The System Worked: Somaliland’s 2024 Presidential and Political Party Elections

After the “great recession” of 2008 – 2010, Dan Drezner wrote a book called The System Worked which argued that, contrary to widespread pessimism and doubts, global governance performed far better than expected in responding to the worst global economic crisis since the Great Depression. Much the same can be said about Somaliland’s 2024 elections. After two years of delay and various electoral crises, the elections held on November 13, 2024, were generally peaceful, festive and orderly. More importantly, they resulted in a change in executive leadership and in the three political parties which will contest Somaliland’s politics for the next ten years. Specifically, the elections saw Abdirahman Mohamed Abdullahi ‘Irro’ of the opposition Waddani Party (Somaliland National Party) win the presidential election with 63.92% of the vote, defeating the incumbent President Muse Bihi Abdi of the Kulmiye Party (Peace, Unity and Development Party) who won 34.81% of the vote.

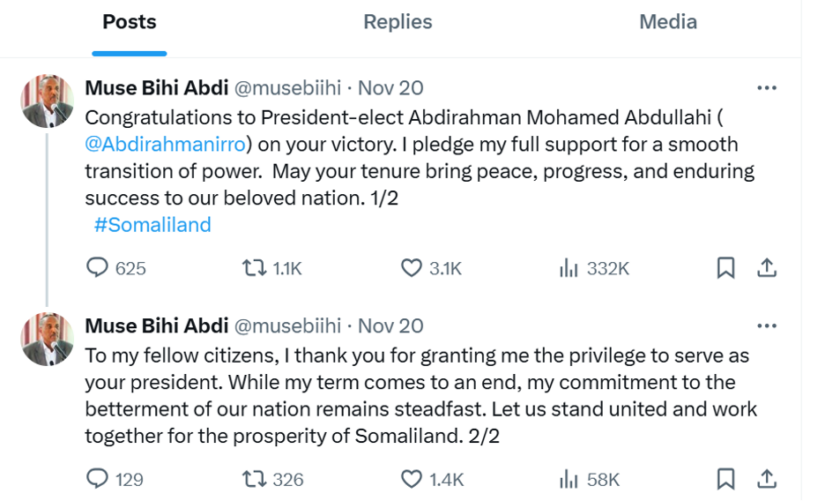

Image: Somaliland President Muse Bihi Abdi conceding defeat

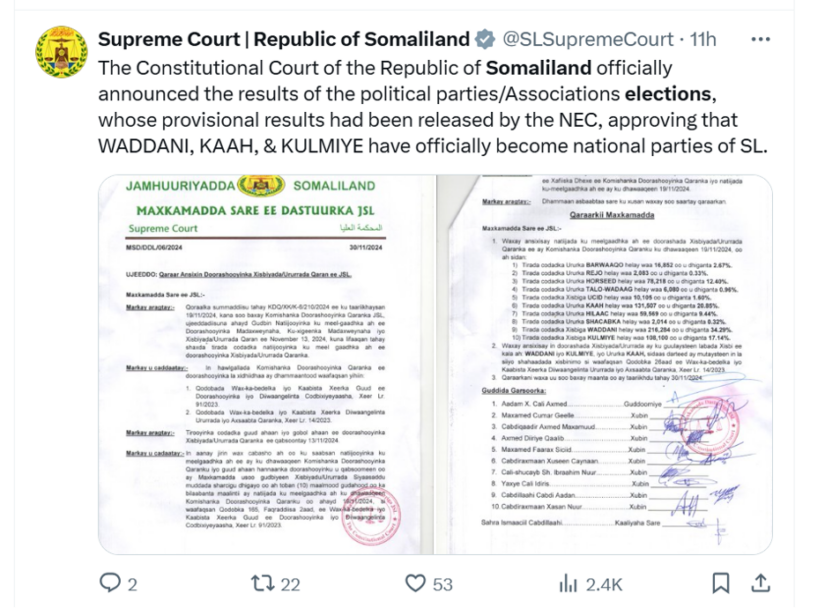

The simultaneously held political party elections also led to change with Waddani, KAAH (Alliance for Equity and Development) and Kulmiye emerging as the three constitutionally mandated political parties for the next ten years and UCID (For Justice and Development Party) losing that status.

