Complete Separation Is Not What Transnistrians Voted for in 1989-1990

When I started my PhD almost 4 years ago, I wanted to explore the internal dynamics of Transnistria’s secession movement. From what I had read up to that point, it was clear that Russia’s involvement in the conflict had been well covered. So too had the disputes between elites in Chisinau and Tiraspol. But the de facto state of Transnistria contains six other administrative regions (Camenca, Rîbnița, Dubăsari, Grigoriopol, Bender, and Slobozia). When I began, I wanted to understand how the inhabitants of these regions viewed the secessionist movement.

I was also interested in whether anyone in the region tried to resist secession. From the literature I had read, this question was rarely addressed, with some even claiming there was no resistance. This surprised me because Moldovans accounted for around 40% of the population at the time and achieving 100% consensus on any topic is almost impossible.

I fixed my dates between 1989, when the Union of Joint Labour Collectives (OSTK) was formed (see below), and 1992, when the Transnistria gained de facto independence. During the course of my research, I worked in repositories in Moldova and Transnistria. In Moldova, I worked in two archives, the Archive of Social and Political Organisations of Moldova and the National Archive, which both housed documents that explained the conflict from Chisinau’s perspective.

The National Library was a particularly valuable repository. Here, I consulted over thirty different newspapers, including the Republican Press, local newspapers published in all seven of Transnistria’s districts, as well as periodicals published in large enterprises. In order to understand how elites from elsewhere in Moldova reacted to the collapse of the Soviet Union, newspapers from Moldova’s other predominantly Russian-speaking regions (such as Taraclia and Bălți) were consulted. This research was particularly valuable, as it highlighted the shortcomings of the local communist parties in Transnistria and explained why the OSTK could seize power.

In Transnistria, the archival service is decentralised, which means that if one wants to work with documents pertaining to each district, they must travel to each regional archive. This is a time-consuming process. However, it was extremely rewarding. Most archivists had never had a foreign researcher in their archive, so my presence was well received. So much so, in fact, that directors from local museums also came to visit me and gave me access to their collections, some of which were not on display to the public.

Image: “Chronicle of the Strike” – a broadsheet published by the OSTK branch in the city of Rîbnița, which is impossible to find outside of Transnistria (Source: Keith Harrington)

.

This extensive primary research revealed a new side to the Transnistrian conflict that had not yet been covered, where industrial elites vied for power in their cities, then rural Moldovans struggled to remain part of their parent state. It is, of course, impossible to summarise all of my findings in this blog post. However, there are two points in particular that are worthy of attention. First, that support for Transnistrian secession was not as widespread as previously thought. Second, that much of the opposition to secession manifested itself along ethnic lines, with rural Moldovans, in particular, wishing to remain part of their parent state.

Since its inception, the de facto state of Transnistria has stylised itself as democratic and inclusive. This can be traced back to 1989 when a dispute emerged between industrial elites in Transnistria, represented by the OSTK, and the Moldovan Supreme Soviet. The OSTK was critical of the Supreme Soviets’ decision to adopt language laws that made Moldovan the republic’s sole official language without holding a nationwide referendum. In response, the OSTK proclaimed that all serious matters should be decided by referendum. This has been a guiding principle of Transnistrian politics ever since. The region has organised several referendums since achieving de facto independence, and article 62.2.E of the constitution proclaims that a referendum should be organised on the most important issues.

This is something that political elites are immensely proud of. In 2018, President Vadim Krasnoselsky stated that referendums were held across the region before the creation of the Transnistrian Moldovan SSR. Krasnoselsky noted that the people of Transnistria voted to join the TMSSR, while the people of Moldova had not been given the opportunity to vote on their own independence. However, this statement was not entirely accurate. On 2 September 1990, elites from all over Transnistria gathered to proclaim the creation of the TMSSR, which was made up mostly of the territories controlled by the separatists today. In their statements, the deputies proclaimed that they were enacting the will of their people, who had voted on the issue between 1989-1990. They also claimed that the TMSSR would be an inclusive republic that would respect the rights and opinions of its citizens. However, the TMSSR contained several regions that had refused to organise a referendum.

