Neglect Disguised as Peace: The “Peace Agenda” and the Armenian Parliamentary Elections in June 2026

In June 2025, the Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan claimed, “We didn’t lose Nagorno Karabakh, we found the Republic of Armenia.” He even went further to argue that the Nagorno-Karabakh issue has been used as a “leash” for years to prevent Armenia from developing. Setting aside the normative impulses and questions regarding the truthfulness of PM’s claims, let us examine the Republic of Armenia we “found” after the “leash” was violently removed, as the 2026 parliamentary elections approach. While I am writing this piece, the Armenian social media is flooded by images and information on major wildfires in the country’s North-East and reports of unhealthy air quality in Yerevan that is far above WHO limits.

As the firefighters, police officers and forestry workers were putting their lives in line to put out the wildfires, the Yerevan mayor (who last year said the independent reports of Yerevan’s air pollution are fake) calmly blames the poor air quality of the city on “seasonal and geographic peculiarities,” seasonal heating, fires, burning leaves and dust (dismissing far more pressing issues like fires at Nubarashen landfill, lack of waste processing despite continuous promises, unchecked construction dust, and transport emissions). In the meantime, the PM ordered the creation of two new working groups to address the air pollution problem and the severe traffic congestion (he had previously ordered the tackling of this issue in 2022).

Image: Yerevan in smog in December 2024 (Source: Azniv Tadevosyan)

In this dystopian reality of apathy and distrust toward politicians, environmental crises, neoliberal economic policies that are hanging above the heads of the most vulnerable social groups, increasing cost of living and housing, it is nearly impossible to channel the concerns of citizens to the ruling party. Every criticism and concern is met with deflection, denial, lengthy explanations of why the responsibility does not lie with the ruling elite, or outright ignorance and personal insults. In a parallel universe, the PM actively posts TikToks where he goes about his day while listening to various songs and sending little hearts to his followers. His video, where he listens to a song by Zemfira, even went viral among Russian (mostly liberal) circles, many of whom could not even differentiate that Pashinyan was not the president, but the PM of Armenia. Seemingly innocent, this TikTok campaign might be aimed at winning the future votes of the Armenian youth.

For Pashinyan and his team, the electoral marathon ahead of the June 2026 parliamentary elections has been underway for some time, particularly following the significant opposition gains in the local elections in Gyumri and Parakar. The main tenet of this campaign is the “peace agenda” and the benefits that stem from a no-war situation. During Pashinyan’s rule, some economic indicators have improved, which may or may not be a result of government policies (although poverty remains high, along with the cost of living). Civil Contract is likely to capitalize on these economic growth indicators.

Another decision, made ahead of elections, was the reduction in mandatory military service. As of January 2026, the service will be cut from 24 to 18 months. Although positive in general, this reduction needs to be accompanied by more substantial structural changes, which do not appear to be taking place. Although the mandatory service has been reduced, the 25-day training camps for reservists aged 20-55 remain in operation. The Armenian society is generally reluctant to openly discuss issues related to the army, especially since people are aware of the shortages that the army is facing.

However, there have been a few reports of the ineffectiveness of the entire process, including multiple violations and the selective drafting of reservists. Effectively, the male population of Armenia is hostage to the state, which can cut them out from their daily life without proper consideration of their circumstances. There is very little discussion on how this affects households, especially vulnerable ones, and reservists who are either refugees or have already been through multiple wars. It is no surprise that there is a whole (and long-standing) tradition of draft evasion by way of emigration or changing one’s citizenship.

Image: Armenia-Azerbaijan border demarcation cutting through Kirants village (Source: Arshaluys Mgdesyan/DW)

There are two main interconnected issues that Pashinyan has been actively engaging in. First are the escalating clashes with the Armenian Apostolic Church. Everything started when Archbishop Bagrat Galstanyan led major anti-government protests (Tavush for the homeland), aimed against handing over four villages to Azerbaijan during a demarcation process, which gained momentum in May 2024. Galstanyan and several of his supporters have since been arrested with coup allegations. The government claimed the alleged coup involved clerics, oligarchs, and former military officers and was Kremlin-linked. Ever since, Pashinyan has led a media campaign against the church elites, aiming to “democratize” the Armenian Apostolic Church. While the church elites have never been popular with the Armenian public, these attacks on the Apostolic Church in general have not found mainstream support, turning simply into a political performance.