Image: Triumphalist KAAH

Although it remains entirely unrecognized, Somaliland is not new to electoral democracy. It had a constitutional referendum in 2001 that was widely perceived as a referendum on its independence from Somalia. It has also held three previous direct presidential elections (2003, 2010, 2017), three previous local council elections (2002, 2012, 2021), two previous parliamentary elections (2005, 2021) and two previous political party elections (2002, 2012).

Somaliland’s 2024 combined presidential and political party elections directly stem from the unfinished business of its 2021 parliamentary and local council elections. Article Nine of Somaliland’s Constitution mandates the existence of precisely three political parties. While this restriction was originally designed to promote cross-clan alliances, it is increasingly criticized as being anti-democratic. Somaliland’s legal and established principle holds that those three parties should be open to competition from new entrants (“political associations”) in local council elections every 10 years (after two five-year terms). With the previous local elections having taken place in 2012, that 10-year mandate was due to expire in 2022, creating an incentive for the previous three political parties (Kulmiye, Waddani, UCID) to get the local council elections out of the way in 2021, in the hope that this would consolidate their status as parties for at least another five years until the next local level elections are due in 2026. Yet, this decision created serious problems for holding presidential elections originally due in 2022.

Somaliland faced a constitutional crisis in that President Bihi’s term was supposed to expire in December 2022 yet it had no parties currently holding a constitutional mandate to contest the election and no agreed process by which to establish that mandate. President Bihi’s preferred solution was the unprecedented mechanism of an election that solely decides which three associations win the right to operate as parties. The president’s plan was to hold that election before a subsequent presidential election. However, the opposition parties rejected that proposal, seeing it as a measure that would have made it possible for President Bihi to influence the establishment of new groupings before the existing opposition parties had the opportunity to contest the presidency. The opposition parties preferred presidential elections first and party elections after that.

Frustration with perceived electoral delays and the fear that the Guurti (upper house of parliament) would extend President Bihi’s term by two years resulted in in a series of protests in Hargeisa, Burco, and Erigavo that ultimately led to the deaths of at least five demonstrators on 11 August 2022 and helped spark a larger ongoing crisis centered around Las Anod in Somaliland’s east that has resulted in at least 150 dead, approximately 600 wounded, and 185,000 people displaced. Thus, in 2022, Somaliland faced dual and overlapping crises around Las Anod and its postponed presidential elections. While the Las Anod crisis remains unresolved, the electoral crisis was resolved when the three political parties agreed to hold the recently concluded simultaneous presidential and political party elections.

As it has done in past elections, Somaliland limited the length of the campaign and limited each political party or association to only campaigning on certain days of the week. This is largely done to preserve electoral peace as each party knows its allotted campaign days and does not disturb the other parties on their allotted days. In Somaliland’s major cities, this results in a kaleidoscope of different colors as one day everyone campaigning is dressed in orange (Waddani) while the next day everyone is in green and yellow (Kulmiye) or red (KAAH).

Perhaps the first blockbuster development in the election came before the official start of campaigning in August 2024 when Waddani and KAAH agreed to form a coalition to contest the elections. Among other things, KAAH agreed to support Waddani’s Irro in the presidential elections in return for cabinet roles if Irro won that election. Under the leadership of veteran politician and former cabinet minister Mohamoud Hashi Abdi, KAAH brought together several former members of parliament and high ranking officials, developed a broad base of support in Somaliland’s eastern regions and soon generated serious momentum in the campaign. Maybe the most dramatic moment of the campaign came just two days before the election when Abdirahman Abdillahi Ismail ‘Saylici,’ Somaliland’s vice-president since 2010 (who was term-limited from running again), announced that he was not voting for his boss, Muse Bihi Abdi and was instead switching his support to Irro.

According to Somaliland’s National Electoral Commission (NEC), 1,227,048 voters were registered for the 2024 elections. There were 2,637 polling stations across the country. These figures compare to 1,065,847 registered voters in the 2021 parliamentary and local council elections and 2,709 polling stations for those elections. The increase in voter registration can be explained by population growth in Somaliland. The decrease in the number of polling stations is at least partially attributable to the decision not to hold the elections in the four districts of Buhodle (Togdheer Province), and Hudun, Las Anod, and Taleh (Sool Province) in the eastern regions of Somaliland – thus disenfranchising voters there and further fraying their already weak ties to Somaliland. This also marks a significant reversal from the 2017 presidential election when voters in Hudun, Las Anod, and Taleh were able to participate.

