguna mine, the early 1970s saw Bougainville attempt to gain independence for the first time in a unilateral, and largely ignored, declaration two weeks prior to PNG independence from Australia. Involuntarily integrated into the newly formed PNG, Bougainville financially supported the fledgling state with the Panguna mine. In fact, some estimates claim Bougainville’s mine was responsible for ~45% of PNG’s GDP. But, as resources left the island, leaving behind trails of chemical pollutants and marred land, Bougainville islanders saw little profit. Land, taken by force to establish the Panguna mine, produced over 3 billion USD of profit; however, Bougainville islanders only received around 1000 USD of payment. In 1988, under increasing frustration over the degradation of Bougainville and money leaving the island, some islanders (under the leadership of Francis Ona) collectivized and produced a set of demands, ultimately unanswered by the mine. Activists decided to close the mine themselves, an action met with armed response by PNG forces (supported by Australia). Thus, began the Coconut Revolution, dubbed the world’s first ‘eco-revolution.’

The conflict, the “longest and bloodiest conflict in the Pacific since World War Two” lasted nearly 10 years. Bougainville, severely ill equipped to combat PNG and Australia, suffered immensely. Conflict violence and an Australian naval blockade contributed to the death of approximately 20,000 people, or about a 10th of the island’s population. Peace, arbitrated by international actors including New Zealand, came in 1997, with agreements finalized in 2001. Part of the peace agreement was Bougainville’s status as an autonomous region of PNG and the stipulation that Bougainville would have an independence referendum before 2020. Thus, in the final hours of 2019, Bougainville was finally able to vote for peace.

Independence: a long-awaited referendum

Bougainville was finally able to vote for independence in early December. In a process that took over two weeks (in order to access even the most remote areas) the referendum, overseen by former Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern, is generally considered to have been a good democratic exercise. But, beyond a democratic exercise, Bougainville’s independence referendum represents a massive psychological relief. Voting envoys were met with traditional dancing, song, and a general spirit of celebration. As John Momis, president of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville stated: “Now, at least psychologically, we feel liberated.” Bougainville voted overwhelmingly for independence, almost 98% (176,928 people) voted for independence.

Although Bougainville’s historic vote for independence can be seen as little else than a mandate for self-determination. Bougainville’s independence vote, however, was non-binding. This means independence will have to be negotiated with PNG, a nation wary of setting a precedent for other provinces. PNG receptions to Bougainville’s vote have almost all included an allusion to a lengthy process, directed by PNG. Puka Temu, PNG minister for Bougainville affairs, acknowledged the vote, but implored voters to “allow the rest of Papua New Guinea sufficient time to absorb this result.” PNG Prime Minister James Marape, largely considered to be a conciliatory leader focused on unity, accepted the referendum result but claimed PNG will develop “a road map that leads to a lasting peace settlement,” a vague epithet with various implications, all of which are ambiguous.

Some Bougainville observers predicted settlement processes will take over ten years, and will require Bougainville to demonstrate economic viability, which most likely means the re-opening of the Panguna mine. The Panguna mine, valued at over 58 Billion USD, would have (and already has) disastrous implications on the environment of Bougainville. Its re-opening has especially become attractive to foreign investors, including China—a nation keen to exert influence in the Pacific.

Only time will tell what happens next to Bougainville. It is clear, however, that Bougainville post-conflict is searching for self-determination and lasting peace.

Author: Annie Rose Healion