Roundtable on “Entangled Borderlands” at Tartu Conference, 11-13 June 2025

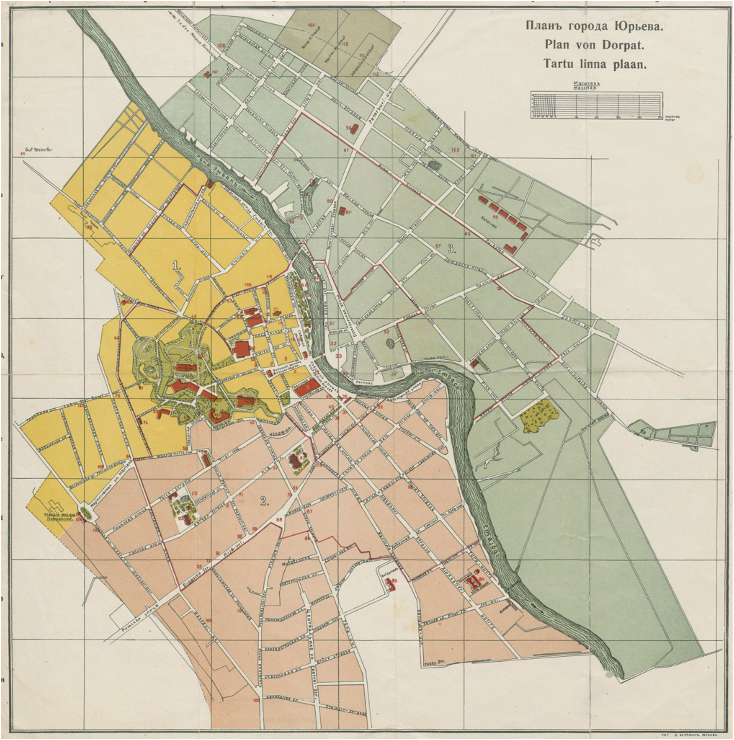

On 13 June, three members of the project – Catherine Gibson, Janet Laidla, and Julia Malitska, together with Teele Saar – organised a roundtable at the Ninth Annual Tartu Conference on East European and Eurasian Studies on “Entangled Borderlands: Intra-Imperial Mobilities in the Late Romanov Empire.”

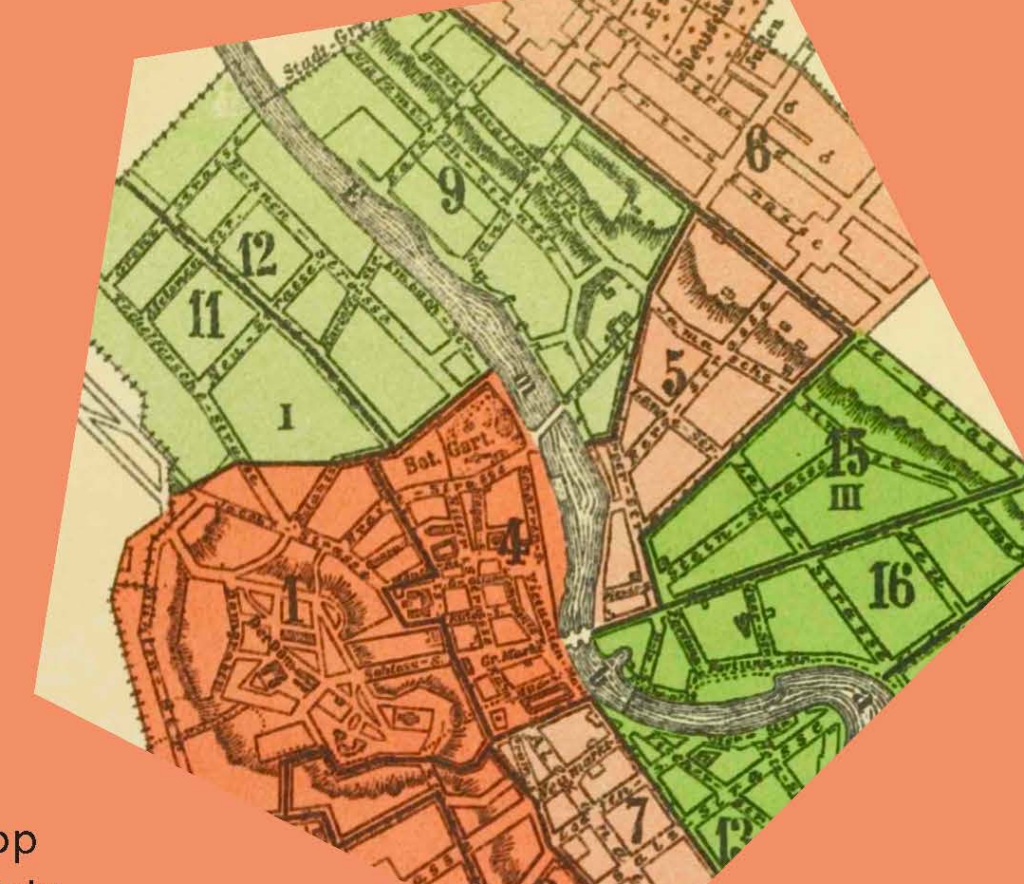

The roundtable aimed to explore how, at the turn of the twentieth century, the Romanov Empire facilitated opportunities for the mobility of individuals and ideas between different imperial regions. While scholarship has mostly examined mobility in terms of relations between non-Russian borderlands and the empire’s metropole, far less attention has been paid to trajectories connecting the empire’s border regions. This roundtable brought together scholars working on women students who travelled to take exams at the University of Tartu, the transfers of ideas and practices among life-reform activists, and the mobility and actual movement practices of the steamship passengers in Baltic Provinces and Finland, to reflect on how studying these intra-imperial mobilities might generate new perspectives on the history of Eastern Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Here are some reflections from Julia, who shared her research on the spatial entanglements of vegetarian activists in the western borderlands of the empire:

I argued for the need to abandon a metropole-centered perspective in order to untangle the complexity of vegetarianism as a form of life-reform activism. Contrary to the historiographic portrayal of vegetarianism in the Romanov Empire as being strongly associated with Tolstoyism, in practice it was a polycentric (with multiple spatial hubs) and heterogeneous phenomenon (marked by ideational diversity), shaped by multiple imperial contexts. My focus is not on the involuntary abstention from meat driven by religious practices such as Orthodox fasting, but rather on vegetarianism as a conscious and deliberate rejection of meat in the human diet motivated by a variety of reasons ranging from ethics, morals to health and hygiene. I interpret it as both a corollary and a critique of modernity, as well as a countercultural reaction by urban dwellers of the Romanov Empire to the global meatification of human diets at the turn of the 20th century. Vegetarian activism, it turns out, developed as a form of horizontal reformism, with ideas and practices spreading through peer-to-peer interactions and largely enabled by the rise of print media, along with the expanding postal system and railway network.