Data Search

Data Search

Where and how to search open data depends very much on the users, their research areas and information needs. Data search is based on the standard metadata published by the researcher.

Similar to searching in article databases, data registers can be searched by the author, title and keywords.

Besides these bibliographical metadata, the type of the data is also very important:

The astronomer needs long-term observation data, which is stored directly from the instruments in a disciplinary repository; the data is dynamic and large-scale.

Developers of artificial intelligence need big data for machine learning.

In medicine, for example, medical imaging files and 3D images are needed, not to mention the patients’ health data.

In archeology, field diaries, photographs, artifacts are of interest.

Social scientists are interested in questionnaires, survey data, interviews and video materials.

In the humanities, research is often based on previously published publications and manuscripts.

Usually, several different types of data are collected in one and the same research project. For example, when studying hurricanes, the data types include videos, images, location data, tables with measurement results, etc.

Metadata

Metadata is data about data.

Metadata provide context and provenance for research data.

There are different types of metadata, but for search, the descriptive bibliographical metadata mentioned above prove to be the most important:

- author

- title

- keywords

- year of publication.

Once a database of interest has been identified on the basis of these characteristics, technical metadata should be considered:

- data types

- file sizes

- how the files are organized

- whether there are encrypted files

- what software has been used

Administrative metadata provides information on how the database can be re-used:

- project and responsible executors

- who is the owner of the data

- licenses

- access restrictions

- embargo period

- contacts

Each database is accompanied by a text file, README.txt, which describes the database in natural language. In many ways, this file repeats metadata, but goes deeper into the data descriptions with the aim of making the database understandable to other researchers. It may explain the principles of naming the files, the file structure, encodings, and special file formats.

The README.txt file also refers to the research methods, the hardware and software, and the instruments and their specifications used, to make it possible to reproduce the research.

The long-term storage and data sharing is described in more detail, especially if the data cannot be shared for some reason or access has been restricted.

The file should list all the standards used (data standards, metadata standards, security standards, etc.).

Metadata can be used to determine whether FAIR data is human-readable and machine-readable at the same time.

Equipped with such information, it is possible to decide whether the database can be useful and only then to start downloading the data.

Metadata standards

Metadata is the structured machine-readable information; such information is easy to standardize and process on a computer, which is the basis of how a search engine works. The more metadata describes the dataset, the easier it is to find and understand the dataset.

Due to the fact that data from different research fields are very different, different characteristics are also needed to describe them.

Let us take, for example, phonetic research. The data include audio recordings of a speaker of a specific language, which can later be explored from many aspects. In addition to subject metadata (language, dialect), the metadata could also include:

- information about the speaker (gender, age, place of residence, origin, social status, state of health)

- information about recording conditions (weather, background noise, distractions)

- technical information (storage devices, software, quality indicators)

Based on this metadata, for example, an ethnologist can decide that this data is also useful in ethnology research.

Such domain-specific features are collected and structured in professional metadata standards.

A metadata standard is a requirement which is intended to establish a common understanding of the data.

Many registers allow you to limit search results to a metadata standard, so it’s a good idea to be aware of the metadata standards in your field.

Some examples of metadata standards:

DDI – Data Documentation Initiative: standard for social sciences and economics

SPASE Data Model: astrophysics

MIAME standard: DNA microchip-technology

MIDAS-Heritage: standard of cultural heritage objects (buildings, sites, shipwrecks, parks, gardens, artifacts).

In addition to subject-specific standards, more general standards have been developed to meet the needs of a very large number of users.