As has been the case in recent elections, including two that I personally observed in 2017 and 2021, election day in Somaliland was largely peaceful and generally well-organized. A delegation of ambassadors and envoys from nine European countries plus the United States visited 30 polling stations in four different cities and congratulated “Somalilanders for exercising their right to vote peacefully and responsibly on 13 November 2024.” A mostly African-based group of international observers under the auspices of the Brenthurst Foundation also visited polling stations in four main cities. They “witnessed two notable security incidents” but concluded that the election was “free, fair and credible” and that there “were no serious incidents which threatened the integrity of the election on voting day.” The International Election Observation Mission (IEOM) sent 28 observers from 13 different countries who visited 146 polling stations in all six regions of Somaliland on election day. Their preliminary assessment found that “the elections took place in a mostly calm and peaceful environment where registered voters were able to exercise their right to vote during the day.” As it has done in past Somaliland elections, the IEOM highlighted numerous problems including limited pre-election voter information, a large number of seemingly underage voters, polling stations with steps that made access difficult for disabled people, polling stations closing for lunch or prayer times and problems upholding the secrecy of the vote.

One disappointing figure to note from the elections is that according to the NEC’s preliminary figures, the presidential election saw a turnout of approximately 55% of Somaliland’s registered voters while the political parties election saw a turnout of approximately 53% of registered voters.

While the three political parties’ Constitutional provision remains deeply unpopular and, in the view of many, fundamentally undemocratic, this was the second political party election that produced change in the composition of the three parties. The 2012 political party election saw the implosion of the formerly governing UDUB Party (United Peoples’ Democratic Party) and its replacement with Waddani as a new political party. The 2024 party election resultssaw UCID losing its status as one of the three political parties after securing just 1.58% of the vote and KAAH emerging as the now second largest party in Somaliland with 20.55% of the vote (Waddani won 33.8% and Kulmiye won 16.9% of the vote). Somaliland’s three-party system remains profoundly problematic, but the composition of the parties has at least been reshuffled. On 27 November, Somaliland’s Supreme Court officially certified the NEC’s election results, the final step in Somaliland’s electoral process.

Image: The Constitutional Court’s decision on approval of national parties of Somaliland

President-elect Irro’s margin of victory over incumbent President Bihi cannot be overstated and evokes former US President Barack Obama’s description of the 2010 US midterm election results as “a shellacking.” Irro secured more than 100,000 more votes in 2024 than Bihi did in 2017 (407,908 votes vs. 305,909 votes). His percentage margin of victory (29.11%) was more than double Bihi’s margin of victory in 2017 (14.37%). His margin of victory was also more than 100,000 votes greater than Bihi’s margin in 2017 (182,389 votes vs. 79,817 votes). Only a portion of these margins can be accounted for by the larger number of valid presidential votes (638,126 in 2024 vs. 555,142 in 2017) and the collapse in support for UCID presidential candidate Faisal Ali ‘Warabe’ (23,141 votes in 2017 vs. 4,699 votes in 2024).

What can explain Irro’s resounding victory? Cleary, the post-COVID years have not been favorable for incumbents. On one count, incumbents have lost 40 out of 54 elections in Western democracies since 2020. Examples of incumbents losing seats or losing office in 2024 include Botswana, France, Germany, India, Japan, South Africa, South Korea, the United States and the United Kingdom. The presidential election victory of the incumbent party in Mexico broke a string of 20 straight incumbent losses in Latin America. As is the case with voters elsewhere, Somaliland voters were clearly angry about inflation, high unemployment and a weak economy. President Bihi’s heavy-handed militarized approach to the crisis in Las Anod saw him lose support not just in the eastern regions but throughout Somaliland. Skepticism about the still secret provisions of Somaliland’s memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Ethiopia and doubts about whether Ethiopia will recognize Somaliland did not help Bihi’s cause either.