On 1 July 1990, the city of Bender organised a referendum. However, the village of Varniţa, which was administered by the city, did not participate. A few weeks later, the district authorities in Camenca passed a law that forbade the organisation of a referendum on their territory. In Slobozia, the district authorities refused to sponsor a referendum. Instead, referendums were organised on the initiative of local elites in a few select villages between July and August. On 10 August 1990, the city of Dubăsari organised its own referendum. In contrast, the district authorities refused to participate and effectively severed ties with the city over their separatist tendencies. Finally, in Grigoriopol, voting did not take place until 9 September, five days after the TMSSR had already been created, and even then, six villages refused to participate in the voting.

Despite their refusal to organise referendums, these regions were incorporated into the TMSSR. Moreover, those who participated in the voting in Rîbnița, Tiraspol, Bender, Dubăsari city, and certain villages in Slobozia and Grigoriopol, never voted for the creation of the TMSSR. In these referendums, residents were asked whether they supported the creation of the Transnistrian Moldovan Autonomous SSR. While most would have likely voted for complete separation, it is not what they voted for.

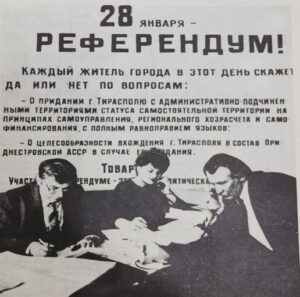

Image: An advertisement for Tiraspol’s Referendum in the newspaper Dniestrovskaya Pravda. Note how it states ‘Transnistrian ASSR’ (Source: Keith Harrington)

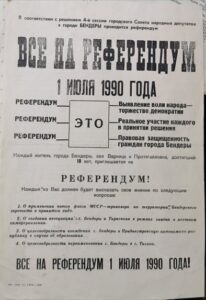

Image: A flyer promoting the referendum in Bender. Note how point 3 states ‘Transnistrian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic’ (Source: Keith Harrington).

These brief examples demonstrate a few important things. Firstly, willingness to participate in Transnistria’s secession project was not unanimous, as is often assumed. Moreover, while scholars have typically argued otherwise, there was a clear ethnic dimension to the conflict. The regions listed above that refused to participate in the referendums were some of the most ethnically homogenous regions of Transnistria. For example, in the Dubăsari district Moldovans accounted for 89% of the population, in Varniţa they accounted for 80%, and in Butor and Mălăiești (2 communes from Grigoriopol) they made up over 95% of the local population. This was not the only time those regions expressed support for the parent state. As I demonstrate in my thesis, they supported the 1989 language laws, flew the Moldovan tricolour in 1990 (which the OSTK labelled a fascist symbol), and organised demonstrations against secession after the Second Congress.

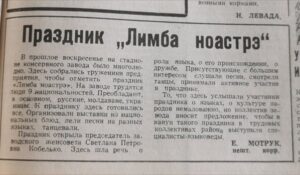

Image: Celebrating “Limba Noastra” in Camenca. The holiday commemorates the passing of the 1989 language laws. In the industrial cities of Transnistria, the day was not celebrated, but sparked protests. The article appeared in the local newspaper Dniester (Source: Keith Harrington)

Not all Transnistrian Moldovans opposed secession. On the contrary, most of those in the industrial cities supported it. However, like anywhere else, intragroup preferences vary. I argue that due to a range of factors, those in the regions that opposed secession tended to have a stronger sense of ethnic identity and connection with the parent state than those in the cities. Furthermore, it should also be acknowledged that there were pro-Moldovan groups active in the industrial cities, even in the de facto capital of Tiraspol. To summarise, the extensive primary research that I have conducted over the past few years confirms my initial assumptions: that the Transnistrian conflict was far more dynamic than previously thought.

Author: Keith Harrington