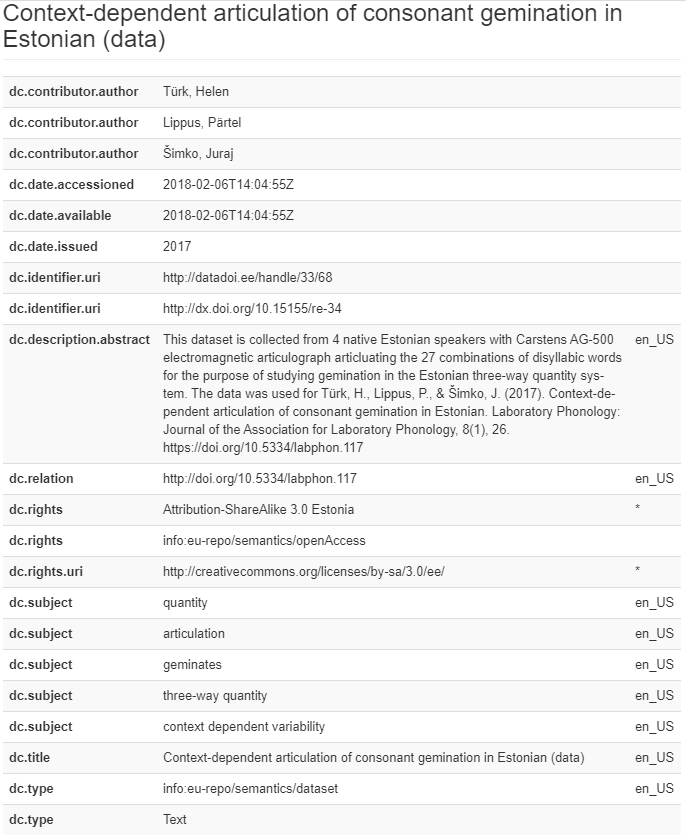

Probably the best known of these is the Dublin Core standard, which is easy to understand and implement in information systems. The Dublin Core standard is also used by the data repository DataDOI managed by the UT library; for example, see the metadata of a dataset:http://dx.doi.org/10.15155/re-34

Where to find data

First of all, you should think about where and how to look for data, and plan a strategy. There are several ways to access research data, you need to be able to recognize and use these possibilities. In general, the data is storaged in data repositories and we look at them in the next section. Besides searching data repositories and data registers, information about data availability can be found in academic journals.

Information about data in an article

As many research funders and publishers require that the underlying data of an article should be published together with the article, it is the easiest way to find out whether the article and data are linked. A persistent identifier for the article and data, leading directly to the data, is used for linking.

The data, methods and code can be found in the article as supplemental material or supporting information, or explicitly in the Data and code availability section.

Some academic publishers require a Data Availability Statement (DAS) with the article, such as required by the Taylor & Francis publishers: A data availability statement (also sometimes called a ’data access statement’) about the data associated with a paper specifies conditions under which the data can be accessed. They also include links (where applicable) to the dataset.

An example of linked data from PLoS ONE: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230416

|

|

Data journals

Data journals publish peer-reviewed data articles, i.e. articles about data but not the results of data analysis. This type of an article gives the researcher the opportunity to describe their dataset in more detail, for example to explain the methods of data collection. The data article is certainly of great benefit to researchers who would like to reuse the data, but also to the researcher who published the data article, as the number of citations increases.

There are several disciplinary data journals, such as:

Nature Scientific Data

Biodiversity Data Journal

Research Data Journal for the Humanities and Social Sciences

Journal of Open Archaeology Data (JOAD)

Journal of Open Health Data

Data repositories and data registres: see next sections

Successful data search

If the data search has led to datasets of interest, these must be thoroughly studied and their quality and reusability assessed.

The README.txt file and all metadata offer much help. If we start to delve into them, we can find many good but also bad examples.

Metadata should provide sufficient information so that you would download a dataset only when you are absolutely sure that you want to explore or reuse it.

The following article provides some tips for effective data retrieval:

Gregory K, Khalsa SJ, Michener WK, Psomopoulos FE, de Waard A, Wu M (2018) Eleven quick tips for finding research data. PLoS Comput Biol 14(4): e1006038. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006038

- Tip 1: Think about the data you need and why you need them.

- Tip 2: Select the most appropriate resource.

- Tip 3: Construct your query strategically.

- Tip 4: Make the repository work for you.

- Tip 5: Refine your search.

- Tip 6: Assess data relevance and fitness-for-use.

- Tip 7: Save your search and data-source details.

- Tip 8: Look for data services, not just data.

- Tip 9: Monitor the latest data.

- Tip 10: Treat sensitive data responsibly.

- Tip 11: Give back (cite and share data).