In parallel, the government has been after major oligarchs and opposition leaders, who they claim are affiliated with the clergy and backed by Russia. Two major arrests exemplify this trend. First, the business tycoon and philanthropist (or oligarch, depending on who you ask) Samvel Karapetyan was detained a day after making a statement in defense of the church. His house was raided, and Karapetyan was taken into custody with charges of calling for the usurpation of power. The second major arrest was that of the Gyumri city mayor, Vardan Ghukasyan (from the Communist Party of Armenia, which is practically inactive, very supportive of Kremlin narratives, and religious, too), who had long been under investigation for corruption (but not only), but was detained only months after taking office. Again, while there is no widespread support for these figures and perhaps even approval for their detention and investigation, concerns have been raised that the latter may have political motivations on behalf of the Pashinyan government.

There are increasing concerns over Armenia’s democratic backsliding. Since 2018, Armenia has experienced a persistent stream of leaked wiretapped recordings implicating officials, opposition actors, and clergy, exposing systemic gaps or misuse in the legal framework that is meant to tightly regulate surveillance. Amplified by pro-government media, these leaks have increasingly become instruments of political pressure and narrative control, normalizing the use of clandestine recordings to influence judicial processes, discredit opponents, and erode democratic norms around privacy, accountability, and institutional independence.

The “Peace Agenda,” the “Real Armenia,” and Karabakh Armenians

For the past months, Pashinyan and his team have been discussing and propagating what they call “The Ideology of the Real Armenia.” The latter is essentially a collection of Pashinyan’s (in)famous and perhaps tautological slogans like “The motherland is the state, if you love your motherland, strengthen your state,” “As the soul becomes a person with the body, so the nation becomes people through the state,” “There is a future, there is a future!”. The ideology aims to shift the focus from the idea of a “historic Armenia” to a “real,” contemporary Armenia: the existing internationally recognized Republic within its present borders.

The ideology is accompanied by a government decision on “Identification and support for the aesthetics of the Real Armenia”. As the cultural elites criticized the document, highlighting its repressive potential, Pashinyan’s most loyal cheerleaders, who retrospectively intellectualize and justify his brief announcements and decisions to the media, went on to praise the idea. They effectively pushed forward a narrative that Armenian culture has focused too much on suffering and delineating its identity vis-à-vis the neighbors; therefore, the proposal is to adopt a “critical” approach to Armenian culture. They propose to move away from the aesthetics of the past, where, in the absence of peace and the “policy of war,” the themes of sorrow and suffering have been predominant.

Pashinyan’s proposed ideology and the concept of “The Fourth Republic of Armenia” focus on reopening borders, reducing Armenia’s dependence on Russia, and normalizing relations with Azerbaijan and Turkey, which requires strong backing from Europe, the US, and regional partners. The homeland and the state should be viewed as one and the same. At first sight, obvious and sensible, this comes across as absurd against the backdrop of the 2023 ethnic cleansing in Nagorno Karabakh, which certainly is not a mere “historical” narrative of suffering, but a lived experience for 100,000+ refugees who have suffered war, blockade, starvation, and forced displacement. Neither is Armenia proper the “homeland” of these people who are indigenous to and have been living in Karabakh for many generations, cultivating its land, upholding their communities, and preserving its culture despite constant attempts at ethnic cleansing by Azerbaijan.