During the counting of votes, Somaliland lost its fourth president Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud ‘Silanyo’ who died of natural causes at the age of 86. President Bihi announced Silanyo’s death to the country and joined leaders from across Somaliland’s political spectrum at his state funeral a few days later.

Image: President Bihi quickly and graciously conceded defeat and accepted the results of the election.

President Bihi pledged his full support for a smooth transition of power. Under Somaliland’s Constitution, Irro will become president on December 13, 2024, one month after the election. Shortly after the election, President Bihi hosted President-Elect Irro at Somaliland’s Presidential Palace. Irro praised Bihi for graciously accepting defeat and for his integrity throughout the election process. NEC Commissioner Musa Hassan also thanked President Bihi “who never demurred of a commission request submitted to him” and noted that the Somaliland government funded nearly 75% of the total costs of the elections with other funding from the European Union, Taiwan and the United Kingdom.

Image: Outgoing President Bihi meeting with President-elect Irro

In contrast to Mozambique where a disputed election has led to a violent post-election crisis, Somaliland joins a growing list of sub-Saharan African countries including Botswana, Liberia, Mauritius and Senegal where presidents and prime ministers have gracefully conceded electoral defeats and worked to ensure smooth transitions of powers. Yet, as noted after its 2017 presidential elections, Somaliland’s democracy still “juxtaposes striking successes with recurrent and persistent problems.” Somaliland has now seen five presidents leave office peacefully. It has twice elected opposition-controlled parliaments and it has now changed the mix of its three political parties on two different occasions. Yet, as the NEC notes, “Of the several major setbacks and shortcomings of the democratic process, one of the most serious and intractable is repeated election delays, in which extensions are granted to the term periods of Somaliland’s representative institutions.” Presidential elections which are supposed to take place every five years have averaged every seven years (2003, 2010, 2017, 2024). There was a 16-year gap between supposedly five-year parliamentary terms (2005, 2021) Local council elections average 9.5 years (2002, 2012, 2021) when they are supposed to occur every five years. One of the first challenges for the incoming Irro Administration will be to keep parliamentary and local council elections due in 2026 on track. Given the emergence of KAAH as a new political party and the disappearance of UCID, there should be a special urgency in avoiding unnecessary delays to these elections.

Irro faces several major challenges going forward. Perhaps the biggest is trying to resolve the Las Anod crisis. He has pledged to pursue peaceful negotiations and abjure military solutions. While this is welcome, this is a complicated crisis with long-standing roots that will not be easy to resolve. Reducing inflation and widespread unemployment will also be challenging for an economy heavily dependent on livestock production in a drought-prone region. Irro has also suggested caution on the Somaliland-Ethiopia MOU. His advisers have rightly pointed out that it is hard to take a definitive position on a document they have not yet seen, but they will be tasked with moving forward on this MOU or trying to renegotiate it shortly. One hopeful sign is that Kenya and Uganda have offered to mediate the dispute between Ethiopia and Somalia over this MOU but whether that intervention will be successful or not remains to be seen.

Somaliland’s partnership with Taiwan appears robust. Taiwan has pledged strong cooperation with the incoming Irro Administration and it has backed this up with major investments in a new road from Hargeisa’s airport into the city and a major new hospital facility in Hargeisa. The new Somaliland administration also has high hopes for improved relations with the incoming Trump Administration in the US. Significantly, a strong delegation of US officials are expected to attend Irro’s inauguration which has not previously been the case. Somaliland’s recognition was also advocated in the Heritage Foundation’s (in)famous Project 2025 report which specifically calls for “the recognition of Somaliland statehood as a hedge against the U.S.’s deteriorating position in Djibouti.” The Irro Administration faces the delicate task of building upon its predecessor’s progress in improving relations with the US and Taiwan while avoiding what Brendon Cannon has characterized as “Kulmiye’s complete reliance on the West.” Irro hopes to broaden relations with other African and Global South states. Somalilanders remain fundamentally committed to the goal of widespread recognition of their proclaimed sovereign statehood, but that goal has entirely eluded them for the past 33 years. While another peaceful transfer of power should help promote their cause, Somaliland’s case for “earned sovereignty” has so far fallen on deaf ears.

Author: Scott Pegg