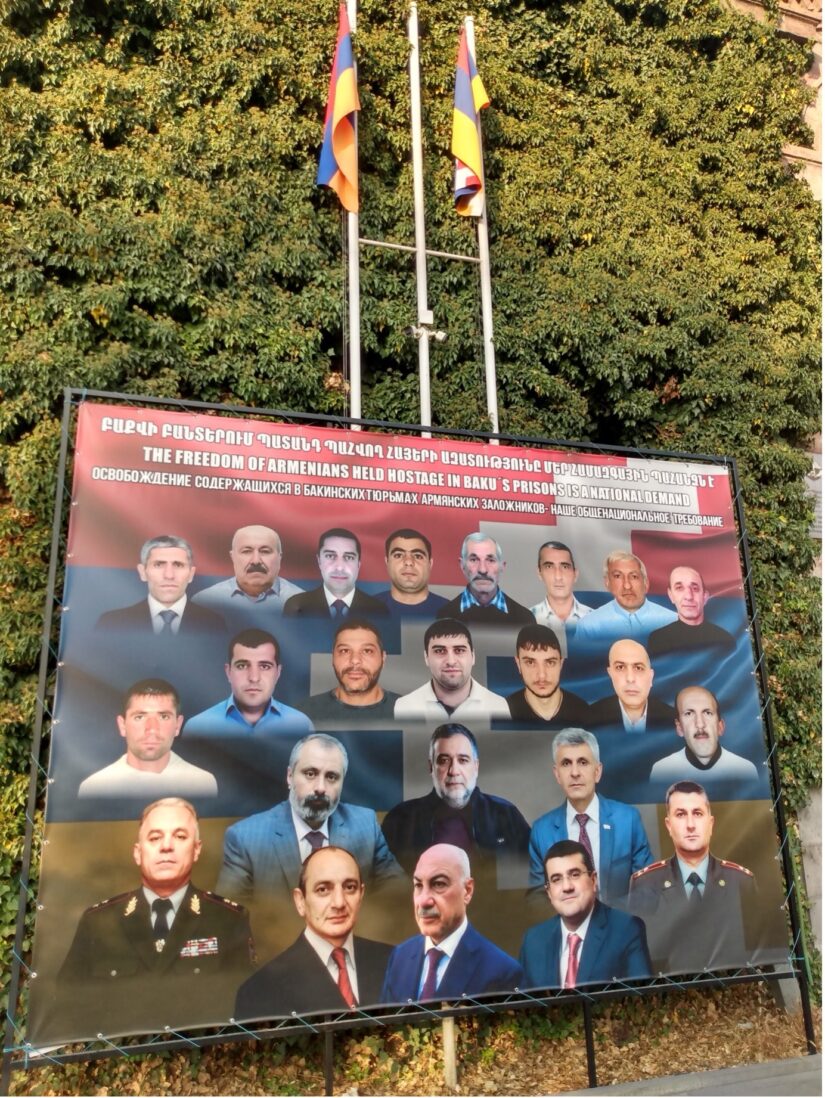

In the meantime, Aliyev’s long-standing international campaign of presenting Armenia proper as a disputed territory, or as he calls it, “Western Azerbaijan”, does not fall in intensity. Unsurprisingly, in November 2025, the leaked documents revealed that the campaign was orchestrated from the Presidential Administration to mobilize Azerbaijani public opinion and influence international perceptions of the region and the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict. Additionally, Azerbaijan continues staging sham “trials” of Armenian hostages that function not as judicial processes but as propaganda tools to vilify Armenians. State media coverage emphasizing alleged historical crimes by Armenians reinforces this narrative and distracts from the illegality of the detainees’ imprisonment. With the destruction of everything Armenian in Nagorno Karabakh, including cultural heritage, cemeteries, and homes, and in conditions where consistent hate speech and threats from Azerbaijan do not stop, Pashinyan’s proposed ideology and the peace agenda become just formalities without any substance or prospects of real reconciliation (which is not possible with Azerbaijan in its current political configuration).

Image: The only remaining billboard in Yerevan demanding the release of Karabakh Armenian officials from Baku prisons (Source: Eiki Berg)

Despite the peace agenda, Armenians still perceive Azerbaijan as an overwhelming threat (87% as of June 2025, according to the IRI report). This is no surprise, considering that even after the US-mediated agreement and Armenia’s steps back, Azerbaijan appears to have doubled down on militarization, significantly increasing its defense and security budget shortly after the Washington meeting. The peace discourse in Azerbaijan is practically banned, and every call for reconciliation is reinterpreted as “pro-Armenian.” The case of peace advocate Bahruz Samadov’s 15-year sentence on fabricated charges of treason serves as a testament to Aliyev’s hostility to the idea of peace itself. Even the recent mutual civil society visits show the superficiality of the “peace discourse”. Among the Azeri delegation visiting Yerevanwas the infamous “eco-activist” Dilara Efendiyeva, who was among the organizers of the blockade of the Lachin Corridor, which effectively was a state-orchestrated starvation of the Karabakh Armenians.

Another hostile step on behalf of Azerbaijan, which points to slim chances of peace, is that Aliyev abandoned the US-brokered TRIPP terminology as soon as he returned home, reviving the “Zangezur Corridor” narrative rooted in Azerbaijani. By strategically misinterpreting the connectivity project, which emphasizes respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the parties, as part of Baku’s longstanding territorial claims to Southern Armenia, it raises doubts about how willing Azerbaijan is to respect the TRIPP framework. While this raises the need for stronger US safeguards to prevent unilateral reinterpretation of such agreements and potential violations, given that Trump cannot for once get the names of both conflicting countries right, the prospects of compliance are rather precarious.

While it is possible to dismiss the entire ideology of “Real Armenia” as an attempt to divert public attention or simply an unimportant discussion, it is especially worrying in the context of the recent pre-signing of the peace agreement, according to which both sides are obliged to withdraw or settle any international legal claims between them, and to refrain from initiating new ones. That means that ongoing cases before institutions such as the ICJ, ECtHR, or PCA would need to be dropped, even without judicial conclusions (which do not preclude individual claims). I’m not even mentioning the question of the right to return, because the hostility of Azerbaijan toward Armenians is so intense that people do not even have an illusion that they will be allowed to ever return or have any security and dignity under Azeri rule if they do (which does not mean they do not have the right to struggle for that right). This simply means that Karabakh Armenians are stripped of every hope for collective justice in the near future. Pashinyan himself told NK Armenians to stop hoping for a return because these talks are “dangerous for the peace process,” effectively pushing the Karabakh Armenians to the margins of the Armenian public discourse.

Image: Five Years after the Second Karabakh War in Yerablur (Source: Narek Aleksanyan | hetq.am)

Despite the fact that Armenian society welcomed the Karabakh Armenians very caringly in 2023, there have since been anti-Karabakh sentiments growing among certain circles. Guess what? It was just one year after the ethnic cleansing in Nagorno Karabakh, when reports started to emerge on how the media outlets controlled or affiliated with the ruling party have been systematically targeting Karabakh Armenian refugees by spreading and legitimizing anti-Karabakh narratives and fueling negative sentiments toward Karabakh Armenians, whom they frame as particularly fond of Russia and the opposition demonstrations. The authorities and government-aligned media use refugees as scapegoats, painting them as outsiders who do not belong, are loyal to foreign powers, and are ungrateful. By so doing, the government shifts the blame for socioeconomic problems onto refugees and deflects the blame away from state policies.

As Karabakh Armenians had to flee within days, abandoning homes, possessions, livelihoods, and community networks, their life in Armenia has also been full of challenges. Apart from the international neglect, lack of accountability, severe psychological trauma, erosion of community and culture, and deep uncertainty about their future, they now have to deal with economic precarity, unemployment and labor market challenges, housing insecurity, among all else. The government stipends have been quite low and continue to decrease; the housing program requirements make it possible only for a small fraction of refugees to qualify. The Armenian government classified refugees as “persons under temporary protection,”effectively depriving them of automatic citizenship, thus causing concerns among refugees that obtaining Armenian citizenship could undermine their right of return, which partially explains the low rate of obtaining Armenian citizenship. This then results in political disillusionment with the Armenian government, which in its turn preemptively targets Karabakh Armenians, fearing the influence they might have in the internal politics.

The 2026 elections and political skirmishes

The government frames the upcoming elections as a struggle against corruption and foreign (read Russian) interference, both of which are issues the Armenian society is greatly concerned with. Although there are circles in Armenian society who believe in a closer alignment with Russia and thus fall prey to the fearmongering by oppositional forces, claiming that seeking less dependence on Russia will have catastrophic implications for Armenia, the majority believes in a balanced foreign policy that leans more towards the West while preserving pragmatic relationships with Russia. Increasingly, all involved parties are claiming that the Armenian elections will no longer bear a local character, instead gaining a geopolitical dimension and serving as a ground for the West vs. Russia competition.

The main power running for the elections is Pashinyan’s Civil Contract. They essentially hope to win the population with hasty “positive” policies. They are mainly running by juxtaposing themselves against the old regime in the face of politicians and the elites of the Armenian Apostolic Church, who, of course, they frame as pro-Russian. Using the same card as in 2021, albeit with greater force, Pashinyan hopes to capitalize on the Armenian people’s aversion toward the former presidents. The Civil Contract will likely capitalize on the “peace agenda” and improved relations with the EU.

They plan a constitutional referendum after re-election, and although they claim they have been planning this for a while, the public perceives this as another concession to Azerbaijan, which has continually pushed for the constitutional change as a precondition for the peace agreement, specifically to amend the preamble that refers to Nagorno Karabakh reunification. Pashinyan and his team are increasingly heavy-handed when it comes to their political opponents and even oppositional bloggers, so it remains to be seen which of the candidates will make it through to the elections. Additionally, the ruling party has been accused of abusing administrative resources, consolidating loyal media outlets, and coopting civil society and NGOs, many of whom readily serve as instruments of the state when the repression is targeted toward “others”.

The opposition is fragmented. The most vocal challenger of Pashinyan, as in 2021, is the former President Robert Kocharyan and the Armenia Alliance, the second-largest parliamentary faction associated with him. They blame Pashinyan for capitulation to Azerbaijan and advocate a return to closer ties with Russia. Kocharyan and his allies criticize Pashinyan for ceding Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding regions, also claiming that he is diplomatically naive if not incompetent. The same line is also held by the Kocharyan-backed Mother Armenia party. We do not yet know whether the other former President, Serzh Sargsyan, and the Republican Party of Armenia will be participating in the elections, despite their active involvement in public discourse. The affiliated With Honor parliamentary faction has launched an impeachment initiative against Pashinyan and criticizes him for rising repression, political arrests, and state overreach. Other old players are also being activated, although not yet with full force, including businessman/oligarch Gagik Tsarukyan (recently famous for building a 33-meter Jesus statue on mount Hatis) with Prosperous Armenia Party and the former security chief, Artur Vanetsyan, with his Hayrenik Party.

Image: Jesus Christ statue to be placed on Mount Hatis in the making (Source: Ani Gevorgyan | EVN Report)

New political actors are already emerging. One of the most important determining factors in the upcoming elections will be the question of who will fill the place of the third major power in the elections. One emerging power is the abovementioned Samvel Karapetyan and his Our Way party. They are likely affiliated with Russia, at least in terms of business interests. They seem to distance themselves from the former presidents, all while promoting their conservative views. Karapetyan’s nephew even gave an interview to Tucker Carlson, where he portrayed Pashinyan as a hater of Christianity. He went so far as to claim that the Armenian Genocide happened because Armenians are Christians and that Pashinyan’s main goal is to engage in genocide-denialism by undermining Christianity.

The other major competitor is the former Ombudsman Arman Tatoyan. He is perhaps the only candidate so far to have relevant education and experience for the post of the Prime Minister, which he makes sure to capitalize on. In a recent press conference, he asked the former presidents not to participate in elections since they are helping Pashinyan win. He frames himself as a proponent of close relations with the West (and the US in particular) but also a believer in a functional relationship with Russia. He is pragmatic regarding the peace process with Azerbaijan and claimed he has no illusion or aim of “bringing back Karabakh”. He also consistently brings up the human rights issues, such as the questions of POWs and captives.

From this picture, it becomes clear that none of Pashinyan’s political competitors are claiming a “reversal” in the Karabakh-related issues. Instead, the question becomes the foreign policy vector of Armenia and the implications it would have on the ability to maneuver during the negotiations. Russia has already fueled its disinformation campaignand started the dissemination of fake news in Armenia. Russian language Telegram channels have been activated in presenting the European Union as a destructive force and fearmongering about how the deterioration of relations with Russia will be catastrophic for Armenia. It is also expected that the EU involvement in the pre-election processes will increase, with something resembling the Moldova plan, and will likely work closely with the current government.

Armenia’s electoral system has become more transparent on election day; however, serious pre-election deficiencies threaten democratic integrity, including opaque campaign financing, misuse of state resources, politically biased observers, hybrid threats (both real and manipulated), and weakened civil society oversight. As civil society is experiencing a lack of funding and at times aligns with the state, it is essential that the EU supports initiatives to mitigate pre-election deficiencies without contributing to the current government’s efforts to manipulate public sentiments and fears. The government will surely continue to label every and any challenge as pro-Russian, in this way trying to neutralize its political opponents. While the Karabakh “leash” is now gone, there are many more that are simultaneously pulling Armenia in multiple different directions all at once.

Author: Azniv Tadevosyan